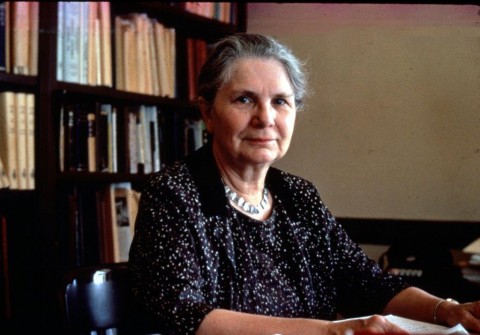

“Beautiful” is an adjective that the renowned astronomer Helen Sawyer Hogg used often in her writings on the cosmos, even in the most scientific of the 200 some-odd papers she published in her 88 years.

Over the course of nearly six fruitful decades until her death in 1993, Hogg was associated with the University of Toronto in various capacities, moving from professor’s wife to unpaid researcher at the Dunlap Observatory, to professor.

Hogg spent many of her nights scanning the heavens, using high-powered telescopes to take about 2,000 photographic plates of variable stars in globular clusters – her particular area. These flashing stars are useful scientifically because astronomers have developed a way to use the period of the flash and their brightness to establish their distance from the sun. By day, she analyzed the meaning of these images, drafted scientific papers, taught classes and helped lead Canadian and international scientific organizations – often enough, she was the first woman to do so, a rare female on whatever podium she spoke from.

She was rare in the circles she moved in for another reason: she not only gloried in the hard science, math and evidence-based theorizing needed to win accolades in her field, but she was a great popularizer, adept at infecting science illiterates with her enthusiasm for explaining the heavens. In her entry-level astronomy class at U of T, she often managed to excite the literature and sociology students who, ho-hum, took it merely to fulfil a science requirement. (For this reason, she’d have been delighted at the recent flash mob–style gatherings at U of T around astronomical happenings: more than 5,000 gathered in Varsity Stadium in 2013 to watch the transit of Venus, and about half as many assembled on the front campus earlier this fall to watch the recent lunar eclipse – clouds, alas, obscured the latter.)

“Helen was as happy introducing arts students to the wonders of the universe as she was discussing complexities in small graduate seminars with rising scientists,” says U of T astronomy professor emeritus Christine Clement, a former student who credits Hogg with helping turn her on to the field.

Hogg also reached out to decent-sized audiences beyond the academy, by contributing a longtime astronomy column for the Toronto Star, writing a 1976 bestseller The Stars Belong to Everyone and explaining the intricacies of the cosmos on TV and in science documentaries.

All of this flowed from her susceptibility to a certain kind of beauty. Ninety years ago, this past January, Hogg was a third-year chemistry major at all-female Mount Holyoke, in South Hadley, Massachusetts. A professor sent her and a trainload of her fellow undergrads to a Connecticut golf course to observe a solar eclipse. “The incredible beauty and grandeur of a total eclipse,” she later wrote, “tied me to astronomy for life.”

There were generations of educated women in her Unitarian New England clan, and so Hogg’s family didn’t balk when she proposed to go to Radcliffe (on a scholarship) to do graduate work in astronomy under one of the field’s great figures, Harlow Shapley. Shapley ran his growing department with bonhomie from a round desk that rotated, and had twelve quadrants, each with different projects on it. He assigned tasks, day and night, by means of slips put in cubbyholes atop the whirling desk. Hogg was lucky in her choice of mentors: he suggested that she study the subject of variable stars and watched over her through the beginning and middle of her career. “He was the man who probably responsible, more than any other, for the shape my life has taken,” she later wrote.

Another of Shapley’s contributions was to introduce her to Frank Hogg, a fellow doctoral candidate and a doctor’s son from Preston, Ontario. After completing their PhDs (him first from Harvard in 1929, her from Radcliffe a year later) and marrying, the pair moved to Victoria so he could work at the Dominion Astrophysical Observatory, which had the second-largest telescope in the world. “I was born then, in 1932,” her daughter Sally MacDonald says, “and the story goes they would bring me to the observatory in a basket. It was the Great Depression, and there was a ban on public institutions hiring both husband and wife, so my mother didn’t get paid at first.”

It was the same at the University of Toronto, when, in the late 1930s, Frank was hired to teach and do research at the new Dunlap observatory, and she continued her research, for a time, without pay. “It was only when the Second World War took male professors into the service, that Helen was given a professor’s job,” Clement says.

At the time of her husband’s death, on New Year’s Day, 1951, she was 45 and the pair had three children (including future astronomer David Hogg). She had to work to figure out how to bear heavy professional and personal loads. “Somehow, she made it happen, but at a cost,” says Maria Cahill, an American academic who wrote her dissertation on Hogg’s career. “Few know that she almost lost heart and quit the profession, but Shapley wrote to encourage her not to. It seems to have made a big difference.”

Hogg, in turn, took her own role as mentor seriously, helping, according to Clement, many young astronomers, especially women, to find a place in the profession.

On the scientific side, Hogg worked in tandem with others to build knowledge of variable stars – the twinklers that she called “performing stars,” because they flash in the way that their more stolid, reliable companions don’t. To ensure the international teams working on the so-called variables were building on each other’s knowledge, she published three catalogues collating information on these – in 1939, 1955 and 1973. “This was important in the pre-Internet era,” Clement says, “and was a project I took over at her death.”

Through this work, she was one of the scientists who helped establish Shapley’s intuition that we are outliers, on the edge of the Milky Way, not at its centre. “I don’t think I’ve made that many earth-shaking discoveries,” she said, with characteristic deprecation. “It’s been more a case of working along and accumulating a lot of information in one area.”

While her job required that she gather and make sense of complex data, Hogg seems never to have lost her appreciation of the beauty that drew her to the field. Just before her 1993 demise, she participated in the making of a popular astronomy video. In it, she comments: “Not to know what’s beyond is like spending your life in the cellar, being completely oblivious of all the wonderful things around us.”

No Responses to “ She Walks in Beauty ”

A wonderful article: very accurate depiction of who Helen was. I worked for her at the Observatory in the summer of 1960. She was a mentor who kept in touch, even as students moved on. I delayed going to graduate school a few years, and she wrote to encourage me, and she also continued to write letters of recommendation on my behalf. Helen was a wonderful role model.

Is it just a coincidence that this lovely article, 24 years after the death of Helen Hogg, has appeared about the same time as a Heritage Toronto Legacy plaque?

The plaque, near 2875 Yonge Street, provides the bare-bones information: "The astronomer Helen Sawyer Hogg (1905-1993) lived here from 1962 to 1965." Apparently she shared an apartment in the building at that address with Mary Quayle Innis, widow of the famed historian, Harold Innis. The commuting distance to the downtown, campus was, of course, much less than from her Richmand Hill home.