In September 1901, 19-year-old Elizabeth Bagshaw came to the University of Toronto to register for studies in medicine. She had just arrived in the city the day before from her family farm near Cannington, Ontario. When she entered the registration area, she noticed most of the women were in the line to enrol for arts courses. She joined the queue that was almost entirely men – to register for medicine. One young man tried to redirect her. I’ll stay here, she said. The reaction of the men was one of amused disbelief. “They just laughed,” she said in the National Film Board of Canada movie Doctor Woman: The Life and Times of Dr. Elizabeth Bagshaw.

It was the beginning of a life of defying expectations for Bagshaw who, after earning her medical degree from the University of Toronto in 1905, would set up a successful practice – exceedingly rare for a woman in the early 20th century. She became medical director of Canada’s first and illegal birth control clinic in 1932 and spent more than three decades at the centre empowering women to control their reproductive health and plan the size of their own families.

During her years at U of T, Bagshaw thrived under the challenge of medical school. Many of her classes were held at the Ontario Medical College for Women and she was particularly adept at dissection – her professor praised her proficiency at dissecting cadavers – likely due to her steady, level-headed nature and ambidexterity. She and the other women did, of course, face gender discrimination: classes such as obstetrics and dissection were segregated, teasing from male classmates occurred, and women were pushed into the fields of obstetrics or pediatrics. “I’d [have] liked to have gone through for a surgeon, but in those days there was no chance,” she said in Doctor Woman. “They wouldn’t have trusted a woman in those days to be a surgeon.”

After moving to Hamilton, Ontario, to begin her career, Bagshaw found that maternity work was the mainstay of her practice. Many of her patients were recent immigrants, often Italian, raised in the tradition of midwifery – and this made them much more comfortable with a female doctor. In the early days, Bagshaw rented a horse and buggy from a livery to make house calls during the day; at night, she would bike to homes to deliver babies. So successful was she at maternity work that for three years in a row she signed more birth certificates than any other doctor in Hamilton.

Bagshaw believed informing and helping women in the arena of family planning was the right thing to do – for them and their families

Like every doctor of the time, she also ministered to patients suffering from life-threatening illnesses such as tuberculosis, smallpox and typhoid – in the days before the necessary antibiotics and immunizations existed. Bagshaw herself caught the Spanish flu – which killed tens of millions throughout the world from 1918 to 1920 – but made a full recovery. It was not possible, however, to make a full recovery from her personal losses: In the summer before her final year of medical school, her father had died in an accident on the farm, falling off a ladder and breaking his neck. Then, during the First World War, her suitor, Lou Honey, was killed in the line of duty. Before he had enlisted as a soldier, Honey had given her a diamond ring. He died in 1915. For many years, a picture of him in uniform remained on Bagshaw’s wall.

It was against the hardscrabble backdrop of the Great Depression that Bagshaw’s pioneering work with Canada’s first birth control clinic began. One day in 1932, a woman named Mary Hawkins paid a visit to her office. Hawkins – who did much volunteer work with women and children – had opened the clinic on March 3, 1932, to offer contraceptives and information on family planning. However, the doctor they hired resigned three weeks in, and Hawkins had come to implore Bagshaw to sign on as medical director.

The stakes for those involved in the clinic were extremely high: It was an indictable offence – liable to two years in prison – to sell or advertise contraceptives or to instruct people on how to use them. One clause in the code offered hope: if one could prove “public good” was served by their actions, they could avoid conviction. But no one wanted to be put in the position of a long, expensive trial or risk being jailed.

Bagshaw initially turned down the position of medical director. It was not out of legal concerns: She was not one to back away from a fight. But she was time-constrained as a doctor with a thriving practice and a young adopted son to raise.

Then, she changed her mind. As a physician, she had borne witness to the hardships that many large families faced, and the physical problems women suffered from bearing many children. Now, in addition, there was the relentless poverty caused by the Great Depression: husbands on relief, great numbers of children that couldn’t be fed or cared for. In the 1930s, the maternal death rate in Canada was high. Many women also died trying to perform abortions on themselves, or while undergoing the procedure illegally. Bagshaw believed informing and helping women in the arena of family planning was the right thing to do – for them and their families. “I had so many patients who were having babies nearly every year or two years, and their husbands were out of work, and they hadn’t enough to eat. Why should they go on having more children?” she said, pragmatically, in the book Elizabeth Bagshaw, by Marjorie Wild.

And so, almost every Friday afternoon for the next 34 years, Bagshaw would work in the clinic: She would fit women for diaphragms, instruct them on the proper use and then have them come in for a followup. She did not receive a salary – only a small honorarium fluctuating between $100 and $200 a year. The number of women who sought her help was well beyond the clinic’s predictions: In the first year, they expected about 60 women. Almost 400 came.

In retrospect, this likely didn’t shock them. The clinic provided the first opportunity most women ever had to learn about their own bodies and control their reproductive destinies. Prior to the clinic, men were the gatekeepers to women’s health in Canada. Men headed the educational and medical systems that controlled knowledge about birth control. They helmed the pulpits that made the religious creeds against using contraceptives. They ran the courts that judged birth control as unlawful, and spoke loudest in the court of public opinion that deemed it immoral. The women who ran the clinic cut through this socially constructed shame, countering that birth control was “about as immoral as a good day’s washing is immoral.”

“The challenges that [Bagshaw] faced during the Depression are similar to challenges that doctors in many countries face today, whether it is in countries where bias against women prevails or in countries where sexuality is not understood as a natural and important part of life,” says U of T’s Rebecca Cook, professor emerita of law and co-director of the Reproductive and Sexual Health Law Program. “Her legacy continues to motivate doctors today. She understood that neglecting health care that only women need contributes to their subordination.”

One of the clinic’s staunchest opposers was the Roman Catholic Church. Bishop J.T. McNally of Hamilton incessantly attacked Hawkins and Bagshaw on the pulpit, referring to them as “devils and whores,” and birth control policies as “blasphemous, degrading, dehumanizing.”

“The bishop always warned the [nursing] graduates not to come near the [clinic] because it was run by heretics and devils,” said Bagshaw in Doctor Woman. “I was the devil. I didn’t worry about it.”

“It was the best advertising we had,” she added. “It was against the law to advertise, therefore we couldn’t say anything, but he advertised it – then I’d tell the nurses, ‘Be sure to be on time, don’t be late at the next two or three clinics because we’ll have a number of Roman Catholics there.’ And we always did.”

And then in September 1936, a trial brought the issue of the legality of distributing and advising on birth control to a head. Dorothea Palmer, a nurse with the Parents’ Information Bureau in Ottawa, was charged with advertising birth control after visiting women in their homes to teach them about family planning. After a tense 20 days of trial, a verdict was reached: she was not guilty. The magistrate found that Palmer had, indeed, acted for the “public good.” The case was appealed. She won again.

After that, the most stressful, worrisome years were over for the clinic. The fear of being charged or imprisoned had dissipated. But it wasn’t until 1969 – three years after Bagshaw retired from the clinic, that the birth control law was officially changed.

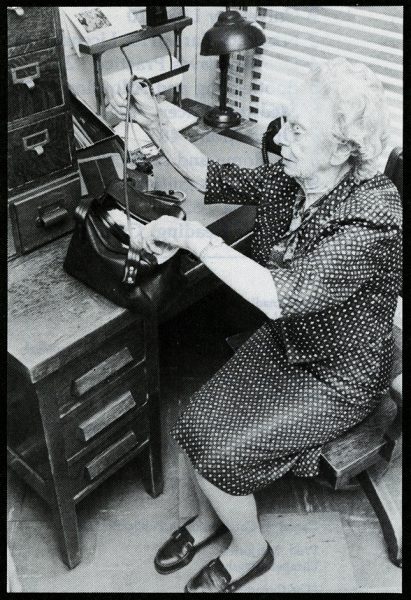

Bagshaw didn’t retire from her own practice until the age of 95 in 1976, which made her the oldest physician practising in Canada. (At that time, she had about 50 patients all over the age of 80.) She died at the age of 100. For her pioneering work, she had been inducted into the Canadian Medical Hall of Fame, invested into the Order of Canada and had an elementary school in Hamilton named in her honour. Bagshaw had greatly advanced the concept of health-care equality: that regardless of what opinions one held, society was not entitled to impose them in a way that impeded the health of another. “In addition to her courage in facing prejudice and stigma, her work contributed to our understanding of health equity. She understood that health-care services need to be provided in an equitable way to all women, in a way that attends to their sex-specific health-care needs,” says Cook. “Now, international human rights law recognizes that for women to be equal, in fact, their sex-specific health-care needs have to be accommodated.”

No Responses to “ Doing the Devil’s Work ”

I particularly liked writer Stacey Gibson's phrase, "the women who ran the clinic cut through the socially constructed shame."

Here are a few lines from a poem composed in 1691 as an answer to another Roman Catholic bishop, in colonial Mexico:

Listless of wing and song

Scarcely heard, even more dimly sensed,

Disgraced Nictimine lurks

In the crevices of sacred doors

Or the most promising gaps in the high window,

Seeking surreptitious breach.

Perpetrating her sacrilegious aim

To extinguish and defile the glowing sanctuary lamps

That hold the sacred flame

And gulp the clear thick oil

Sweated, forcibly surrendered in the olive press

From the fruit of Minerva's tree.

Nictimine was blamed for incest by the culprit, her father. Initially ashamed, she fights back seeking escape, revenge and another path to truth under the aegis of the pagan goddess.

This passage from a poem called "Dream," was written by Sor Juana (I did the translation) in defence of women's right to learn, to write and to tell their truth. The Mexican Clergy hounded her with threats of the Inquisition.

What an amazing story!

Wonderful article. I love her "damn the torpedoes" attitude. I wonder how she would respond to the rise of these same old barbaric ideas today.

Dr. Elizabeth Bagshaw came to my grandfather's home on Bay Street North, in Hamilton, Ontario, usually on her bicycle, to tend to the family. I remember her caring concern. It must have been in the 1930s.

In the 1980s, I taught at Elizabeth Bagshaw School when it was located in the east end of the city, on Albright Rd. Years later, after Dr. Bagshaw retired and moved to First Place, a C.G.I.T group of young girls from St.John United Church were conducting a Christmas service at First Place. There in the front row was Dr Bagshaw. I was so thrilled to see her again. She remembered our family fondly. She certainly was a woman to remember -- and to honour.

Thank you, Stacey Gibson, for your integrity and valour in writing this article. It needs to be told time and again today, since we seem to be regressing to the ethics of when Elizabeth Bagshaw first appeared at U of T. I had the honour of being one of the music teachers at the school named for her in East Hamilton. We knew Dr. Bagshaw and had her visit the school several times. We even honoured her birthday with a special concert. I have several pictures of that evening in my box of treasured memories. During our chats together she relayed many of the details that were included in this article. Keep up the good work. It is by standing on the shoulders of giants such as the fearless Dr. Bagshaw that we move in the direction of goodness.

Loved this article! As a long-time proponent for women to have control over reproduction, I believe this is an important story to share. Dr. Bagshaw is a true inspiration.

Thank you for memorializing a great human being who happened to be a woman, who happened to be a Canadian. I think she and Norman Bethune would have been good friends and allies.

I had to laugh when I read her comment that the strident opposition of the bishop and the Roman Catholic Church made for good advertising. What a courageous, wonderful woman!

What an incredible story!

What a splendid article. Thanks for bringing this exceptional person to our attention.

What a remarkably brave pioneer of a doctor! She flew in the face of both organized religion and the law, knowing that she and her cause were right and just -- and that the authorities were wrong.

This is a wonderful article. These words should be repeated everywhere and often: "that regardless of what opinions one held, society was not entitled to impose them in a way that impeded the health of another." I'm thinking in particular of the United States, which has demonized Planned Parenthood and effectively banned abortion in some places -- even in cases of rape. The reach of the Catholic Church, even in these secular times, is long and lasting.

Thank you very much for the article. I am in awe of this great human being. Her services were priceless. Canadian women are indebted to her.

A remarkable story of a remarkable woman. Just think of the learning experience if student nurses had been allowed to attend the clinic. Of course some of us were students in the distant past.The revisions to American law in the Trump era are appalling.

I am the medical director of the oldest abortion clinic in Vancouver -- the Elizabeth Bagshaw women’s clinic. I never knew this history. Did you know about our clinic? This is truly an amazing story of an incredible woman. She’s a hero.

What a remarkable woman. So dedicated and so needed at that time.

The Women's Canadian Club of Hamilton, Ontario, is honouring Dr. Elizabeth Bagshaw at a luncheon on October 9th. At the same time, we are introducing our 'Women of Spirit' award to a deserving Hamiltonian who embodies the spirit of Dr. Bagshaw. We would love to display your article.

Details of the luncheon can be found on our website at wcchamilton.ca.

Thank you for a wonderfully written article.

Dr. Elizabeth Bagshaw did a wonderful job for the world's women. If her soul can hear me, I salute her from the bottom of my heart. And Stacey Gibson did an amazing job writing this article.