Investigating Crime, One Fake Body at a Time

U of T Mississauga’s forensic science program gives students a unique training experience Read More

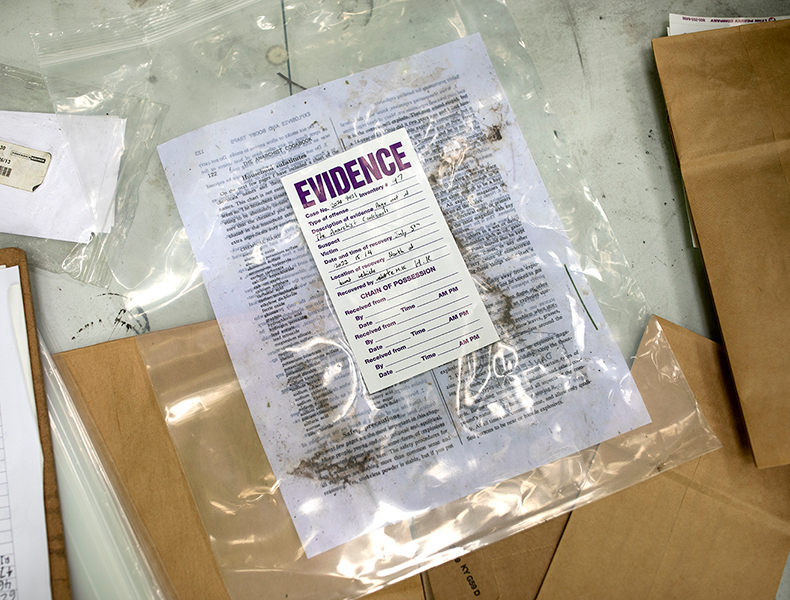

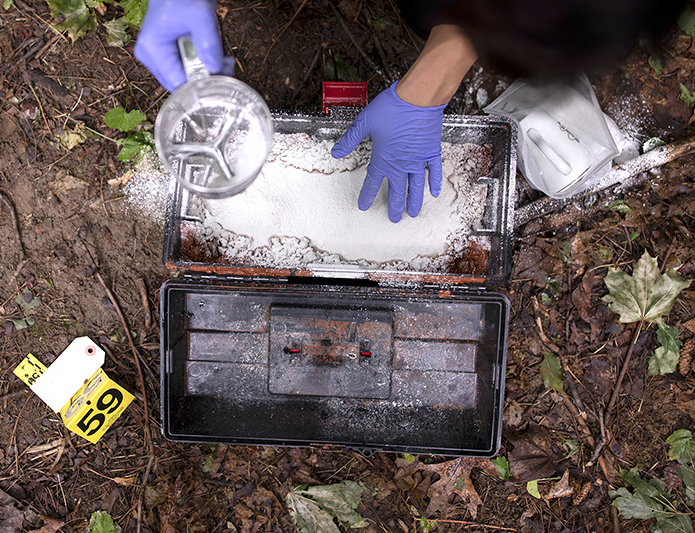

An emergency responder briefs the investigators who have gathered at U of T Mississauga: a body, along with shrapnel and pages from The Anarchist Cookbook, has been found outside a house adjacent to a shipping container. Another body lies near a car. On the vehicle’s roof appears to be the remnants of an explosion. If not for the mannequins, the area might be mistaken for a real crime scene. That is the point.

The staged setting is part of the degree program in forensic science at U of T Mississauga, and is designed to give upper-year students “on-the-job” experience as a crime scene investigator before they graduate. The work involves everything from securing the location and collecting evidence such as fingerprints and DNA, collaborating with forensic chemistry students to analyze what they’ve found, and later testifying in a mock courtroom.

Sahana Pirapakaran, a fourth-year student specializing in forensic anthropology, worked on the simulated crime scene earlier this year and found the set-up highly realistic. “I felt like I really was a crime scene officer,” she says.

Graduates of U of T Mississauga’s forensic science program have gone on to work at Toronto Police Services and other law enforcement agencies, the RCMP and the Centre for Forensic Sciences.

The detailed scenes, which are prepared by the program’s staff, are also used to give high school students, rotary clubs and other community groups a firsthand introduction to crime scene investigations. Murray Clayton, the program officer and outreach co-ordinator, likens these one-day events to an “educational escape room” in which participants get a chance to solve the “crime.”

Although students in recent years have been drawn to forensics through the television show CSI, it doesn’t take long for them to realize that what they see on TV is far from reality. On screen, one forensic investigator typically collects the evidence, analyzes it in the lab and solves the case. In real life, each task goes to a uniquely trained forensic specialist, such as an anthropologist, biologist, chemist or psychologist.

Pirapakaran says her experience with the mock investigation hammered home how little room for error there is. “In a real-life situation, you don’t get a redo,” she says. “You’re dealing with someone’s life.”

At U of T Mississauga, forensics students wear jackets with patches on the sleeve (like Scout badges) representing their area of focus – a skull, for instance, represents forensic anthropology. Only a few people can claim a patch for each specialty offered at the campus; one is Prof. Tracy Rogers, the program’s director since 2001.

For Rogers who has worked on some of the highest-profile cases in Canada, the work of forensic investigators helps society answer questions about criminal activity and puts to rest questions that family members have about their loved ones. “In a sense it helps the victim,” she says. “At least having their story told and getting some kind of justice for them is a valuable service.”