Today we think of a holy book as complete and inviolable. But the ancient people who wrote and preserved the Dead Sea scrolls probably saw them the way we see Wikipedia – authoritative, but also fluid and constantly open to expansion and revision.

This is the argument of Eva Mroczek, a doctoral student at the Department and Centre for the Study of Religion and the Centre for Jewish Studies.

Our contemporary culture tends to think of a published work as the finished product of a single author. But the Internet is starting to change how we regard writing, making it a more social, co-operative act – one that is always open to expansion and revision. Mroczek’s research suggests that this attitude toward text is similar to how ancient communities regarded the Dead Sea scrolls. “What I’m interested in is the way that the culture that is represented in the scrolls imagined text,” she says.

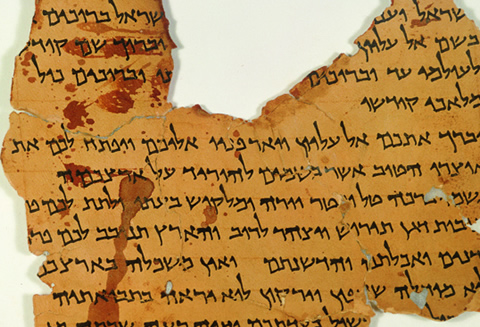

The Dead Sea scrolls consist of about 900 separate documents, including the earliest copies of some of the books of the Hebrew Bible. The scrolls date from about 250 BCE (before the Common Era) to 68 CE, and may have been kept by a Jewish sect that lived in the nearby settlement of Qumran.

Mroczek says the scrolls were held in high regard as physical objects. Their keepers wrapped them in linen and painstakingly repaired and carefully stored them. But at the same time, the content of the scrolls was not rigidly protected. The scribes who recopied the scrolls updated, revised and even added to the collection.

This attitude was probably partly due to the physical nature of the scrolls. While a book’s two covers suggest that the work is finite and complete, a collection of scrolls set in no particular order suggests a work you can rearrange, expand and revise. “One way of thinking about it is that less is not more,” says Mroczek. “As a scribe, the more you could write, the more you could transmit, the closer you could get to some vast divine system.”

The Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) is running an exhibit on the Dead Sea scrolls until January 3, displaying 17 of the ancient documents. In conjunction with the exhibit, Mroczek and fellow grad student Chad Stauber are assisting with preparations for The Dead Sea Scrolls: Transmission of Traditions and Production of Texts, an international conference of scholars to be held from November 15 to 18.

The event is the brainchild of Hindy Najman, the director of the Centre for Jewish Studies and a professor of ancient Judaism at U of T, and Sarianna Metso, a professor at U of T Mississauga who specializes in the Hebrew Bible and Dead Sea scrolls. They enlisted the help of Judith Newman, a professor of ancient Judaism at U of T, Eileen Schuller, a professor at McMaster University, and Alex Gropper, a teacher at the Tanenbaum Community Hebrew Academy of Toronto.

Najman, who is also a professor in the Department and Centre for the Study of Religion, invited top scholars from Israel, Canada and the United States, to attend. She will deliver a ROM lecture on the scrolls in early December.

On the conference’s last day, eight graduate students from U of T and McMaster – including Mroczek and Stauber – will present papers. Mroczek says she’s happy the show has ignited the interest of the public, including friends and acquaintances. “Everybody wants to know what I’m doing, which is very, very unusual for me,” she says.

Recent Posts

For Greener Buildings, We Need to Rethink How We Construct Them

To meet its pledge to be carbon neutral by 2050, Canada needs to cut emissions from the construction industry. Architecture prof Kelly Doran has ideas

U of T’s 197th Birthday Quiz

Test your knowledge of all things U of T in honour of the university’s 197th anniversary on March 15!

Are Cold Plunges Good for You?

Research suggests they are, in three ways

One Response to “ Revelations from Qumran ”

This is the best article I've read so far this year. I think Muslims, Jews and Christians should all read and understand it so we can avoid these waves of fanaticism. Thank you Eva!