Learning to Think –

or Learning to Prompt?

As AI reshapes what’s possible, 10 U of T students reflect on what university is for Read More

At a moment when some are questioning the value of a university education, we asked students across U of T’s three campuses what higher learning means to them. What followed was a candid, wide-ranging conversation about careers, critical thinking, AI and the uneasy sense that the future is arriving faster than anyone expected.

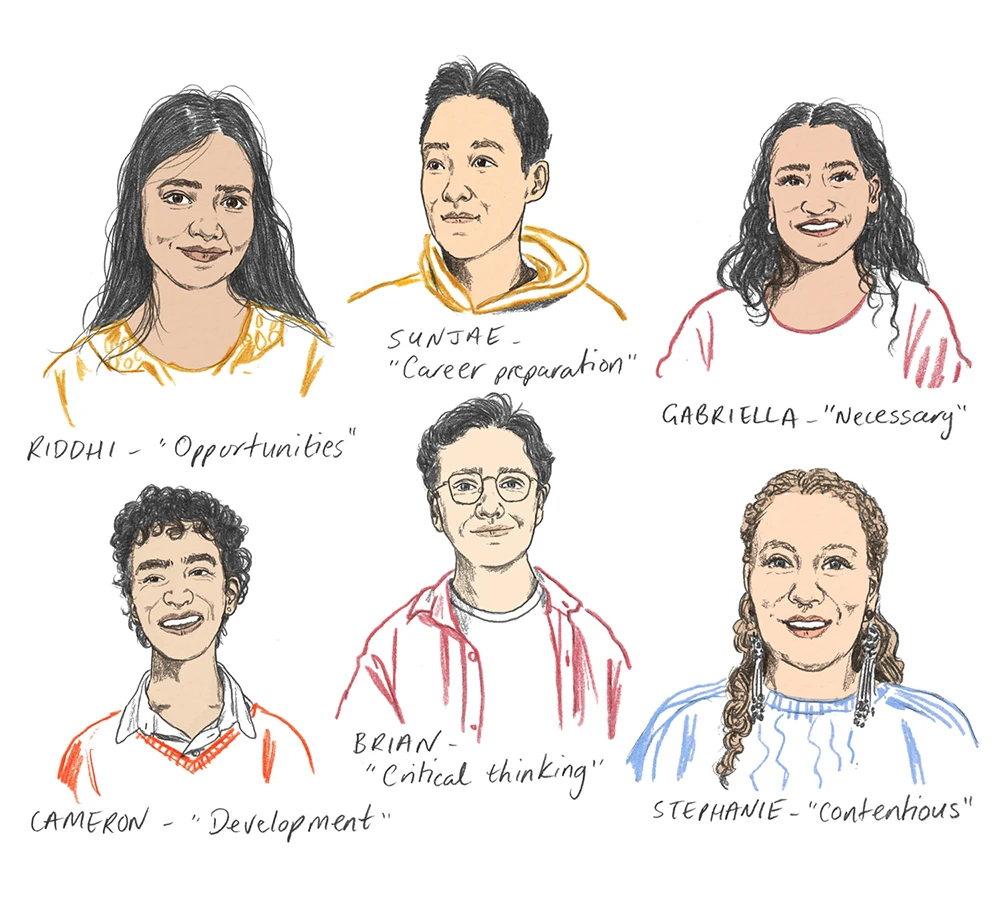

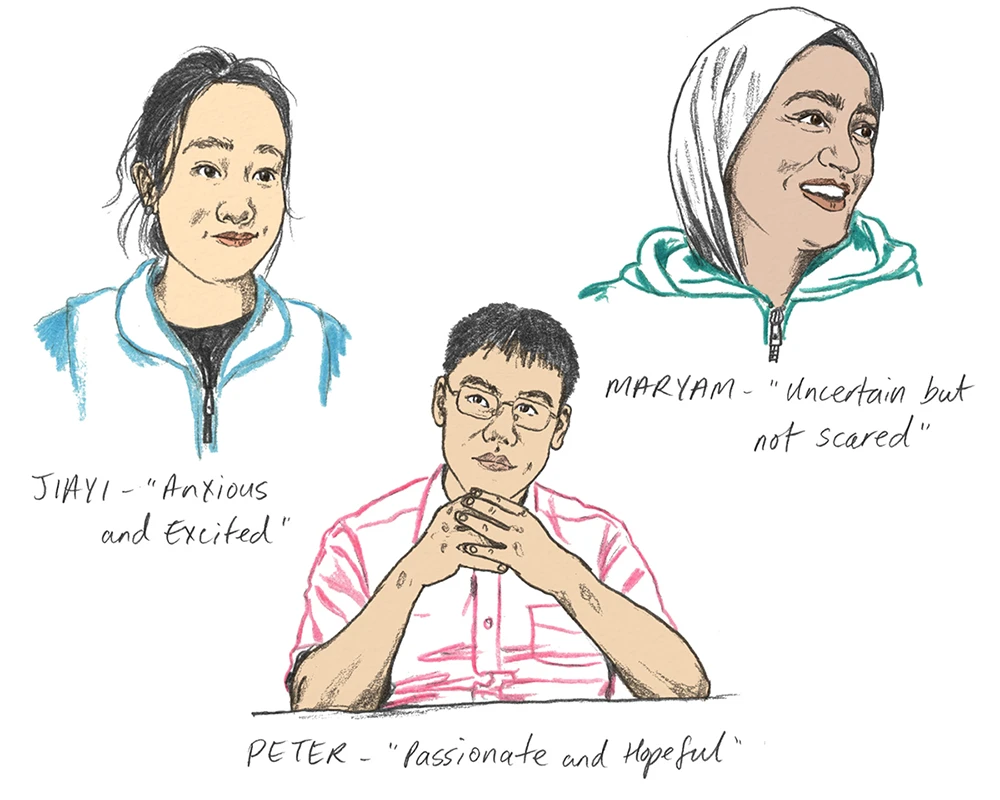

What does “university” mean to you now – in a word or phrase?

Gabriella (Second-year, political science, public policy and urban studies): Necessary. I don’t think university is necessary for everyone, but I think the possibility of having a university education is necessary – for many different career paths and for further education.

Stephanie (PhD, adult education and community development): Contentious – in the sense of who does and does not have access to university, what gets studied here, and the ideas that emerge from university that the public may or may not accept.

Brian (Second-year, math and economics): Critical thinking. The main takeaway from university should be to understand where the ideas you’re being taught come from. This can only happen by thinking critically.

How has your understanding of university changed since you arrived at U of T?

Jiayi (Third-year, information): I initially saw university as being about learning. Learning is important, but I’ve realized that just as important are the people you meet, the opportunities you pursue and the extracurriculars you engage in.

Maryam (Second-year, accounting): Before I started, I thought, ‘I’ll get a degree and life will settle itself.’ But anyone can get a degree. It doesn’t make you any better than anyone else with that same degree. The network you make and the opportunities you take on are what make your university experience different from everyone else’s. A degree seems like the bare minimum now – it’s what you do in addition that makes you stand out.

Riddhi (Third year, computer science and business): My perception has shifted from seeking a strictly qualification-based education to seeking ways to better understand myself, my environment and what I want to do in the future.

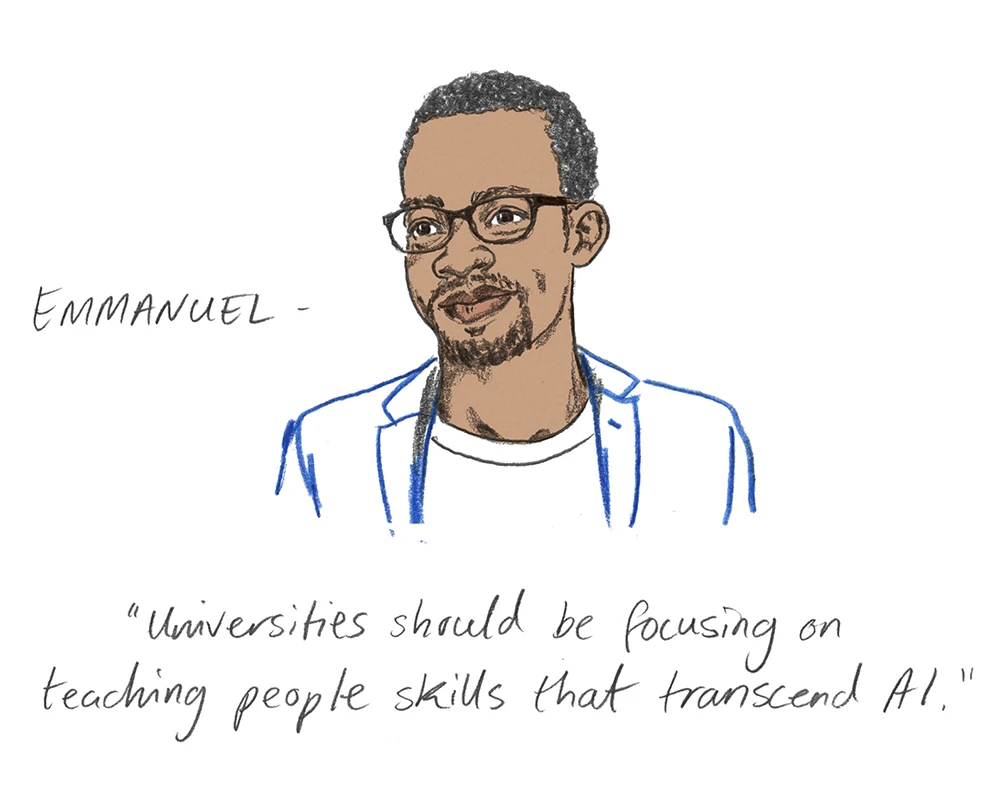

Emmanuel (PhD, environmental science): My university experience has reinforced that there’s more to the world than what we discuss in classrooms. Through my involvement with the Lawson Climate Institute, I met a member of Prime Minister Mark Carney’s cabinet. She told me one of her biggest day-to-day problems is translating policy decisions into an economic case for the country. In my classrooms, we talk about climate change and carbon emissions, without necessarily addressing economic implications. It’s always eye-opening to speak with someone at the cutting-edge of policymaking.

As some of you have noted, career preparation is part of the picture. What else should a university be for?

Cameron (PhD, English): I think about this a lot because studying English is less practical than learning science, technology or business. For me, university is not just about gaining qualifications for a job – you get to pursue something you love. Over-emphasizing practicality can marginalize degrees that are not practical. The arts and humanities may not teach you a particular skill, like how to code or use Excel or how to think about the stock market, but they teach you how to think critically, how to grow as a person and how to approach something new.

Stephanie: There’s more to university in other ways, too. You may not know your career path yet, but you can leverage university to connect with communities outside campus that you wouldn’t otherwise have access to.

Riddhi: As an international student, I had to consider huge trade-offs – higher fees, greater distance. So, for me, university is about more than educating myself. Arguably, you can do that from online courses. Coming to U of T has broadened my horizons. At U of T Mississauga’s International Education Centre, I meet international students from many different backgrounds, with different mindsets. They help me break down my own strongly held views, listen to other perspectives and form new ideas.

Emmanuel: I don’t think I’d be where I am today, if not for university. University has given me a platform to learn and fail and grow. As much as we say universities are expensive, as a Black student, I think they are one of the most cost-effective ways to build equity in society – in ways the private sector cannot do.

Peter (Fourth-year, economics and psychology): University doesn’t necessarily prepare you for a specific job. That’s what a trade school or a community college does. In many careers, you learn the skills when you actually do the job. What a university education provides is the credential – a signal to employers that you can work independently, manage your time and learn effectively.

What have you gained here that goes beyond a credential – that doesn’t show up on a transcript?

Emmanuel: University provides an encouraging, low-stakes platform to develop skills. A job is high stakes – you don’t get to fail as freely. Here, you can make mistakes. You can fail at things like writing a report. Employers don’t have time for that.

Gabriella: I needed to learn how to be willing to embarrass myself, to slip up. I struggled with that in first year because I was nervous about saying the wrong thing and people thinking I wasn’t qualified to be here.

Brian: Many first-year students feel they need to impress people. But this undermines learning and can lead to perfectionism – a kind of paralysis where you think, ‘It won’t be perfect, so why bother.’ You need to embrace the mindset of ‘do it – even if it’s bad.’

Cameron: Last term, as a teaching assistant, I had students tell me they use ChatGPT, during class sometimes, because they don’t want to be embarrassed by being wrong. This is so frustrating because in English there are no right answers! You’re refining your critical thinking. I worry that if students become over-reliant on AI tools, they’ll not learn from their mistakes.

As AI accelerates change, how is it shaping how you feel about your career – and the future more generally?

Brian: The idea of a supercomputer that can answer all our questions and take care of everything for us concerns me and makes me think of the movie WALL-E. Will I even have a job 10 to 15 years from now?

Emmanuel: I feel uncertain, a little anxious. PhD grads often want to get into academia, industry or policy advising. The job market has always been competitive, but AI is a threat multiplier. It compounds that anxiety. I ask myself whether my PhD is incentivizing me to learn skills that make me indispensable, or am I learning skills that AI will be able to do?

Maryam: I’m uncertain but not scared. I want to become a chartered professional accountant, and I believe that we will always need people with accreditation. A few months ago, a major accounting firm messed up an audit badly – mostly for using AI and not having a human supervising. The public is not going to trust AI. They’re not going to trust AI with their company’s profits, with their own health or to perform surgery on them. They want a person who has a licence or designation and can show they know what they’re doing.

Peter: I feel passionate, hopeful and cautiously optimistic. I think AI will replace some jobs, but new jobs for humans requiring high skills and intelligence will open up. As young people, we need to stay informed about AI and adapt. False optimism that AI “will not replace my work” is not a smart strategy.

Looking ahead, which skills do you think will be essential? Which ones are you trying to build now?

Gabriella: Anything that is innately human – like people skills, critical thinking skills.

Riddhi: One of my role models is Leena Nair, the CEO of Chanel. She’s commented that corporate leadership is shifting from hand to head and now to heart. We can complement AI by bringing our human perspectives into play.

Jiayi: The ability to leverage data in your work. Every industry will use AI to increase productivity. You will need to maintain your human qualities but also gain practical AI skills.

Stephanie: Resiliency will be important – being able to adapt to spaces, workplaces and industries.

Sunjae (Second-year, international development studies and economics): The ability to discern truth from misinformation will be critical as AI develops.

Emmanuel: I’d say there are at least three skill sets we need for the future: being AI-savvy; being adaptable, resilient and open-minded; and those deep, human abilities such as listening, critical thinking, making partnerships, cutting through red tape, working collaboratively – non-technical skills that are outside the realm of digital technology.

How are you actually using AI?

Cameron: I have never used AI and I’m proud of it. I believe humans are better than AI at critical thinking, but it’s a muscle we need to exercise. I don’t think we should outsource our thinking to machines.

Stephanie: I use it minimally, like in Grammarly. But even then, I often don’t trust it and will think, ‘Wait, no, you did that wrong. I like it better this way.’ And sometimes I don’t want my work to be perfect. I want my humanity to show.

Brian: I know my energy is limited, so I direct AI to do the more tedious things, such as arranging a list or creating a schedule. I do the more important work myself.

Maryam: I use it for very specific questions, like you would a tutor. It’s not the first source I would go to. I would search for a tutorial online. I never use it for subjects I like, such as writing and accounting. I want to learn accounting; I don’t want to have ChatGPT do it for me.

Riddhi: As one of my professors said: as long as it’s not doing the learning for you, you should use it – for productivity, for example, and to make up exam questions. Use it for the things you already know how to do but AI can do faster.

Peter: Some of my engineering friends use AI to find areas of research worth exploring. In materials science, they use AI to determine the probability that certain materials are potentially useful and should be tested.

Given how students are already using AI, what – if anything – should universities do differently?

Stephanie: AI cannot be an off-limits conversation. People have to feel comfortable naming when and how they use it. It’s great when folks don’t use it. But let’s talk about how it can be used, the different ways it can be taught and have conversations and workshops about it – as U of T is already doing. It’s important that students learn the difference between being completely stuck and unable to move forward and simply needing to spend more time on a challenging question. We need to teach people that AI is a tool, not to overuse the tool, and to use it in a way that supports them getting their work done. At the end of the day, you’re here to learn and produce work that is yours.

Gabriella: In a lot of my classes, it’s very black and white with AI. Either don’t use it at all, or you’re allowed to use it on certain things that are personal, but never on assignments. I think that’s unrealistic. As much as we’d like to assume nobody’s going to use AI to write an essay because they make bad essays, people will do it. I don’t know how universities should respond to that.

Cameron: I think universities should allow some departments to use AI and some, such as the humanities, to forbid it.

Emmanuel: Universities should stop spending resources and time policing AI. People are going to use it anyway. We should be focusing on teaching people – and evaluating them – for skills that transcend AI: critical thinking, cultivating partnerships, community engagement.

Maryam: I’ve noticed people in writing-heavy classes getting flagged for using AI – even if they didn’t use it. What’s interesting is that a lot of students are using AI to learn how to write. They are mimicking how AI speaks, how it makes a point – even if unconsciously. So, how will professors tell the difference between writing by an AI and a student who has learned to write using AI? It may not be a big problem now, but I think it’ll grow.

Cameron: I see this in my own students. They will use AI as a crutch, where they feel they can’t do something. It’s not like they think AI has a better idea. Most of the time they’re stressed, they need to get an essay done, and they don’t really care about it that much, so they use AI. One thing professors could do, though, is repeatedly tell students they’re smart enough to do the work themselves: “You can do it on your own, you don’t need to turn to AI.”

As AI reshapes how knowledge is produced and shared, what should universities prioritize?

Gabriella: So much about a university is being able to express your opinions – to put out radical ideas, or talk about them, and research subjects outside of the realm of “normalcy.” This is one of the most important aspects.

Peter: University students in Canada are much more likely to call themselves liberal than conservative. What I think this shows is that universities are actually kind of biased. They are promoting some ideologies – leaning toward certain perspectives – and forcing them on students, I certainly feel that in psychology.

Cameron: But everything is informed by ideology, and it is not a negative thing. It’s society’s system of norms. In university, we attack these or deconstruct them – not because we hate society but to ask, ‘Why do we believe this? Why does our society tend toward these things?’ If universities remain a space for free speech, for higher education, for the development of our intellect, we’ll be able to continue to do this.

Stephanie: It’s important to keep in mind that some voices are not always respected outside of these walls. They may be more vocal here because there’s safety within these spaces. I don’t think it’s always about left or right. An elder told me once: “left wing, right wing, same bird.” Even if it sounds like perspectives are leaning one way or another, we still have to fly in a particular direction. If we find ourselves using only one side or the other, we’re going to fly in circles. What’s going to strengthen the university is bringing in more perspectives – more students, faculty, staff, people with different knowledges.

This conversation took place Jan. 8, 2026, at U of T’s FitzGerald Building on the St. George campus. It has been condensed and edited for clarity and flow. The participants were:

- Gabriella Baichwal. Second-year, political science, public policy and urban studies, St. George

- Brian Balev. Second-year, math and economics major, philosophy minor, St. George

- Stephanie Chartrand. PhD, adult education and community development, OISE, St. George

- Jiayi Du. Third-year, information, St. George

- Sunjae Hwang. Second-year, international development studies and economics, UTSC

- Maryam Rehman. Second-year, accounting (management), UTSC

- Riddhi Shukla. Third year, computer science and business, UTM

- Cameron Sparling. PhD, English, St. George

- Emmanuel Taiwo. PhD, environmental science, UTSC

- Peter Yang. Fourth-year, economics and psychology, St. George

No Responses to “ Learning to Think –

or Learning to Prompt? ”

Reading this felt like breathing. Wonderful insights flowing from thoughtful questions - the future is bright! Keep being curious, keep being you.

The last comment sums it up well: you need two wings to fly straight, two perspectives to be fair. Even with an artificial leg, you may be able to walk. And yet, however proficient it may be, you need to remember it's artificial. AI is only as good as the programmer, and it can be biased -- like anything else.

My problem with AI is that it may take away many people's livelihoods. And there are many things that humans can do better than machines, across many human activities.

I've heard some teachers say "thinking is just thinking" and even "thinking can't be taught." But thinking can indeed be taught. I retired from teaching high school math and tech design in 2019. In my approach to cognitive development, I use history as a resource -- as outlined here. (Most of these two dozen web pages were written over 20 years ago and have not been refined since.)