Under Soviet Union state censorship, publications required the Communist Party’s stamp of approval. But that didn’t stop people from sharing ideas in ways that circumvented the party apparatus – often at great personal risk. From the 1950s to the 1980s, artists and rights activists in particular used samizdat – a low-tech alternative form of publishing, often typewritten and passed from hand to hand – to communicate with each other and spread information.

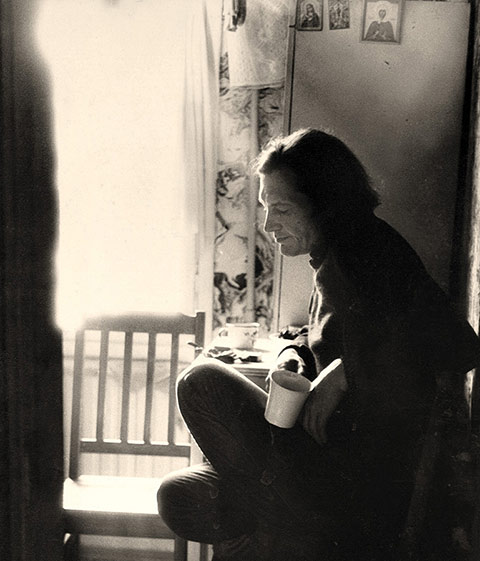

One such artist was Oleg Okhapkin, a religious poet shown above in an undated photo in his kitchen. Ann Komaromi, a professor of comparative literature who has curated the world’s largest digital collection of Soviet samizdat journals (142 issues), says Okhapkin’s writing is interesting partly because he foresaw a return to traditional religious values in Russia following the collapse of communism.

None of these homemade samizdat documents, including Okhapkin’s, reached more than a few hundred people. But some became quite famous. The Chronicle of Current Events documented human rights abuses in the Soviet Union from 1968 to 1982, despite numerous attempts by the KGB to suppress it, and became a major source of unofficial information for readers abroad.

Komaromi is reluctant to ascribe much political clout to the literary and artistic journals in the U of T collection, but she believes they served a vital societal function. “These were alternative communities creating a culture of artistic freedom,” she says. And now they’re available for the world to see.