The hallway of U of T’s department of Italian studies, like most academic corridors, contains an oppressive stillness. Behind closed office doors, professors may be deciphering the allegories of Dante’s heaven and hell or ruminating on the writings of Boccaccio, but the main hallway is damp with silence.

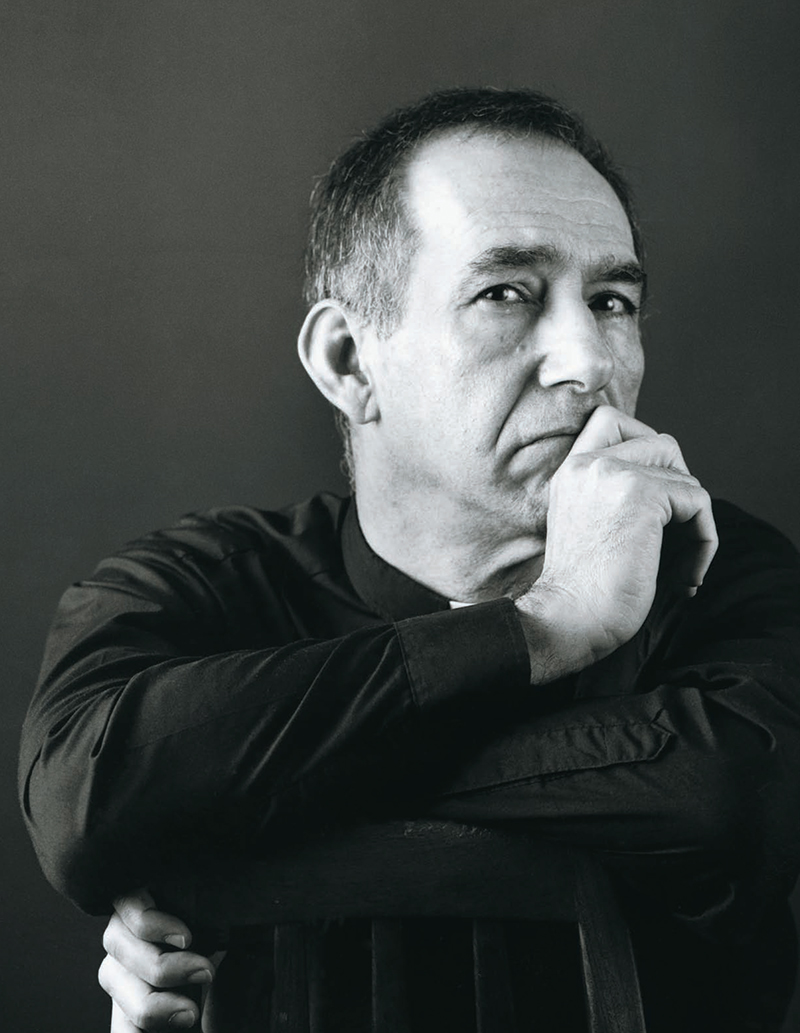

That quietude is dissolved – if only for a moment – by Pier Giorgio Di Cicco, Toronto’s newest poet laureate and a visiting professor of Italian-Canadian studies at U of T. He is slipping away from his office for a break, and has brought his digital recorder for his walk. He hits play, and a recording of 1950s crooner Jerry Vale’s “This is the Night” strains through the miniature speaker. “This is the night, it’s a beautiful night and we call it bella notte…” He hums happily. An assistant peers guardedly out of her office. “This song reminds me of an Italian restaurant on Mulberry Street in New York that I’ve never been to,” he says. “An Italian restaurant with heaping plates of spaghetti, and a pergola overhead with plastic grapes attached to it.”

Outside the building, Di Cicco lights a Matinée king size. He is down from the two-pack-a-day habit of his youth to one pack. (“You can quote me,” says his friend Rector Robert Nusca. “Tell him he’s got to stop having five cigarettes for every espresso.”) Students scurry past, heads down, intent on getting to class. From beneath his moss-green, brimmed hat, Di Cicco watches them curiously. He notes – in an almost injured tone – “Everybody is always hurrying. Always going somewhere.”

It doesn’t take much time with Di Cicco (BA 1973 University College, BEd 1976 OISE, MDiv 1990) to realize it’s not the “going somewhere” he objects to, but the manner of the journey. He believes people need to “see their daily lives as a poem” – and this requires incorporating art and poetry into the business of living. Back in his office, he speaks in the same slightly wounded tone as when looking at the students walking by. “Art is not out there. People think it’s out there. The creative product is not outside of them. How can they see it, if they don’t know it is in here?” he asks, pointing to his heart. “If they don’t see themselves as writing the poem of their life, their daily life, why should they read a poem?”

It’s a mindset he brings to the role of poet laureate of Toronto. In December, during his inaugural speech at Toronto City Hall, he urged a change of attitude – a new way of seeing ourselves and the city – that incorporates the notion of artistry and citizenry into one ethos. “A vibrant urban art teaches the art of life; but if the daily life is not artistic, inspired by intimacy, zest and sociality, the passion is missing, and a city without passion is just a series of artistic events,” he said. “Toronto has succeeded at just about everything, except looking glamorous to itself; and by glamour I mean a city’s attraction to its own uniqueness, moved by the conviction that there is a style of creativity that can only be done here.”

Di Cicco was appointed poet laureate of Toronto – a position of cultural ambassadorship – in September and will hold the post until 2007. He takes over from Dennis Lee (BA 1962 Victoria, MA 1965), Toronto’s first poet laureate and the author of such poetry collections as Un and Nightwatch and the children’s classic Alligator Pie. At the age of 56, Di Cicco has produced 17 books of poetry, each one radically divergent in scope and voice. From the powerful neo-surrealist images that first emerge in A Burning Patience (1978) to philosophic meditations incorporating science and art in Virgin Science: Hunting Holistic Paradigms (1986) to the exploration of spirituality and faith in The Honeymoon Wilderness (2002), his work constantly shifts its shape. His latest collection, Dead Men of the Fifties, reveals another departure in voice. With the mirthful energy of a swing dancer and the comic timing of Jack Parr, Di Cicco jitterbugs his way through the landscape of the ’50s, casting an eye on Hollywood stars, musicians and the everyday people of the post-war decade.

Like his poetry, Di Cicco’s journey is filled with a series of radical turns. He was born in 1949 in Arezzo, Italy, south of Florence, where he lived until the age of three. He has three memories of that time: A palm tree outside the room in which he was born. The billowing waves of the Mediterranean. His grandmother’s bouffant hairdo. “All the others are textured memories of the synesthetic kind,” he says. “Because when I was a kid, before they taught me Aristotelian senses, I could smell colour, feel music.” His father was a barber who played the accordion in dance bands. His mother, a homemaker, sang him arias and love songs.

Before his birth, during the Second World War, his brother was killed during an Allied bombardment in the area between Naples and Cassino. His mellifluous voice turns low and staccato when he speaks of it. “My brother – died – from a shell –. I had a brother who –. I had a brother who I never saw. I think he was 13, maybe 12, when he was caught in the bombing.” He takes a deep, cavernous breath and shifts to another subject. His father’s barbershop was also levelled during the bombings.

The family, which includes an older sister, moved to Canada to rebuild. They lived in Italian communities in Montreal, then Toronto, where, Di Cicco says “the culture remained encased in amber.” But that refined Italian ambience was swapped for a steel-town existence when the family moved to Baltimore when he was eight. The city certainly had its graces in the 1960s, but they were of the salty, rugged Eastern seaboard flavour. Athletics trumped literature. Blue-collar workaday concerns left little room for arias and poetry. Di Cicco adhered to the social climate, excelling at baseball and lifting weights.

At 15, he found the book The Art of Thinking on a paperback carrel in a grocery store. Written by Voltairian freethinker Ernest Dimnet, it championed the idea of independent thought. “The idea fascinated me,” says Di Cicco. “I had no idea you could have things in your head that would take the place of activities. It started Socratic kinds of dialogue in my head, and got me questioning and getting philosophical.” Shortly after, he stocked up on the poetry of John Keats, Percy Bysshe Shelley and William Wordsworth. He would take his books to the cemetery, sit on the tombstones and read “forever.” In the quiet space, he found solace in his readings, in his philosophical musings, and in his inceptive attempts at writing rhymed verse and sonnets.

The immigrant experience may have amplified his talent for precise nuance and rhythm, says Rita Davies, executive director of the culture division at Toronto City Hall and Di Cicco’s friend since the 1970s. “I share that immigrant experience. And when you’re an immigrant, you learn to – without even noticing it – become extraordinarily sensitive to the signals around you, because you need that for basic survival. Not survival like food and water, but social survival. It’s actually an enormously interesting tool later in life, but Giorgio takes it from being a tool to being an art… he understands the powerful effect of language used with precision and care, and the fine attention to the nuance of the word.”

At 18, Di Cicco left the city of Baltimore behind and moved in with his sister in Toronto. He soon enrolled at Erindale College, immersing himself in the theatre scene. As part of the university’s Poculi Ludique Societas, a group of touring medieval and Renaissance players, Di Cicco performed in plays on campuses across North America. He took on roles in other U of T productions, including Thomas Beckett in T.S. Eliot’s Murder in the Cathedral. “I did so much theatre that I failed,” he says. “I didn’t pay any attention to zoology and botany and whatever else.” After enrolling in University College the following year, he stitched together a curriculum composed entirely of poetry courses. He found particular inspiration in Latin American neo-surrealists such as Pablo Neruda, Rafael Alberti and Cesar Vallejo, admiring them for their ability to “practise a brand of neo-surrealism that wasn’t off-the-wall surrealism, but was grounded in good imagism – imagism that was netted to the subconscious.”

After graduating, Di Cicco continued with his job as a bartender at the Graduate Students’ Union pub. After closing up the bar, he would return to his apartment near Spadina and Bloor, and write poetry until the early morning hours. “On Walmer Road in midtown Toronto, it’s the least noisy time of the day. Three in the morning is just perfect. It’s just nighthawks. Just you and the nighthawks and the typewriter.” A two-finger typist, he would pound out poems on his Olympia typewriter, emptying bottles of eraser fluid. (“Today’s generation can’t comprehend the aggravation of having typewriters and eraser fluid,” he grumbles. “It was a physical, manual labour of love.”)

His poetic output was enormous. After a stint at Books in Canada, where he worked his way up from subscription manager to editor, he soon became one of the few people in Canada making a living from poetry-related activities. Within a few years, he had been published in 200 magazines internationally. Critical Quarterly. Descant. Poetry Australia. Quarry. He wrote his first collection, We Are the Light Turning (1975), in two weeks. He produced enough material for 13 collections of poems in less than a decade. He edited Roman Candles, the first anthology of Italian-Canadian poetry. And then, at the age of 33, he stopped cold. And he wouldn’t publish another poem for 15 years.

***

”First days. I remember continual tears. Tunnels of lightless light. /The invigorating blessed air. The clear and prolonged vistas.” – from “First Days,” Living in Paradise

Who can ever truly know what propels a spiritual quest, far from the world one has always inhabited? All that can ever be glimpsed are shadows, perhaps a line or two of poetry, into a private journey. In 1983, Di Cicco arrived at the door of Marylake, an Augustinian monastery outside of Toronto. A prior named Father Cyril opened the door. Di Cicco asked, Have you got any use for a middle-aged literate like me? The father said, Sure, come on in. Put our library in order and do some dishes and pick up some garbage.

As “the low man on the totem pole,” Di Cicco washed and dried hundreds of dishes daily and served the 30 residents at every meal. He kept the library tidy. He attended community prayers. He acted as a translator for the largely Italian-speaking groups that made pilgrimages to the grounds on Sundays. His room was a brick cell with only a sink, a bed, a desk. From its window, he admired the “lovely view of a little lake behind the monastery, and a lovely little fountain that hardly ever ran, with our Blessed Mother presiding over the blue waters.”

The duties and servitude incumbent on the lowest member in the hierarchy was welcomed by Di Cicco. “It was discipline. And it was in the spirit of service, not in the spirit of ‘my rights are being infringed upon.’ The smaller you made yourself, the closer you felt to God. So the question of rights and dignity was academic or foolish. Spiritual progress often doesn’t rely on rights and questions of autonomy,” he says. “You don’t ask yourself every three minutes whether your sacrifice was worth it.”

Di Cicco’s shift away from a temporal existence allowed him to embrace and explore his fascination with prayer. “It was through language that I discovered prayer. It was through poetry that I rediscovered prayer. I didn’t stop writing poems. I didn’t stop creating. I didn’t stop singing. I just sang in a different direction.”

There was a need for priests within the Augustinian order, so after a year at Marylake, Di Cicco began theological studies at the University of Toronto. He drove down from the monastery every day to attend classes at St. Michael’s and St. Basil’s colleges. In his fourth year of studies, young directors at Marylake began replacing some of the orthodox religious traditions that he loved with more liberal and contemporary practices, so he transferred to the Archdiocese of Toronto. He was ordained to the priesthood in 1993, and began ministering to largely Italian-speaking parishes in nearby Woodbridge and Mississauga.

Today, Di Cicco balances his liturgical duties with professorial and poet laureate obligations. He delivers Sunday sermons at parishes throughout Etobicoke although, when needed, he performs other sacraments: confessions, baptisms, marriages. “Part of why I became a priest was to help people finish the poem of their lives and to help write it with them or they write mine,” he says. “Because the poem on the page wasn’t enough. I wanted the poem on the page and the poem of life to be interconnected.”

At the age of 50, Di Cicco ran into Denis De Klerck, the publisher of Mansfield Press, who persuaded him there was a generation who wanted his poetry back in circulation. Di Cicco produced Living In Paradise (2001), a series of new and collected poems. The collection captures the contours of his poetic journey – and life journey. Throughout his books, there is often a continuous struggle to bridge chasms – whether it is between art and science, the Italian culture of his childhood and the culture of North America, or the intellect and emotion. Indeed, the idea of being caught between two worlds is often a topic that governs their conversations, says his friend Robert Nusca. “You find that idea in biblical writings. Certainly it’s behind St. Augustine’s City of God – the two cities: the city of the world and the city of God, and how people feel themselves caught between these two realities.”

Just as Di Cicco struggles for the incorporation of artistry and citizenry into daily life, he struggles for fusion within his poetry. “Poetry seeks a completion or homecoming…. I’m always getting at something – I think it’s metaphysical. And metaphysical does not mean nonphysical, it means something like heaven and earth coming together, something about disparities merging, something about how the divine is in the earthly, and how the earthly reflects the divine. Something about marrying things. I have this zeal and zest for things to be married.”

Back outside the Italian studies department, Di Cicco is on another break. He lights another Matinée, and reminisces about a time a few years earlier when he travelled to Arizona along Highway 60, using a National Geographic map that a friend had given him. The map was drawn in 1942. Di Cicco got lost. (“Who would have thought the roads in a desert would have changed?” he charges.) With a little help from a gas-station attendant and a new map, Di Cicco found his way through the desert’s silence.

He speaks about how much he loves to travel through deserts: the meditative nature inherent in their landscape; the solitude; the chance for reflection. But then he mentions how much he likes the bright neon cities that often surround them. And yet: the contrast between the garish, corporeal cities of Reno and Vegas and the spiritual, almost godly, desert landscape is so glaring. But yes, of course: This would be the marriage of two worlds. This would be the marriage of heaven and earth.

No Responses to “ Seeking the Divine ”

Thank you for the lovely article about Pier Giorgio Di Cicco. I especially liked the poem "In the Confessional."

Susan Goddard

BA 1965 TRIN, BLS 1966, MLS 1976

Toronto