One evening last spring, the Toronto International Film Festival’s Bell Lightbox played host to the homecoming of a Canadian born filmmaker. After six decades in show business, working mainly abroad, Ted Kotcheff (BA 1952 UC) was screening a beautifully restored and digitized version of his main Canadian-made success, The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz – based on the book by his great friend Mordecai Richler. Kotcheff shot and produced the film in 1973 during an interlude in Canada after more than a decade working in London and before moving to Los Angeles, where he lives now. He told the crowd how hard it was to raise enough money to make the movie.

I wasn’t there but Kotcheff recounted a version of the story to me when I visited him for an interview at his retreat in Mexico, north of Puerto Vallarta. “I found a Hollywood producer who was interested in making the movie. He thought the book was great. But he said Montreal was too parochial. Why not move it to Pittsburgh? And maybe we could make Duddy a Greek boy. It was my friend’s book, I couldn’t do that to him. Duddy – a Greek boy? In Pittsburgh?”

As it turned out, funds were found in Canada, and Kotcheff’s movie was set in and around Montreal – on a gritty St. Urbain Street, in the mansions of Westmount, on McGill University’s idyllic campus and in the nearby Laurentians. It starred a young, twitchy Richard Dreyfuss, then relatively unknown, as a decidedly un-Greek Duddy.

The movie did well at the box office: it earned back its small budget and then some. It also won critical plaudits. All in all, Duddy’s fictional coming-of-age story provided an actual coming-of-age moment for Canada’s nascent cultural scene. Both book and movie grab you by the lapels. In both versions, Duddy is brash, lovable, treacherous, part mensch, part schemer – and impossible to ignore.

This past spring, the Cannes Film Festival named Duddy Kravitz a “classic” and invited Kotcheff to a screening of it. The designation is an honour best measured by the quality of the other films included among this year’s classics: Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo, Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Last Emperor and Jacques Demy’s The Umbrellas of Cherbourg. In 2009, another film Kotcheff directed in the 1970s – the harrowing Wake in Fright, set in the Australian outback – was also screened at Cannes. Although directed by a Canadian, it’s considered one of the best Australian films of all time.

These two early films, both hits on the festival circuit, put Kotcheff on the international radar. In addition to significant theatre and television work, he has shot 19 feature films. He’s directed such A-list actors as Gregory Peck, Ingrid Bergman, Jane Fonda, Nick Nolte and Gene Hackman. His most well-known movies are a pair he did for big Hollywood studios in the 1980s: the Sylvester Stallone vehicle First Blood (the original Rambo movie), and the comedy Weekend at Bernie’s – both major commercial successes that spawned franchises. Kotcheff spent the 10 years before retiring – roughly the first of the new millennium – running the popular TV series Law & Order: Special Victims Unit. (To find good actors for the show, he estimates he watched more than 23,000 auditions.)

And now, with an old University of Toronto chum’s help, the former literature student has finally had time to realize a dream of his youth: to produce a collection of poems, revisiting key scenes and relationships from his past. Getting the chance to engage in some sustained contemplation after a life of lights, camera, action has been sweet enough in its way. But sweeter still: in the years after he took himself off the active for-hire list, his standing as a filmmaker hasn’t declined, but risen, and risen dramatically – in large measure because of Duddy Kravitz and Wake in Fright.

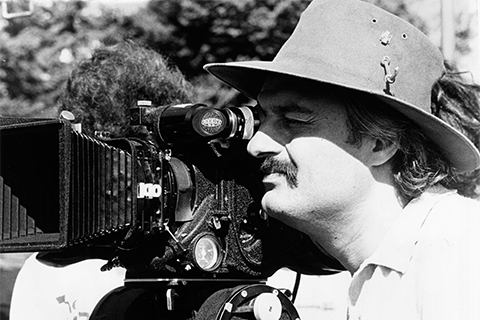

The photos of a young Kotcheff on set generally show him in a battered hat, gesticulating – sometimes angrily – at some well-known actor or his crew. His unruly, then-brown hair, sometimes hippie length, pokes out in all directions. Now in his early 80s, he’s changed some, but there’s still a fair bit of thatch up top even if it’s no longer brown and down to there. Under a strong brow are eyes that are friendly, but that pay close attention. He moves gingerly these days, sometimes stifling a wince: his back is playing up – and surgery is only a few days away, something he doesn’t once mention.

Kotcheff’s second wife Laifun Chung is an award-winning landscape designer, also a Canadian and the mother of two of his five adult children. She’s the more practical one of the pair, the driver, and the one who chose their apartment’s lush Frida Kahlo colours. She and Kotcheff also share a house in Beverly Hills that friends describe as a light-filled minicastle with a panoramic view of the city.

All of this is a far cry from what Kotcheff calls the slum house in Cabbagetown where he started his life. But his family’s relatively financially straitened existence had its compensations. In the pre-television era, Kotcheff and his father went to lots of movies – “sometimes four or five in a single week” – and both he and his younger brother Tim, later a Canadian television producer, caught the moving picture bug. But he wasn’t particularly close to either parent. “They worked hard. They were both immigrants from Bulgaria, she was of Macedonian descent, and they met over here around the time of the stock market crash. When I was born, they were just trying to make ends meet.”

Kotcheff remembers them distilling moonshine in the house – hooch they sold for extra income during the lean years of the ’30s. “It was a different Toronto. When my parents got married they had to do it on a Sunday, every other day they were working. And their good Protestant neighbours called the police to shut the music-filled party down.”

In a moment right out of Cinema Paradiso, Kotcheff used to sit backstage at a community hall while his parents and their emigrant friends put on a weekly theatrical in Bulgarian. “They’d write their own scripts. Often the actors, working other jobs, didn’t have time to learn the lines. So there’d be a huge amount of prompting, but still with all the pauses, the overacting, the underacting, you’d see the rapt faces in the audience, the crying, the happiness. They couldn’t get enough.”

Although money was tight, his parents found enough for violin lessons for Kotcheff, and under the tutelage of a young Slavic immigrant, he became one of the best young violinists in the country, winning a gold medal at age eight for his playing at the Canadian National Exhibition. But the tutor came back from fighting for Canada in the Second World War with a crushed hand, and Kotcheff, under a less inspiring teacher, dropped his aspirations to become a professional musician. But all the music-making had an impact: he still marks film scripts with musical pacing and mood notes. “This scene is andante, this one allegro, that one is largo.”

In the course of his arts degree at U of T – he had previously dropped out of a science degree – he took classes with two of the biggest intellectual lions at the school then, Marshall McLuhan and Northrop Frye. It was in Frye’s graduate seminar, a class Kotcheff snuck into, that he met Francis Chapman, a fellow student who would become a lifelong friend. Chapman, who became a TV and film director, producer and writer, recently helped Kotcheff get his poems into shape, and Kotcheff has given minor characters in his early films variations on his friend’s name.

Chapman’s family house in Rosedale became the young Bulgarian’s second Toronto home. “When you don’t find what you’re looking for in your home, you go for it elsewhere,” Kotcheff observes. The Chapman matriarch was a concert pianist who enjoyed playing chamber music with the talented Kotcheff. He used to flirt with her outrageously, notes Chapman, “saying if she’d only been a bit younger…”

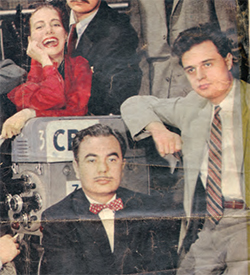

Kotcheff took the directing job, and remembers the period fondly: “We did everything – comedies, dramas, documentaries. It was live television, a new medium.” He became a versatile filmmaker, and attributes his desire to work in different genres to his beginnings at the CBC. He also started to entertain the idea of leaving Canada. “After a while, I wanted to try my hand at film – and theatre. There was no film industry in Canada and not that much theatre. In London, I could do all three.” Politics also played a part. Kotcheff’s participation in a left-leaning book club had gotten him barred from an America then seeing reds under every bed – and on every incoming train and boat. “They stopped me in St. Alban’s, Vermont, and held me there, for this book club I’d belonged to for six months a long time before.”

And so Britain looked doubly desirable, and, in the 1950s, Kotcheff went there, soon landing some solid TV work. Before the decade was out, he won the British equivalent of an Emmy. He also started to direct theatre. These were his glory days. One night, he took in an early Rolling Stones show at a small club, with novelist friends Penny and John Mortimer, the latter the author of the Rumpole of the Bailey series. “Penny said I had the sexiest lower lip in all of London – a compliment you don’t forget.” His first film gig came his way in 1962: Tiara Tahiti starring James Mason. It’s a meditation on class, with Mason playing a swell who falls on hard times; its credits indicate that a certain Mordecai Richler worked on the script.

The partnership that produced one of Canada’s best movies was not merely a professional one. But their first encounter seemed unpromising. Introduced by a mutual friend, they met for a meal in the south of France. Kotcheff chatted away, and a suspicious or moody – or something – Richler said next to nothing. “But then he apologized later for that, and anyway, something about it worked.”

The two would live together for nearly five years in a seldom locked run-down flat in Swiss Cottage, London, with the Canadian expat community wandering in and out. Kotcheff was there when Richler completed Duddy in the late ’50s, read it, and knew at once it was something special. “I said someday I’d fi lm it, and we both laughed at how unlikely it sounded.” An outsider in WASPy Toronto, Kotcheff felt for Duddy, a Jew who didn’t fi t into a Quebec divided between Catholic francophones and Protestant anglos.

Kotcheff was in the apartment when the advance copies of Duddy arrived. An unexpectedly dramatic scene ensued. “Richler’s first wife, Catherine, came in, opened a copy and saw the dedication – to another woman,” he recalls. “She went hysterical.” The woman the book is dedicated to, Florence, became Richler’s second wife, and they remained married for the duration of his life.

Both Kotcheff and Richler had big, often operatic relationships with women, but in a curious way, their relationship with each other often took precedence. They were so inseparable in London that sometimes they’d be suspected of being a couple. “Mordecai would play it up,” Kotcheff says. “He’d say, ‘In the early days with Ted, it was all cognac and cigars, but now what does he bring me? Nothing!’ and I’d play along saying, ‘Oh, shut up darling.’”

Richler’s eldest son Daniel remembers the drinking buddies’ Yuletide ritual: “The Richlers and Kotcheff s used to alternate Christmases at one another’s London homes. I’m not sure how much fun the wives had – our mom did all the cooking and Ted’s first wife, English actress Sylvia Kay, did most of the smoking at the window – but the men partied hearty. One especially boisterous year . . . I watched with nervous interest as Dad poured a slug of Scotch into his champagne. Ted called out, ‘My God, Mordecai, that’s a potent drink!’ and Mordecai said in the mock-boastful voice he liked to use, ‘A potent drink for a potent man.’” (Kotcheff ’s best movies focus mainly on men, on the moments, like this one, when they feel powerful, and those when they feel anything but.)

As Kotcheff ’s list of stage, film and TV credits grew, he began to think more seriously about filming Duddy. After the Hollywood producer’s ill-conceived proposal to transform the story out of recognition, Kotcheff approached the newly established Canadian Film Development Corporation. It decided to make Duddy one of its first big investments – providing $300,000 toward a $750,000 budget (the film went over budget to a total of $900,000). A Montreal property developer funded and arranged the rest, notwithstanding that Duddy himself makes a shady property development deal. At first, Kotcheff retained a lawyer-turned-writer named Lionel Chetwynd to draft the script. But it needed additional work, so Kotcheff brought in Richler, a novelist with a great ear for dialogue.

The film was a big critical success and a moderate one at the box office – it earned back its production budget in its first two weeks, and another $1.1 million to boot. Kotcheff , then permanently back from Britain, in Canada, hoped to build a film career here, on the strength of Duddy. “But nothing happened. I worked for a year on what I thought was another viable project. Nothing. So when they called from Hollywood, I went.”

***

In his poems, Kotcheff has revisited key moments in his past – an English teacher at Runnymede Collegiate who turned him on to Shakespeare, his violin teacher’s war injury – and a few are dedicated to deceased friends. Only Richler merits two poems – and both are moving. In one, he’s written: “You knew the curse of my life/That haunted me from childhood… Your look dispelled it forever.”

I don’t expect Kotcheff to answer when I ask him what that curse was. But he does: “There was lots of good in our household growing up, music, fun; they were fine people. But there was,” a long, long pause. “There was . . . When my father came home, my mother would tell him what I’d supposedly done that day, and I’d get it. He’d . . . I was convinced there was something in me that wasn’t lovable, that couldn’t possibly be loved. And Mordecai changed that for me.”

There’s not the slightest bit of self-pity in his voice. His youth was, it happened. He made friends and found mentors and other families to get what he needed. By today’s standards, Kotcheff’s films are not particularly violent. But the beatings he took growing up explain something about his art: the violent bits don’t have much musical highlighting or extreme lighting. Violence is a part of life, not anything particularly out of the ordinary.

As he surveys the Mexican coast, Kotcheff points out the birds flying along it, the pods of pelicans skimming the waves. After a long interview, he says, by way of summary: “I was happy those films came back [to Cannes]. It helped make me feel . . . like I’ve done something solid.”

He’s promised his papers, in due course, to U of T, and some of the biographers of the stars he’s worked with will no doubt pore over them. Perhaps his own biographer will, too. In the meantime, he’s not quite done, he has two unrealized ambitions: to direct an opera, and to find funding for a film about Bulgaria’s King Boris III, and how he worked to stop the Nazis from killing many of his country’s Jews.

“I may not get there, but so many of the things I wanted to do,” he says, “somehow I’ve done them.”

Alec Scott (LLB 1994) splits his time between Toronto and San Francisco. He writes frequently about the arts and travel.