Public outrage over sky-high executive pay isn’t new, but it has taken on a particularly virulent tone in the unfolding financial crisis. “Resign or go commit suicide,” Charles Grassley, a Republican senator, advised the executives of American International Group in March. The execs had rewarded themselves with $220 million in bonuses after the insurance giant accepted $180 billion in taxpayer money. Similar stories – Merrill Lynch employees claiming billions in bonuses despite driving the near-century-old investment bank to the brink of insolvency – are fuelling calls for the regulation of executive pay, and possibly capping outsized compensation packages.

However, Roger Martin, dean of the Rotman School of Management at U of T, says the real problem is not how much executives get paid, but how. A widely accepted 33-year-old management theory advocates paying CEOs with stock options to align their interests with those of shareholders. This practice should be scrapped, says Martin.

He argues that a CEO’s compensation should relate to how well a company performs in the real-world market, not on the stock market. It should be based on “real-market measures” such as return on equity, return on investment, and increases in sales or market share. “Executive pay should have no component of stock-based compensation at all,” Martin writes in the spring issue of Rotman Magazine. “Incentives should also be aligned to real-market performance.”

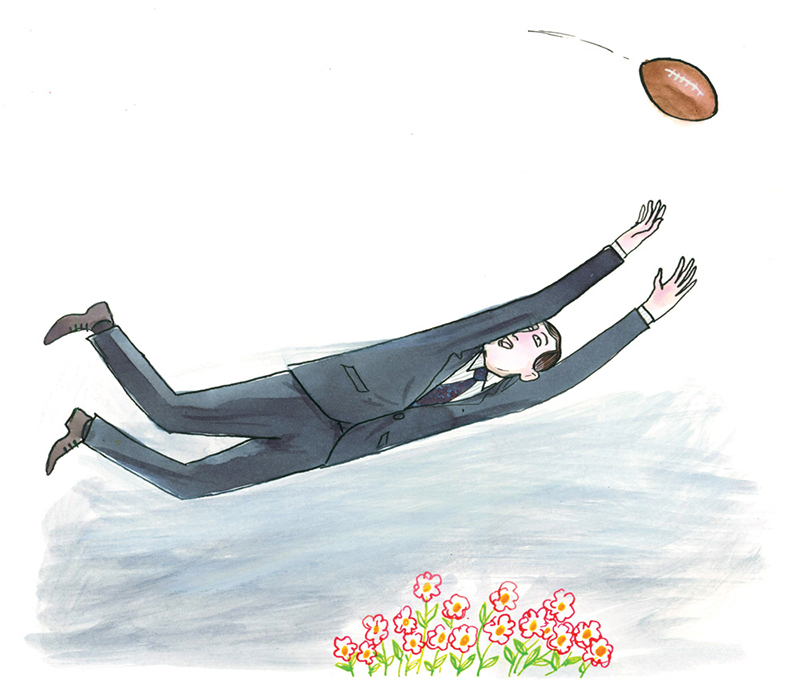

Martin illustrates his point by drawing an analogy between the corporate realm and the National Football League. Both operate in a “real market” and an “expectations market,” he writes. In football, the real market operates when the teams go head-to-head on the field, score touchdowns, and win or lose the game. In business, the real market is the world of factories, production, sales, profits and losses.

However, in both football and business, expectations drive a separate market. In football, it’s sports betting (in which people place money on the team they expect to win the next game, and by how much). In business, expectations drive the stock market. And this is where the two worlds differ: “In football, the goal is to win the game in the real market,” writes Martin. Players and coaches receive pay incentives based on the team’s performance on the field – not based on whether they beat the Las Vegas point spread. “In business, however, the focus of real-market participants – executives and workers – has increasingly shifted to the expectations market,” he writes. Winning is no longer about steadily increasing sales or profits over the long term. “Winning means increasing your stock price.”

Martin argues that stock-based compensation models encourage CEOs to focus on raising their company’s stock price in brief spurts rather than working to improve the company’s long-term health in the real market. The results can be disastrous, he says, citing former Qwest CEO Joe Nacchio as an example of a manager who followed the wrong approach. “If we are to emerge from the current mess, executives must switch their focus entirely to the real market and completely ignore the expectations market,” he writes.

Recent Posts

For Greener Buildings, We Need to Rethink How We Construct Them

To meet its pledge to be carbon neutral by 2050, Canada needs to cut emissions from the construction industry. Architecture prof Kelly Doran has ideas

U of T’s 197th Birthday Quiz

Test your knowledge of all things U of T in honour of the university’s 197th anniversary on March 15!

Are Cold Plunges Good for You?

Research suggests they are, in three ways