A Lifeline for an Endangered Language

U of T linguists have partnered with an Indigenous community member to bring the Munsee dialect back from the brink of extinction Read More

The Delaware Nation, a community of about 550 in southwestern Ontario, is one of the oldest settlements in the region. But most members of the long-standing community are no longer able to converse in the language of their ancestors. Today, there is just one person who can fluently speak the Munsee dialect of the Lunaapeew language – Dianne Snake, and she is in her 80s.

The dialect, which is part of the Algonquin family, is one of dozens of endangered Indigenous languages in Canada.

Bruce Stonefish, a member of the Delaware Nation, fears that losing the language would permanently close a window onto how his ancestors lived and their worldview. “Our language was conceived in the way that we smell, taste, see, feel, hear, and in the way we experience creation,” he says. The Munsee word for “dog,” for example, is mwáakaneew, which roughly translates to “one who is always ready.” As Stonefish explains, “this conveys our relationship with the dog and how, at our side, they’ve helped us stay alert.”

Stonefish recalls picking up a few Munsee words and phrases at an early age, though his parents didn’t speak it, and learning more in his early 20s as part of a cultural program taught by Snake. Throughout his life, he says, he has felt motivated by a sense of personal duty to help preserve the dialect. Now, he is working with Juvénal Ndayiragije (Ndah-yee-RAH-gwee-jay), an associate professor of linguistics at U of T Scarborough and the chair of the department of language studies, to do just that.

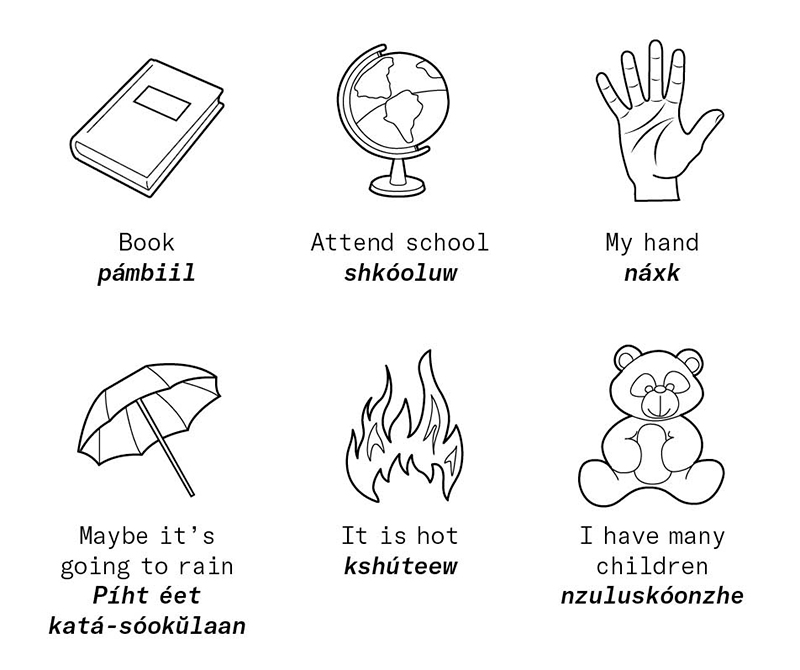

Ndayiragije and his research team have developed an online tool they think could help save Munsee and other critically endangered languages in Canada and around the world. The tool, which they are testing with Ojibwe (also an Algonquin language), contains 378 English sentences that were meticulously constructed to capture most of a language’s grammatical elements.

The researchers enlisted primary speakers of Ojibwe to translate the 378 sentences and then read them aloud in Ojibwe. Then they saved the audio recordings to a database. Having almost completed the data collection for Ojibwe, the researchers recruited a Delaware tribal council member from Oklahoma who speaks Unami, a dialect closely related to Munsee, to translate the sentences into Unami and then read them aloud. Eventually, by creating a language database of the two dialects, as well as Ojibwe, the researchers will be able to conduct a comparative analysis. “It may end up being similar to comparing two dialects of German with English,” Ndayiragije says.

Meanwhile, the research team is using the knowledge they’ve collected to develop online teaching and learning tools that will enable people to learn Ojibwe from scratch. Once they have proof that the concept works, they’ll expand to Munsee and other languages. Under the guidance of Jed Meltzer, a psychology professor who specializes in language processing, and Safieh Moghaddam, an assistant professor of linguistics at U of T Scarborough, the online tools are designed to use “spaced repetition.” Users start with simple words and grammatical concepts, repeating them often at first and then less frequently as they progress through the lessons.

Meltzer, who is also a senior neurorehabilitation scientist at Baycrest Health Sciences, compares the program to digital flashcards. “If you know a word well, you’ll remove it from your deck of flashcards and focus on the ones you’re struggling with,” he says. “The program does that as well, and through memorization, helps you build up the skill over time.”

The researchers are still verifying the accuracy of the program they built for Ojibwe learners, but Ndayiragije feels confident that, with Stonefish’s assistance as an advanced speaker of the Munsee language, the online tools will prove useful to help revitalize it as well. The team is also developing course materials to help train language teachers. “The goal is to empower community members to take the lead on revitalizing their own languages,” he says.

For his part, Stonefish, who has helped create a dictionary of Munsee words, has his doubts about relying solely on technology to revitalize a language. He believes supplementing online tools with cultural teachings is important, especially for a language such as Munsee that is largely based on oral traditions. Indigenous Elders and Knowledge Keepers who speak the language and understand the traditional translations are an essential part of the process, he says.

Yet Stonefish remains hopeful that the tools being developed at U of T Scarborough will work well in tandem with the Elders’ cultural teachings. “I am excited for the technology and think it’s a really good start,” he says. “But I want to honour the language by recognizing the spiritual connection within it.”

No Responses to “ A Lifeline for an Endangered Language ”

Very sadly, about a month after this article appeared, Bruce Stonefish very suddenly passed away from this world.

Juvénal Ndayiragije writes:

I am saddened to hear about Bruce’s sudden passing. I knew that he was going through health challenges but his picture here gave me hope. Now he’s gone!

As the old African proverb goes: “An elder who passes away is like a library that burns.” We lost a great man and a dedicated ally in preserving Munsee. The future of our project is uncertain without him. Yet, we won’t give up.

I am very interested in your attempt to preserve this Indigenous language. It would be a terrible shame to allow these languages to become extinct. Surely, current technology could be used to record and preserve translations. Saving this important part of world culture and history would be a huge benefit for our descendants.