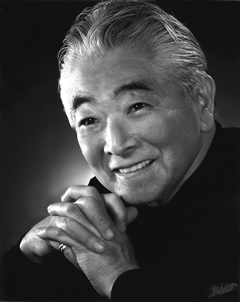

This past April, architect Raymond Moriyama (BArch 1954) received the Sakura Award for contributions to Japanese culture in Canada and abroad. Moriyama – who designed the Canadian Embassy in Tokyo, the Ontario Science Centre and the Canadian War Museum (at the age of 70) – delivered a speech at the Sakura Ball. He spoke of his life’s challenges – from being severely burned as a child when he accidentally upset a pot of stew, to being sent to an internment camp (the fate of 22,000 Japanese-Canadians after the bombing of Pearl Harbor) in Slocan, B.C. Below is an excerpt.

War is hell. Physically facing an enemy is hell. It is a psychological hell when your own country, the country of your birth, stamps you an “enemy alien,” disowns you and expels you to an internment camp in the mountains far away from home.

Father was sent to a POW camp in Ontario for resisting the government’s contradictory action of going to war to preserve democracy and individual rights while, at home, disregarding the rights of 22,000 citizens. Mother, who was pregnant, in despair and having to face a future with three children and $34.92 in savings after 13 years of struggle in Canada, lost the baby: the only brother I could have had. In the B.C. camp, I was mocked in the public bath by fellow Japanese-Canadians calling my scars [from childhood burns] a contagious disease.

I was disowned by my country and mocked by my own community. My father was a POW in faraway Ontario, and my self-esteem was destroyed. In despair, I decided to bathe in the Slocan River on the other side of a little mountain away from the camp. The water was glacial, but it was better than hot tears. To see who might be coming, I built an observation platform. Soon I found myself wanting to build my first architectural project, a tree house, without being found out by the RCMP. I used just an axe as a hammer, an old borrowed saw, six spikes, some nails, a rope, and mostly branches and scraps from the lumberyard. It was hard work building it by myself, and it was a lesson in economy of material and means.

That tree house, when finished, was beautiful. It was my university, my place of solace, a place to think and learn. This is when I first learned to listen to the Earth. The view, and sound, of nature from the tree house was astonishing: the mountains green and silver; the sunrise, the sunset; the whisper of the river and the sound of the wind. I was learning the true meaning of dynamic permanence of temporariness – that the “frightening” storm was a part of a balance to the beautiful sunset and that it was less vengeful than man’s irrational thoughts and deeds.

I was amazed that my despair was subsiding. I began to understand that I could not hate my community and my country, or my hate could crush my own heart and imagination. I replaced the despair with ideas about what I could do as an architect to help my community and Canada. The inspiration for the Canadian War Museum came during this period, at age 12 and 13: the sound of nature and the evening breeze I heard in the tree house coming fully alive 60 years later. The Canadian Embassy in Tokyo is a tree house inspired by the original.

My high school graduation came soon after the war, so my father had very little money. Instead of a material gift, he passed me an envelope at the graduation ceremony. For a moment, I thought it could be a cheque to pay for my tuition at U of T. But it was better than that or anything else he could have given me. It was a poem he worked on very hard, I’m sure, with a lot of love and wisdom. It was beautifully scripted, and it read: Into God’s temple of eternity, drive a nail of gold.

He did not ask me to build the temple. He wasn’t even asking me to design it. He was asking me to drive in just one nail – just one, but one forged of gold. This poem propelled and sustained me through university and my professional life. I thought about it for years and tried to live up to its fuller meaning.

I realized architecture needed to be more than nicely proportioned surface treatment. If it is to be truly “golden,” architecture has to be humane and its intent the pursuit of true ideals, of true democracy, of equality and of inclusion of all people.

Recent Posts

U of T’s 197th Birthday Quiz

Test your knowledge of all things U of T in honour of the university’s 197th anniversary on March 15!

Are Cold Plunges Good for You?

Research suggests they are, in three ways

Work Has Changed. So Have the Qualities of Good Leadership

Rapid shifts in everything from technology to employee expectations are pressuring leaders to constantly adapt