It was the sort of day you appreciate at the end of the Ontario summer: sunny, hot, but with a nippy wind hinting at the cold weather to come. Architect Margaret Russocki and her husband, Stan, one of Toronto’s top commercial realtors, looked out over Six Mile Lake from the dock of a cottage they’d recently purchased here, just east of Georgian Bay. Stan said he wanted to make the most of one of the last good days by going out windsurfing, and his wife at once said she’d join him. A tall, athletic woman, Margaret (BArch 1973) was not one to be left on the dock.

“I got out first, and, when she came out, I told her ‘Don’t let the wind push you down that way,’” he says. ‘The way the wind is, you’ll get stuck there.’”

She shot back: “I know what I’m doing.”

Stan returned to the cottage to use the washroom and when he came back out he saw her board across the bay, exactly where he’d warned not to go. Something was wrong: she was in the water, slumped over her board. He called out to her, but, getting no response, dove in and swam quickly to her – she was not conscious. He dragged her to the shore in front of a neighbour’s cottage, and tried to get her breathing again through mouth-to-mouth.

It was no use. An ambulance sped them to a hospital in Parry Sound, and the doctors soon confirmed what he already knew: She was gone. A leaky heart valve had burst. Their kids were away at the time, their daughter Ania and son Martin, on a trip to Mexico and Spain – Stan made plans to meet them at the airport to break the news.

Margaret Russocki was 44 when she died, on Labour Day, Sept. 2, 1991. She had already made a strong showing in her chosen field, founding and running a busy Toronto architectural practice, with a partner, Marek Zawadzki (BArch 1974). In her too-short span, she managed to complete projects valued, in total, at more than $200 million – a respectable aggregate amount for any practitioner, and reportedly the most built by a Canadian woman to that date.

Her work ranged widely from a library to a fire hall, from bank branches (five) to malls (five conversions) – to her specialty, schools (21 in all). Her schools and mixed-use community centres often aimed to provide focal hubs for the rapidly growing suburbs around Toronto – and some won awards for their innovative, adaptable designs.

Margaret Russocki was many things. She was an immigrant who sweated to master the language and customs of a new country, a woman who started late in a male-dominated profession, after becoming a wife and mother, but managed to thrive in it. An unusual combination of dreamy artist and savvy businesswoman, she was a person whose ways – whose colour – rubbed off on others, leaving a mark that was, that remains indelible.

“Her death just didn’t seem possible,” recalls Luigi Ferrara, a young architect working for her at the time – who is now dean of George Brown’s architecture program. “This driven and ambitious woman. She was just breaking through, from the schools and community centres she’d done to bigger things.”

***

It is fitting for such an active couple that they met skiing in Poland’s Tatra Mountains, when he was 19 and she was 16. Both were avid skiers, city kids, him from ancient Krakow, her from Warsaw, the war-ravaged capital. Her parents, both professionals, were careful and loving.

The Communist regime was the only one the two youngsters had ever known, but he’d heard stories of a better life abroad, and, during his university years, hitchhiked across Western Europe. In letters, Stan encouraged her also to take to the road, and, after three years of architecture school in her home city, Margaret hitched a lift to Paris with a French film crew – they’d come to Poland to shoot French president Charles de Gaulle’s state visit there.

“She won people over,” says Stan. “You wanted her along for the ride.”

The pair reunited in Paris in heady 1967, a city roiled by student activism. Through someone he’d met in his knocking-about, Margaret landed a contract at an important architect’s office. Alexis Josic, like many in his generation, was inspired by Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier’s major public projects. Josic and the trendy Team Ten, with whom he was associated, took the modernist master’s sculptural, concrete-based work to a new, slightly more playful place, puncturing, for instance, vast slab surfaces with little, irregularly situated balconies.

Architect Ferrara sees these beginnings in Margaret’s later work, which also often makes copious use of concrete and has curves and shapes that rebel against the rectilinear grid. But her husband balks at the idea that her buildings spring primarily from this canonical source. “She wanted above all to give pleasure to a building’s users, whose needs she learned about.” Still, there are traces of the French modernist aesthetic in her pieces.

A restless soul, Stan accepted an invitation to come to Toronto from his Polish emigré uncle. Against her family’s advice, Margaret soon followed him over. “In a tough phone call,” he remembers, “her parents made me promise that I would make sure she finished the architecture studies she’d started. She got pregnant, we married, life started to gallop along.”

Stan landed a job in realty at the brokerage A.E. Lepage (before its merger with Royal Trust), and took urban studies at U of T (BA 1973 Innis). Margaret completed her studies at the university’s Faculty of Architecture, a degree she started when pregnant with their second child, Martin. (They managed all this, he says, with the help of a series of nanny-housekeepers from Poland.)

The architectural program wasn’t exactly female-friendly at the time, contemporaries say. Another woman student told a Globe and Mail reporter: “Boys in the class can’t really accept you. They pretend you’re not there.”

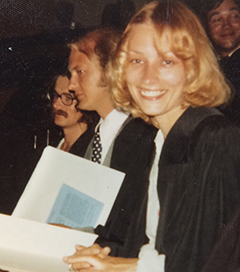

Still, with her work ethic and prodigious drafting abilities, the young mother of, by then, two children managed to finish top in her graduating year, 1973. She was one of only two women in her class of 22.

At around the time she joined the workforce, the Globe reported that just over 60 of the 3,330 registered architects in the province were women – about two per cent, as compared to about 25 per cent now. And she struggled hard to find her way, doing some small residential work out of an office in their home’s basement, working a stint at the then up-and-coming Jack Diamond’s office. “She was a thoughtful, intuitive designer,” says Diamond, the architect who went on to contribute the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts and the Metro Central YMCA to Toronto’s cityscape. “She had a strong personality and a great hand.”

Still, U of T’s top graduate couldn’t land a permanent job at any of the city’s established practices. She ended up taking an in-house job as a designer at Bell Canada, something considered a second-tier post at the time. But she threw herself into it, and told others later she learned much about corporate decision-making and developed a network of strong consultants and engineers whom she’d use when she struck out on her own.

Her big break came when the Russockis heard that a suburban Catholic school board was looking for an architect. She landed the meeting, presented her credentials and followed her salesman husband’s advice on the pitch – “Get their attention, maybe use your pencil once or twice to show your drafting skills, and then shut up and listen to them.” The job was hers: a contract to build St. Patrick’s Elementary in Markham, reportedly the first big school project completed by a woman – done in 1984.

At the time, several people advised her it would help if she had a male partner, both with the (mainly male) clients and the (also mainly male) contractors on the work sites. Zawadzki was someone she knew and trusted, another member of the growing Polish-Canadian community. He also had experience doing big public projects. Colleagues who knew them both say he was the careful yin to her flamboyant yang, and the two both benefited from the alliance.

“It was a good time for us, the suburbs were growing, school boards and municipalities needed a lot of facilities,” Zawadzki says. They were a small firm of immigrants going up against bigger, older outfits, many headed by principals with English and Scottish surnames – not names, he says, that ended in the telling ‘cki,’ ‘zki,’ or ‘ski.’

Even so, they won their fair share of work and Russocki, he says, was good at landing it, despite frequent attacks of nerves before the pitch meetings. “She was never confident of her English,” says their first hire, Ella Mamiche, now a partner at the firm. “She practised the presentations hundreds of times, with me as her audience.”

After a few years, the completed projects, especially the schools, started to speak for themselves. In all, she and her team designed 14 elementary schools and seven high schools in the go-go decade before her death. Scarborough’s Milliken neighborhood was growing at such a pace in the ’70s and ’80s, that its Catholic elementary school students studied in 11 portable classrooms. Completed in 1988, the Prince of Peace Catholic School that her team built to replace that ragtag assemblage, offered a two-storey atrium for all-school meetings, and won Scarborough’s top design award that year – one of three schools that Margaret designed to win municipal awards over the years.

In a way that is typical of the period’s postmodern style, the school amalgamates different geometrical forms: two solid, rectangular masses stand guard on either side of the entry; over it, a glass cover against the weather comes to an equilateral triangle at its front; and, in the school’s signature design move, there’s a vast-curved wall at one end.

“The budget was tight, it always was,” Mamiche says. “And I learned that she would rather have one big signature gesture – that curve – rather than lots of little ones.”

“Her buildings were not traditional,” Ferrara says, “but they were comfortable.”

Margaret also combined simple shapes – triangles and circles departing from strong horizontal lines – in a Scarborough complex that includes both the Mary Ward Catholic Secondary School and L’Amoureux Community Recreational Centre. Opened just after her death and situated next to an often reflective pond in L’Amoureux Park, the building serves both the local community and the school’s 1,200 students, with shared gym and outdoor spaces. This arrangement enabled funds to come from different agencies, and provided a centre of gravity to a speedily built bedroom community that didn’t have many then.

Pat Marum, then a trustee on the Metro Separate School Board, praised Russocki for helping to manage an unwieldy consultation process, getting input on the design from the school’s staff, students and parents and the community at large. With so many stakeholders, Marum says, “A very delicate line needed to be walked … Margaret was sensitive to their needs.”

Margaret helped design another such complex, Etobicoke’s Humberwood Centre, a facility completed, with significant amendments, after her death. It combined two rarely combined entities, both a Catholic and a public school, as well as a library, daycare and recreation centre.

These types of multi-use buildings were new at the time, but Margaret’s son Martin – who earned a bachelor of architecture from U of T in 1998, and is now an artist and game designer in New York – also sees something old in them: “The important buildings of Polish towns were often gathered around medieval squares.”

The buildings are memorable, with some panache to them – as was the personality that produced them. Her children remember her arriving, in a big fur coat, by helicopter midway through a ski vacation they were taking in Whistler. The road from Vancouver was blocked and she didn’t want to miss any more of the family vacation. Her daughter pictures her always speaking on the period’s brick-sized car phone, wearing bold ’80s fashions, as she darted around the city in her beloved Saab. Her husband remembers her calling for help from the road once because she, focused on other things, had forgotten to put both gas and oil in it.

Margaret also left behind a firm that was a going concern, and which has grown, under Zawadzki’s leadership, to employ more than 60 architects, working out of offices in Toronto, Vancouver and Dubai. “We didn’t lose any clients after Margaret’s death,” he says of the firm. “We felt an obligation to continue in her spirit.”

Zawadzki is proud that the firm, now named ZAS Architects, has always had roughly equal numbers of women and men practitioners working there, as well as a cosmopolitan mix on staff. “At one point, we had people from 21 different nationalities here.”

Mamiche, now a senior partner, gives me a tour of the busy Toronto office, and says Russocki did lodge something intangible here, passing on her exacting standards, as well as her high-spirited ability to mix business with pleasure. Weather permitting, she would hold debriefs after big pitches, Mamiche says, around her home’s pool. She shows me photos of raucous-looking office parties past, and recalls the time when a police officer came to the office on Russocki’s birthday to bust her for her numerous parking tickets, or so he said. “When the music started playing,” Mamiche says, “Margaret realized he was not a real cop.”

But Mamiche then gets serious. “I also came from Poland, from Gdansk. She gave me my first shot. She was my mentor, and I wanted to be her. I learned so much. It sometimes drives my colleagues crazy, but if I see a project isn’t there, even at the last minute, I’ll push, like she would, to make changes.”

Russocki’s son, Martin, says he still has dreams in which she appears. “It’s a happy night when she comes.”

For daughter Ania, who, until recently, served as the executive director of brand marketing at U of T, says working at the university reminded her of her mother, lost to her too soon. “Some of our early family photos have University College in the background, or were taken with models she built while she was a student here. It feels … good, that connection.”

At the end of our interview, Stan uses a valedictory metaphor to sum up his late wife: “She was a joyous motorboat. She looked forward, not back at what she’d lost or left behind. She also didn’t worry so much about the wake she caused.” He chuckles, “Sometimes that wake was big.”

Alec Scott graduated from the Faculty of Law in 1994.

Recent Posts

For Greener Buildings, We Need to Rethink How We Construct Them

To meet its pledge to be carbon neutral by 2050, Canada needs to cut emissions from the construction industry. Architecture prof Kelly Doran has ideas

U of T’s 197th Birthday Quiz

Test your knowledge of all things U of T in honour of the university’s 197th anniversary on March 15!

Are Cold Plunges Good for You?

Research suggests they are, in three ways