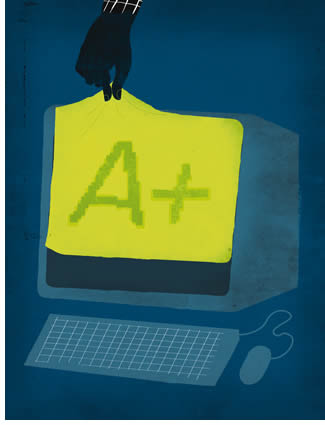

Teaching Assistant Paul Filipiuk was almost certain that a student in one of his cinema studies courses last year had plagiarized her essay. But he couldn’t prove it.

“It was so obvious that she had gotten somebody else to write this for her. Her written exam was of the quality you’d expect of an undergraduate, but this paper read like it had been written by a PhD candidate,” he says. “It was just way, way too good.”

Filipiuk and the course professor searched the Internet for uncredited sources of the student’s work but came up empty handed. The professor confronted the student, but she denied any wrongdoing. Since neither Filipiuk nor the professor could prove otherwise, they were forced to award the student a high mark. “It’s very hard to prove a charge of plagiarism unless it is absolutely cut and dried,” says Filipiuk.

Instances of academic misconduct are still rare at U of T, but have been growing in frequency for reasons that elude instructors and administrators. Some blame the abolition of Grade 13 in Ontario for leaving first-year students less well prepared for university and unaware of what constitutes plagiarism. Others say the Internet makes it too easy for students to cut and paste text into essays. Some believe that cheating is actually no more common than before, but instructors are more vigilant, leading to a greater number of students being caught.

There is no shortage of statistics about academic dishonesty, but views diverge on what the figures mean. In a widely reported University of Guelph study of more than 13,000 undergraduates at Canadian universities, which was conducted in 2006, slightly more than half of respondents admitted to having cheated on written work.

Professor Edith Hillan, U of T’s vice-provost in charge of academic matters, cautions against attaching much significance to the Guelph study because it drew responses from between just five and 25 per cent of the student population at the universities surveyed. The modest response rate prompted the study’s authors to state, “This study should not be used to make definitive claims about the state of academic misconduct within Canada, but rather as indicators of potential areas of concern and action.”

At U of T, the number of official cases of plagiarism climbed to 403 in 2005-06 from 92 a dozen years earlier. Hillan notes that this increase coincides with an almost 50 per cent increase in enrolment. When measured against the total student population, just 0.6 per cent of students are caught cheating each year. That’s still high in historical terms, but not as alarming a problem as the Guelph study suggests.

Geography professor Sarah Wakefield believes that many students accused of plagiarism don’t even realize they’ve done anything wrong – a situation she blames partly on the Internet. “When you used to have to write down notes from books by hand, you usually wouldn’t write the quote down verbatim,” she says. “Now it’s much easier to just cut and paste text than it is to paraphrase it.” Wakefield also says that first-year students can be unaware that they should not copy even a single sentence from a source.

Like many U of T professors, Wakefield has begun using the website turnitin.com to help detect plagiarism in student essays. Turnitin.com allows instructors to check student work against millions of previously submitted essays stored in its vast databases. The site also checks student work against more than five billion web pages. “The software makes it much easier to show students how a particular sentence comes from a particular website,” says Wakefield. “It’s interesting to see the moment of transformation, when the penny drops and they realize what they’ve done wrong.”

Researchers at University of California, Berkeley, created turnitin.com in 1994 to catch students who submitted their own work in more than one class or handed in another student’s essay as their own. Two years later, the researchers formed a company, iParadigms, to license turnitin.com to other academic institutions. The company later expanded the software to identify material copied from the Internet. Thousands of institutions in more than 100 countries, including 45 colleges and universities in Canada, now use turnitin.com.

Turnitin.com doesn’t deliver a simple “yes or no” verdict on whether a work has been plagiarized. Instead, its “originality checking service” scans the text and scores it for similarity against everything in its database, granting each paper a percentage to indicate originality. It highlights text that appears in its database and flags quotations, even if they’re properly cited. Instructors use their judgment to determine if a student has plagiarized a work, quoted a passage without proper citation or coincidentally written sentences that resemble passages from turnitin.com’s database.

U of T licenses turnitin.com and encourages – but does not require – its professors to use it. Under university policy, professors can ask students to voluntarily submit their work to the website. (Professors create accounts for their courses at turnitin.com. Students establish a password-protected profile through which they can upload essays and other work.) Students who object to using the site can prove the originality of their work in other ways, such as by submitting a series of rough drafts. Approximately 500 U of T faculty members, or about one-fifth of the total, use the site.

Adrienne Hood, associate chair of the history department, has used turnitin.com in her undergraduate classes since 2005, and in that time hasn’t caught a single student plagiarizing. In her view, the site acts as a deterrent. At the beginning of each term, she tells students why she uses turnitin.com and explains the difference between direct quotation and paraphrasing, how to properly cite sources and the importance of academic integrity. “First-year students especially aren’t always clear on this,” she says. Hood also suggests that students read about essay writing on U of T’s website, or visit one of the university’s writing centres to have their skills assessed. She also warns that U of T considers plagiarism a serious offence. Penalties for academic dishonesty range from a mark of zero (on a small assignment for a first-time offender) to expulsion (for a student who has previously been convicted under U of T’s academic code).

Hood reports that none of her students have objected to her using turnitin.com. “It evens the playing field,” she says. “Students like knowing they aren’t competing with those who just lift text from the Internet, for example. This doesn’t replace judgment, or my need to read and grade the paper carefully. But I don’t have to chase down and check citations, trying to assess what is original. This allows me to spend more time giving feedback and, ultimately, to teach better.”

Pam Gravestock, associate director of U of T’s Office of Teaching Advancement, has also encountered few student complaints about turnitin.com. “In the six years that U of T has licensed it, I have been informed of only a handful of students who have outright refused to use it,” she says.

Of the students who oppose the use of turnitin.com, many do so for reasons that have little to do with plagiarism. Dave Scrivener, a fourth-year Canadian Studies and anthropology student and vice-president of external affairs for the University of Toronto Students Union, has been a vociferous objector. He has argued that because turnitin.com is an American company, essays submitted to the site could fall under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Patriot Act – controversial legislation enacted after 9-11 that gives the American government unprecedented access to private information. He says that the American government could, hypothetically, scan turnitin.com’s database for words such as “bomb” and “jihad” and then criminally investigate the students who submitted papers with these words.

iParadigms recently responded to Canadian universities’ concerns about turnitin.com’s requirements under the Patriot Act by creating a separate server to store Canadian essays. It hired Digital Days, a Montreal IT company, to maintain the server.

Students at U of T and on other Canadian campuses have also raised concerns over turnitin.com’s copyright practices. Terry Buckland, the executive assistant of the Arts and Science Students’ Union at U of T, questions whether turnitin.com has the right to compile a database of student works without paying the students royalties. “Professors and graduate students wouldn’t want their own material hijacked, and I don’t think undergraduates should be treated any differently,” he says.

Turnitin.com hired the Canadian law firm Miller Thomson to investigate copyright concerns. The firm concluded that the website does not violate student intellectual property rights. “In essence, uploading an electronic copy of an essay to Turnitin is no different than a student submitting a hard copy to the instructor in class,” says Gravestock.

Along with some students, there are others who would prefer not to use the service. English professor Nick Mount opposes using turnitin.com on philosophical grounds. He calls it “one more step” into the virtual classroom. “Technology is distancing us ever further and further from our students. At what point will society ask, ‘What do we really need universities for if we can just do all this online?’”

Mount has chosen not to use turnitin.com. Instead, at the beginning of the year, he assigns an in-class essay to assess how well each student writes. If he sees a passage in a subsequent paper that strikes him as suspiciously different from the student’s previous writing, he Googles it. “If a student can find the material online, so can I,” he says. In 10 years of teaching (seven at U of T and three at King’s College in Halifax), Mount has discovered between 30 and 40 cases of plagiarism.

Most professors find it extremely difficult to confront a student about plagiarism; it can emotionally devastate the student. “Accusing somebody of intellectual dishonesty is never a pleasant experience,” says Mount. “They are always tremendously distraught. I keep a box of Kleenex in my desk for those occasions. But what propels me is the sense that if I don’t go through with it, it devalues the achievements of other students.

“You can’t make the world a perfect place through software. And I can’t be responsible for the ethical development of my students. Some will always want to cheat. But most students cheat when they are bored and scared – it is my job as a teacher to make sure they are not bored and scared. It’s my job to motivate them. And if I’m supposed to treat my students as adults, and let them know that I am interested in what they have to say, using this software makes it much harder to tell them that I respect their ideas.”

Regardless of whether professors choose to use turnitin.com, the message from U of T administrators is clear: for the sake of the vast majority of students who play by the rules, plagiarism will not be tolerated. The university will also strive to ensure that students know what’s expected of them. “We take academic integrity very seriously. It is central to everything that we do,” says Hillan. “We need to make sure from an institutional perspective that our teaching and research are of the highest quality. If problems are uncovered, we can’t just brush them under the carpet.

“But we don’t just deal with problems once they occur; we also take a proactive approach. It’s ultimately about trying to prevent misconduct in the first place.”

Zoe Cormier (BSc 2005 Victoria) is a writer who recently moved from Toronto to London, England.

No Responses to “ Stolen Words ”

This article, which dealt primarily with arts courses, brought to mind my experience as a teaching assistant for nine years at U of T. During that time, I tutored classes and graded papers in the sciences – psychology, physiology and math – and found no shortage of students cheating. However, when my fellow TAs and I brought these acts to the attention of the course professors, the students generally received no worse a penalty than a grade of zero on the assignment. Harsher penalties and personal confrontations were avoided and the incidents were not reported to higher authorities, presumably because the professors themselves feared a stain upon their reputations.

The cheating my fellow TAs and I discovered included copying assignments from previous years, submitting identical math proofs or laboratory measurements (which rarely occurs when students work independently) and sharing information during examinations. When TAs reported these incidents to the professors, we were, by and large, ignored. If U of T wants to catch academic malefactors, it is the faculty, not the students, who need ethical training – and the assurance that they will not be held responsible for incidents that are beyond their control. Without that, all the software in the world won’t make a difference.

Ifty Nizami

BSc 1982, MSc 1988, PHD 1999

Decatur, Georgia

Ifty Nizami and his fellow scientists might benefit from knowing how we have traditionally dealt with plagiarism in the humanities.

Pupil: Sir, you gave my paper a D.

Tutor: Well, Bloggins?

Pupil: Sir, Snokes told me that when he submitted this identical paper last year, you gave it a C.

Tutor: My dear Bloggins, you’re not allowing for depreciation.

William Cooke

BA 1968 Trinity

Toronto

As an alumna and manager of the Office of Student Academic Integrity at the Faculty of Arts and Science, I was pleased to see the issue of Internet plagiarism — a critical one faced by the academic community today — featured in “Stolen Words."

Our office is responsible for resolving allegations of academic misconduct at the Faculty of Arts and Science, and advising departments and programs on the resolution of offences. I would like to clarify that the article’s first example, a departmentally resolved case where the purchase of a paper was strongly suspected but unproven, resulting in a “high mark” for the student, is not typical.

Allegations of purchased papers, or papers where the plagiarism is not “cut and dried,” are admittedly challenging to resolve, but the prognosis for these cases is far from hopeless. Even though an instructor may initially be unable to prove that an offence has occurred, help with the investigation is available at the divisional level. The Office of Student Academic Integrity successfully resolves offences involving purchased papers every year, sanctioning students with a failure in the course and usually a suspension from the university for up to one year.

The efforts of faculty and staff to promote academic integrity and report offences when they occur are integral to encouraging proper academic behaviour among students and to maintaining the university’s strong ethical reputation.

Kristi Gourlay

BA 1993, PhD 2002

Toronto

This article and comments certainly resonated with my own experience as a professor at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education (OISE) from 1986 to 2007. Like Ifty Nizami, I found higher levels of the university administration generally reluctant to pursue cases of plagiarism. With one notable exception, where the administration followed the plagiarism policy to the letter, the general tendency was to provide excuses for the student and to discourage me from pursuing the case.

I was told, for example, that one student "didn't really mean to plagiarize" (a case in which the student had copied an entire paper verbatim from the Internet). In another instance I was warned that the student could sue me. It was not clear to me how, since I was telling the truth and could back up my position with thorough documentation.

A university degree is devalued when administrators hold the view that a dishonest student "isn't going to fly a plane or do brain surgery so where's the harm in granting the degree?" Apart from the obvious answer, this attitude is an affront to the students who earn their degrees honestly, on their own merit.

Helen Jefferson Lenskyj

BA 1977 Woodsworth, MA 1981 OISE, PhD 1983 OISE

Professor Emerita, OISE

Toronto

As a student charged with academic offense, I only have one thing to say. "It's very simplistic to think that academic offenses take place because students are too lazy or not responsible."

Not to say that there's no personal responsibility, but look at the unfair structure of our education system that put students under tremendous financial pressure, bad job prospects, and lack of enough tutorials and office hours because of low budget.

In addition, most penalties given by the administration is not proportionate to the offense and usually over-punish students.

It's funny to hear TAs complaining about profs not taking academic offenses more seriously: calm yourselves. Just because you are under intense scrutiny in trying to prove your thesis doesn't mean that every undergraduate student should be considered cheaters. Stop taking your stress out on lowly students, and remember what it's like to have to cram a full course load into a week (on top of work, because, unlike you, we are not paid to study). Spend more time teaching students how to ensure they don't plagiarize instead of releasing your stress onto them.