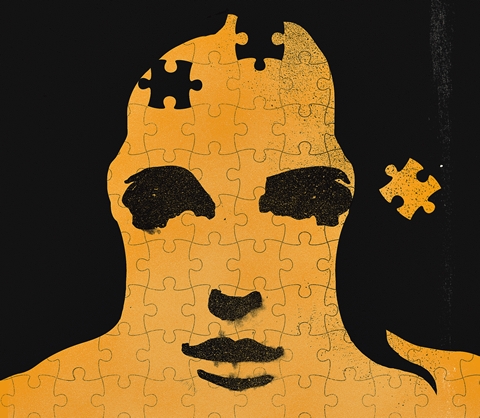

Theories of human psychology influence not only how we treat mental illness, but how we understand ourselves. The ancient Greek notion of the four humours remains with us in our idea of sanguine or phlegmatic personalities. Freud’s ideas gave us unconscious motivations, egomaniacs, narcissists and more.

These days, if you know someone who’s suffered from major depression, or think you may have social anxiety disorder, or know a child with attention deficit disorder, you’ve been influenced by a more modern psychological viewpoint – one put forth by the American Psychiatric Association in its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), which describes all recognized mental disorders. Psychiatrists in North America, and also elsewhere in the world, rely on the DSM to make their diagnoses and communicate them with others in the health-care profession.

But the manual’s immense influence is a problem says Edward Shorter, the Hannah Professor of the History of Medicine at U of T. He thinks that many of the disorders described in the DSM are not actual diseases discovered through the scientific method. Instead, they resulted from political deal-making among different factions in the professional community, each with conflicting ideas about causes and treatments of psychological problems. The result, he says, is a description of mental disorders with too little relation to real diseases.

In Shorter’s opinion, the manual sometimes pathologizes perfectly normal behaviour, while actual diseases get lost in a thicket of non-existent syndromes and disorders. And as the association works through a new revision of the DSM, it looks like things will only get worse, he says.

“The DSM continues to run off the rails in terms of its ability to come up with true disease entities that exist in nature,” Shorter says. “The problem is that the document itself is profoundly unscientific.”

Shorter is a social historian of medicine. He has written books on obstetrics and gynecology, the doctor-patient relationship, psychosomatic illness and psychiatry. His books include Written in the Flesh: A History of Desire, and Shock Therapy: A History of Electroconvulsive Treatment in Mental Illness (which he wrote with psychiatrist David Healy). One reviewer, Dr. Nassir Ghaemi of Tufts Medical Center in Boston, called his A History of Psychiatry from the Era of the Asylum to the Age of Prozac (John Wiley & Sons, 1997) “the best single volume to read on that topic.”

The American Psychiatric Association’s DSM guides treatment decisions in the U.S., Canada and other countries. Often a DSM diagnosis is required by an insurer before payments will be made for treatment. The manual’s categories are also frequently used by researchers studying mental disorders. And the categories influence the way we think about mental illness, and for that matter how we think about mental health.

The DSM has been in the news a lot lately as it goes through a fifth major revision, due to be published in 2013. Some critics have accused the task force that’s leading the process of excessive secrecy. Others have specific complaints about disorders they think should be included, or excluded or redefined.

But Shorter’s critique is more general. He thinks that the DSM is both an example and a cause of psychiatry’s wrong turn beginning sometime after the mid-20th century. He says the profession moved from a relatively small, relatively valid list of mental diseases – many of which could be treated effectively by tranquilizers, lithium and first-generation antidepressants – toward a vast list of disorders with no scientific validity. Some of the disorders overlap so much that they are almost impossible to distinguish from one another. Worse, he says, some of the disorders are really descriptions of normal, if difficult, human experience.

In the past there has been a consensus in psychiatry based on what is really wrong with patients. This sound body of wisdom of the ages has been ignored, Shorter says.

The DSM got its start in the early 1950s. The first version, published in 1952, reflected the then-prevailing psychodynamic viewpoint of psychology, with heavy emphasis on the complex interplay between personality and life history. The manual described 106 disorders, but with no strict criteria for determining if a patient had a disorder. A revision in 1968 didn’t change much.

But the 1980 revision took a radical turn. Dr. Robert Spitzer, a psychiatrist at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, was put in charge of the project. He wanted to move away from a psychoanalytic view of mental illness, and toward a more biomedical view. In the DSM III, disorders were supposed to be reliably diagnosed and categorized according to symptoms, in the same way that physical illnesses were. If you had enough of the symptoms on the checklist, you had the disorder.

The DSM III increased the number of disorders to 265. New disorders included major depression, attention deficit disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder and social phobia. Left out or downgraded were formerly important concepts such as neurosis. Although the DSM has gone through a significant revision since then, its underlying structure and philosophy have been left largely intact until now.

The current American Psychiatric Association task force, comprising 29 psychiatrists and other mental health specialists, wants to recognize that many conditions often overlap – for instance, anxiety and depression – so that a diagnosis of only one or the other doesn’t always make sense.

Perhaps most significantly, the new version of the DSM will also include a “dimensional” component – one that considers the severity of symptoms in making a diagnosis. This could lead to some symptoms being classified as below the threshold needed for diagnosis with an actual disorder, but still severe enough to be a problem. For instance, someone could be diagnosed with pre-psychotic syndrome or mild cognitive disorder. Shorter and other critics worry that this could further shift the line between what’s considered normal human experience and a pathology that requires medical treatment. For Shorter, the main problem with the new DSM is that it continues what he sees as the mistakes of the DSM III. Shorter plowed through the American Psychiatric Association’s records of the DSM III task force deliberations, and concluded that the process was largely a political rather than a scientific one.

At the time, Shorter says, there were two conflicting schools of thought within the association. Psychoanalysts, with their theory of mental illness as the result of unconscious conflict, were on one side. Supporters, such as Dr. Spitzer, of a biomedical model of mental illness were on the other side. Although the biomedical view largely won, the document the task force created showed signs of the political compromises, Shorter says.

For instance, our current ideas about depression – that it’s a single illness ranging from mild to severe – is a result of that compromise. Before DSM III, depression was generally considered to come in two distinct flavours. One was sometimes called neurasthenia, with relatively mild symptoms of general dysphoria and unhappiness. The other was full-blown melancholia, marked by mental and physical slowing, high levels of the stress hormone cortisol and feelings of personal worthlessness.

Over a number of years the task force considered many different terminologies for the various types of depression, including “major depressive disorder,” “chronic depression,” “neurotic depression,” “chronic minor depressive disorder,” “melancholia,” and “dysthymia.” Different interest groups favoured different terms, often based on whether they seemed to suggest a biological or psychological cause of depression.

Eventually, a compromise was struck. The biomedical side got “major depression,” which many of them considered to be “real” depression. The psychoanalysts got “dysthymia,” a concept that included “neurotic depression.” Since neurosis implied unconscious conflict, this was a diagnosis with which they could be satisfied.

Although on the surface this sounds like the old melancholia/ neurasthenia distinction, the diagnostic criteria that actually apply to them are different. Shorter says that the symptoms of major depression and dysthymia overlapped so much that they just about erased the distinction between a depression that was chronic and relatively minor, and fullblown melancholia.

“There isn’t any other discipline in medicine that depends on consensus for its scientific truths,” says Shorter. “Consensus really means horse-trading – I’ll give you this diagnosis if you’ll give me that diagnosis. That’s the way they do business in politics. That’s not the way you do business in science. The speed of light wasn’t determined by consensus.”

Even worse, according to Shorter, is the sheer number of disorders listed in the DSM. Although the listed disorders attempt to make fine distinctions, Shorter says they are largely distinctions without a significant difference. Distinctions between, say, social anxiety disorder and generalized anxiety disorder probably aren’t meaningful, he says. Both are probably going to be treated with the same drugs. Newly proposed disorders relate to hypersexuality, binge eating, hoarding and gambling. Also being proposed is “premenstrual dysphoric disorder.”

The multiplying disorders have also tended to pathologize our lives, so that feelings that fall within the range of normal human experience are sometimes interpreted as disorders. Dr. Paul Chodoff, a psychiatrist in Washington D.C., jokingly suggested in a letter to the journal Psychiatric News that there be a new diagnosis called “the human condition.” Diagnostic criteria would include “unhappiness,” “dissatisfaction with one’s looks,” and “getting upset when things go wrong.” In a more serious article called “The Medicalization of the Human Condition,” in the journal Psychiatric Services, Dr. Chodoff says that “… in their eagerness to include all varieties and vagaries of human feelings and behavior in their professional domain, [psychiatrists] are running the risk of trying to medicalize not only psychiatry but the human condition itself.”

According to a report from Health Canada released in 2002, 20 per cent of Canadians will experience mental illness sometime in their lives. Approximately eight per cent of adults will experience major depression, and one per cent will experience bipolar disorder. “There is such a thing as real psychiatric illnesses,” Shorter says. “But these diagnoses have simply gotten out of hand.”

“One of the disadvantages is instilling in people the idea that normal life includes chronic medication. This has been a terrible development in the last 30 years, the idea that you cannot have a normal life unless you’re on pills.”

Last year, Shorter published an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal laying out his criticism of various versions of the DSM, including the forthcoming edition. Among other things he complained about the proposed category of “psychosis risk syndrome,” for people who have either delusions, hallucinations or disorganized speech, but who are not fullblown psychotics.

“Let’s say you have ‘disorganized speech.’ This would apply to about half of my students. Pour on the Seroquel for ‘psychosis risk syndrome’!” Shorter wrote.

Not surprisingly, Shorter’s views have been criticized. His Wall Street Journal article drew a critical response from Dr. Alan F. Schatzberg, president of the American Psychiatric Association, who accused Shorter of falling victim to common misperceptions about psychiatry and diagnoses. It’s absurd, he wrote in a letter to the newspaper, to suggest that anyone would be diagnosed as having a specific disorder because of a single symptom.

Another letter came from Dr. Henry J. Friedman, a psychiatrist at Harvard Medical School, who described Shorter’s article as a “brutal attack on contemporary psychiatry.” In a phone interview, Dr. Friedman agreed that disorders listed in the DSM are proliferating, and may not describe actual organic diseases. But that doesn’t mean the diagnoses aren’t helpful, he said.

For instance, a person with social anxiety disorder has anxiety triggered by social situations. A therapist using cognitive behavioural therapy would help the patient focus on thoughts and feelings around social interactions. Treatment for a general sense of anxiety would be different. Dr. David S. Goldbloom, a University of Toronto professor of psychiatry, says that Shorter has identified a real issue in psychiatry − the underlying cause of a disorder is often not known. No blood test or X-ray can confirm a diagnosis. That means psychiatrists are left to make diagnoses strictly according to symptoms. But that doesn’t mean the diagnoses are without value.

“We, as clinicians, need a common language in order to communicate. That’s really what the DSM is and should be, rather than a statement of the ‘truth’ of psychiatric illness. That truth remains unknown.

“The DSM tries to incorporate the best available evidence of how symptoms cluster into recognizable disorders. Given the limits of the science there has to be some measure of expert consensus,” he says.

The problem of “diagnostic creep,” in which normal human emotions are classified as pathology is also a valid concern, he says. “Being sad, angry, afraid or joyous − that is part of the normal fabric of human experience. How do we draw a line when sadness becomes depression, when joy becomes mania, when fear becomes paranoia?” he asks.

Other branches of medicine face similar problems, he says. Blood pressure exists along a continuum. At some point, a doctor will diagnose a patient with hypertension based on a medical consensus of what a problem blood pressure reading is. The medical condition is real, but the criterion is necessarily arbitrary.

Dr. Goldbloom agrees that the DSM isn’t perfect, as you would expect from a consensus document. In the future, the committee may decide to eliminate some of the new diagnostic categories, or lump together conditions that are now split apart.

Nevertheless, Shorter thinks that we would all be better off if psychiatry would return to the days of trying to treat a few well-established diseases with clear organic underpinnings, such as melancholia. Most of the rest of what the DSM describes could be dealt with by trained psychotherapists, such as psychologists, social workers and nurse practitioners.

“There’s no doubt psychotherapy makes patients feel better. At the same time, I’m not in favour of training psychiatrists to be better psychotherapists. Their job is to make a diagnosis of biological origin and to treat them with effective agents.”

Kurt Kleiner writes about science and technology from Toronto. He blogs at http://organizedcommonsense.com

Edward Shorter and David S. Goldbloom and others discuss the upcoming fifth edition of the DSM on TVO’s The Agenda, with Steve Paikin

Recent Posts

U of T’s 197th Birthday Quiz

Test your knowledge of all things U of T in honour of the university’s 197th anniversary on March 15!

Are Cold Plunges Good for You?

Research suggests they are, in three ways

Work Has Changed. So Have the Qualities of Good Leadership

Rapid shifts in everything from technology to employee expectations are pressuring leaders to constantly adapt

3 Responses to “ Mind Games ”

Professor Shorter is spot on. When I was taking the Licentiate of the Medical Council of Canada (as a clinical fellow at the Banting and Best Institute in 1985) I learnt the DSM classifications like everyone else.

Now after many years practice I tend not to think in terms of the 265 psychiatric disorders, but more the four classics: the rest being poetry.

Sad: the heart sighs as the head has its way.

Mad: the head shakes as the heart holds sway.

Bad: the conscience crumbles as vice turns to folly.

Glad: the voice sings - but too loud and too jolly!

Graham J C Smelt,

Yorkshire, England

Prof. Edward Shorter’s views emphasize the medicalization of psychiatry, but fail to recognize how mental health professionals promote positive outcomes through listening to patients.

As a nurse practitioner on a psychiatry team in a busy urban hospital, I believe it is important for patient care to consider both the traditional biomedical model as well as a contemporary holistic framework.

Health is influenced by biological, psychological and social factors: a patient is a person, and not simply a product of a diagnostic label. Prof. Shorter’s stance mistakenly overlooks the contributions of psychotherapy. Research has demonstrated that major depression is more effectively treated with a combination of medication and psychotherapy than with either intervention alone. Psychiatrists, nurses, nurse practitioners and allied health professionals with specialized training in psychotherapy are well positioned to promote mental health patients’ outcomes.

Moving away from a cure-only paradigm will enhance the care of our patients, and more importantly, their ability to achieve more accessible and effective mental health treatment.

Brock Cooper

MN NP 2010

Toronto

The DSM is composed without concern for any causal explanations. In fact it's generally accepted in psychiatry that a cause does not need to be known before treatment is administered. What would the medical profession look like if medical doctors claimed that a cause does not need to be known before treatment is administered?

Peter Raabe

Abbotsford, B.C.