The view from the overnight police desk at the old Toronto Telegram was not pretty. It was 11:45 p.m. An irascible night editor was barking orders to a lonely copy boy stuck on the graveyard shift. How he had screwed up, no one seemed to know. But he was new, and the new guys were always screwing up.

I was one of three reporters assigned to arrive at 5 p.m. and work till 1 a.m., or later if the story merited it. Since overtime pay was mandatory, few tales ever found such merit. It was amazing to see how quickly even the most complicated accident/arrest/house fire/domestic act of violence could be summed up in five paragraphs as the shift approached its conclusion.

This was my first job. After I obtained a BA and an MA and painfully decided that I was not put on earth with the particular set of skills to pull off a PhD, the late-night police desk turned out to be the best job I could come up with. The Globe and Mail had turned me down. The Toronto Star had turned me down. Maclean’s had turned me down. The CBC had turned me down. Even today, 35 years later, I can remember how grateful I was when the offer came through from the Tely. It was the start of a career! An independent life! The start of paying off student loans! And all for the Southern Ontario Newspaper Guild’s starting rate of $139 a week.

The job, once obtained, was another matter. Waiting to hear from the worn-out, utterly defeated night editor about which accident or fire I would cover, I would muse at the contrasts in life. Just months earlier, for example, I had been enjoying dreamy days lost in 17th-century English literature, fussing over the links between George Herbert’s poem cycle The Temple and the pulpit oratory of Lancelot Andrewes. Or having lofty discussions with my earnest and exacting MA thesis supervisor on how to get going on my (actually, his) chosen topic: The Role of Art and Artifice in Seventeenth-Century Social Comedy (excluding Shakespeare). No torrid interviews with witnesses saying things like, “I was just driving along, you know, and then – God it’s just awful – this car swerved and, well, look at this mess…”

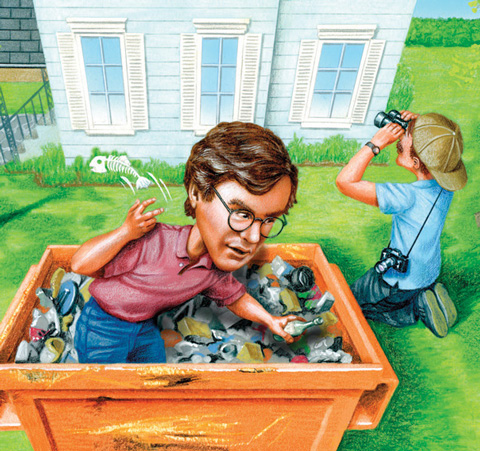

What I didn’t gain in intellectual stimulation from the Toronto Telegram, sire of the Toronto Sun, I more than made up for with police desk adventures. It was 1971, and at one point, in welcome relief from car crashes and fires, we thought we had tracked down Dr. Daniel Ellsberg – the U.S. academic who had given the Pentagon Papers to the New York Times – in the North York home of his brother-in-law. A tip had come in, and we staked out the house. Someone, I am sorry to report, even went through a pail of garbage, an act that really brings a thoughtful journalist to his senses about the cold reality of his profession. It turned out to be a neighbour’s practical joke – a joke we brought back to the newsroom by putting a green garbage bag over the head of a sodden sports writer named Paul Rimstead and telling the poor night editor we had Ellsberg “in the bag,” so to speak. Silly stuff, but we thought it riotous.

Then one day I heard that Kenneth Winters, the award-winning music and dance critic of the Tely, was quitting to become the executive director of the Ontario Federation of Symphony Orchestras. I had practical training in music, and I had academic credentials for theatre (well, theatre as literature rather than performance, but at the Tely such fine distinctions were mostly lost). So, with all the bravado of youth, I applied for Mr. Winters’ job, and a day later, to my amazement, I got it. In retrospect, I should have known then that the poor old Tely was about to fail, but that wasn’t at all what I thought. Five and a half months on the police desk had led me directly to the position of music and opera critic for a major metropolitan daily. My goodness, I was pleased with myself.

Imagine my chagrin, therefore, when I turned up for duty at my new post and was informed by the entertainment editor that I would be reviewing the Vienna State Opera Ballet’s performance at the O’Keefe Centre, starring Dame Margot Fonteyn de Arias, that very evening. Ballet? Me? This was an interesting juncture in my hardly begun professional career. Did I tell the editor I knew virtually nothing about ballet? No, I reasoned pretty quickly. That would not be astute on the first assignment. So I simply asked what time the show started.

“Figuring that out is part of your swell new job,” he growled.

I guessed from the sarcasm that I wasn’t the editor’s favourite choice to succeed Mr. Winters. Perhaps he hadn’t even been consulted. It was a cautionary moment. I proceeded to find out what time the show started and quickly researched how to fake my way through a ballet review. This was before Google, so I actually had to sift through old clippings and dusty books. Imagine! In those days, also, reviewers had to write on daily deadline, so I was required to rush back to the Tely right after the performance and write the piece in an hour and a half.

Luck favours everyone sometimes. Poor old Dame Margot was past it, but she had a grand presence. Some innate sense of the appropriate told me to celebrate her career without stint and forget the current specifics. At the same time, without really understanding why, the Vienna State Opera Ballet was clearly a bit of a joke. There was a short offering by George Balanchine, for example, which required the men to wear very simple outfits: white T-shirt and black tights. Very cool, very clean-lined, except that the men of the Vienna State Opera Ballet were the artistic equivalent of civil servants with secure jobs paid for by the state. Their emerging waistlines showed how content they were. I’m afraid at some point in the review I wrote that if wiener schnitzel and schnapps could dance they would look like the Vienna State Opera Ballet, which was cruel. But the line secured me sufficient notice to keep the job, keep the editor off my back and – nine months later, after the Tely had folded – get the position of dance writer and backup music critic for the Globe and Mail, which was where I’d really wanted to be right from the beginning.

I never regretted abandoning doctoral studies for journalism. As George Herbert coolly observed in his 1640 collection, Outlandish Proverbs: “I had rather ride an asse that carries me, than a horse that throwes me.” Ultimately, that good “asse” brought me back to the academy where I am happily able to ride.

John Fraser stayed at the Globe and Mail for 17 years. An award-winning journalist and author of eight books, he has been Master of Massey College in the University of Toronto since 1995. In September, he will begin teaching a newly offered course in Canadian newspaper history at St. Michael’s College.

Recent Posts

U of T’s 197th Birthday Quiz

Test your knowledge of all things U of T in honour of the university’s 197th anniversary on March 15!

Are Cold Plunges Good for You?

Research suggests they are, in three ways

Work Has Changed. So Have the Qualities of Good Leadership

Rapid shifts in everything from technology to employee expectations are pressuring leaders to constantly adapt