The University of Toronto’s midtown campus is solidly 19th and 20th century, yet its neo-Gothic and red-brick structures have somehow provided the impetus for amazing flights of fancy about medieval fictional worlds. The university’s community of medievalists gave Caroline Roe the idea for her Isaac of Girona crime series, and it’s not a great leap from Girona in 14th-century Spain to the fictionalized medieval Spain of Guy Gavriel Kay’s The Lions of Al-Rassan. Like Roe, Kay has retained his connections with U of T. He gives readings in the Hart House library, which he says is one of his favourite places on the planet.

Like his father, a Winnipeg surgeon, Guy Gavriel Kay always had a passion for writing. After graduating in philosophy from the University of Manitoba, he went to Oxford to work with Christopher Tolkien, son of the Anglo-Saxon scholar and celebrated fantasy writer, J.R.R. Tolkien, on the senior Tolkien’s last major manuscript.

But, again like his father, Kay was a pragmatist, so he returned to Canada to find a profession – knowing that making a living as a novelist would be a long shot. Kay entered the Faculty of Law at U of T in 1975 and graduated in 1978. At first he found the place decidedly uninspiring. “I arrived from rural England, and there I was at school in downtown Toronto, and I just hated it,” says Kay. “I hung around the Hart House library and read The New Yorker to remind myself that I really was a writer.”

He did well (in fact he came second in his first-year law class), even though he could often be found at the pinball machine in the law-school basement. Looking for more intellectual diversion, he cut a week of school to attend a major conference on Celtic studies at U of T. Here, he encountered the scholar/guru who had awakened a generation of North Americans to the power of myth, Joseph Campbell, author of The Hero with a Thousand Faces.

That conference inspired the opening chapter of Kay’s first book, The Summer Tree. It opens in Convocation Hall on U of T’s campus and introduces a Joseph Campbellish figure who turns out to be a mage (or benign sorcerer). The book was the first volume of Kay’s Fionavar Tapestry series and won an international cult following. A few years ago his agent joked that the continuing sales of the Fionavar books would help Kay and his wife, Laura, put their sons, Sam and Matthew, through college.

An ambitious man, he eventually pushed past the frontiers of fantasy into a new sub-genre, speculative historical fiction. In 1990 he brought out Tigana, which takes place in an imagined world much like Renaissance Italy, and, in 1992, A Song for Arbonne, set in a fictional medieval Provence. In 1995, he released The Lions of Al-Rassan, which describes a multiracial society akin to Moorish Spain.

These historical fantasies grow out of intense research (“I get grad-student syndrome,” Kay admits. “I don’t want to write until I’ve checked one last detail”). Remarkably, the author has retained the loyalty of the fantasy market – this spring he was guest of honour at the British National Science Fiction Convention in Glasgow – while also winning respect from that toughest of audiences, academics.

This spring the head of the classics department at the University of Vermont asked Kay to speak there. She had just read Sailing to Sarantium (like his latest novel, Lord of Emperors, it is set in a place much like sixth-century Byzantium, rife with charioteering factions, religious rivalries and Byzantine intrigue). Come autumn, Kay will speak at U of T’s Convocation Hall about ethics, society and the role of narrative – “something about how we all, professional historians included, construct the narratives we need out of a set of events,” says Kay.

As one who has worked hard to transform raw material from the imperial reign of Justinian and Theodora into an imaginary realm, he is disturbed by the co-option of real characters into fiction by contemporary authors; he sees this as a symptom of the way we undervalue works of pure imagination. “Don’t get me onto my soapbox!” he warns.

With eight books translated into 16 languages, Kay is one of Canada’s most successful writers, and he is not shy about extolling the power of the storyteller. “That’s who the Lord of Emperors is: the writer, the artist,” he says, “the person who leaves the record of what the kings have done.” Which is why libraries like the one at Hart House still cast a spell over him. “There’s a ghost there, my younger self, reading The New Yorker, and asserting my identity as a writer.”

Caroline Roe

Caroline Roe

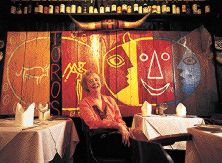

When she writes the name of the town “Girona,” Caroline Roe uses the Catalan spelling, as opposed to the standard Castilian Spanish “Gerona” you’ll find on most maps of northern Spain. “It’s political,” says Roe, the creator of the successful new Isaac of Girona paperback mysteries, starring a 14th-century Jewish doctor.

There are three Isaac mysteries out already, published by Berkley Prime Crime, and two more are in the works. Already published in Spanish, Isaac’s first adventure, Remedy for Treason, was launched last year in a Catalan translation in Girona. Roe (BA 1962 UC, MA 1968, PhD 1974) flew from her home in Toronto to the city of 72,000, which, she says, has probably the best-preserved walled Jewish quarter left in Europe. Girona’s mayor uncorked champagne and Roe thanked him in Castilian, all the while wishing she knew more Catalan. She has spent this past winter learning the language at U of T.

Languages come easily to her. Her mother was a professional opera singer, so perhaps it’s in the ear. In any case, after high school in Windsor, Ont., she studied modern languages at University College, with a bent toward Old French, Spanish and English. It was the early 1960s, and even though women couldn’t be members, she hung out with the music crowd at Hart House and played with the Paul Robinson classical string orchestra, which performed some concerts there.

Something else seems to come easily to Roe: her ability to vividly recreate the smells, tastes and mores of Isaac’s times. This gift is rooted in scholarship: she did her PhD in 1974 in “vernacular didactic literature in England in the 12th and 13th centuries.” A former chair of the medieval studies student committee, she met her husband Harry Roe (author of the newly published translation Tales of the Elders of Ireland) in the rambling, old Centre for Medieval Studies on Queen’s Park Crescent and still counts medievalists among her closest friends.

The medievalists also gave her her new fictional sleuth. For 17 years, after completing her doctorate, Roe taught English at Branksome Hall, the private girls’ school in Toronto, and in 1979 began writing mysteries in the summers under the name Medora Sale. She won the Arthur Ellis Award for best first crime novel in 1986, but in the early 1990s the market for a feminist detective in contemporary Toronto dried up and Sale/Roe’s Harriet Jeffries series ended with the sixth book – leaving Roe to wonder what she would write next.

The answer came as she was chopping vegetables for a medievalists’ party. A friend told her about Bishop Berenguer of Girona, who was known to have had a Jewish physician. This doctor was not Isaac of Girona (he was a philosopher and kabbalist who lived in Narbonne, France a century earlier). “But his students are known to have gone to Girona,” says Roe, “so I’ve imagined my Isaac as a student of his students.”

Remedy for Treason was shortlisted in 1999 for both an Anthony Award (in the United States) and an Arthur Ellis Award, and the Isaac novels have been well-received: “Finely written, well-plotted” said The Washington Times. “Should go instantly to the top of any Cadfael-lover’s list,” said The Globe and Mail, citing the best of the historical mystery sub-genre, Ellis Peters’ Brother Cadfael series. In fact, there’s a boom now in historical crime – “you need to line up in England to book a year and a plot of ground,” Roe jokes.

She doesn’t give all her fellow writers full marks. An active member of Crime Writers of Canada and former head of Sisters in Crime (the international coven of women mystery writers), Roe says with a sunny smile, “I’ll tone down my natural bitchiness, but I will say there’s a split between those people from the research side and some from the commercial-fiction side.” Anachronisms strike her like an off-note in music.

Deep into research for the gentle, blind, shrewd Isaac of Girona’s next adventure, Roe slaves to get her history right. “You have no idea how hard it is to find out how long it took a 14th-century galley to sail from Barcelona to Sardinia,” she sighs. But find out she will.

Val Ross (BA 1972 UC) is a Toronto writer and editor.

Recent Posts

A Sentinel for Global Health

AI is promising a better – and faster – way to monitor the world for emerging medical threats

The Age of Deception

AI is generating a disinformation arms race. The window to stop it may be closing

Safety First

AI has developed faster than anyone thought. Will it serve humanity’s best interests?