On December 13, 1937, the Japanese imperial army captured the Chinese city of Nanking (now Nanjing). Within six weeks, the soldiers slaughtered an estimated 300,000 Chinese civilians and raped as many as 80,000 girls and women. These horrific atrocities became known as the Rape of Nanking.

I was born in Canada to Chinese parents. From elementary school through university I learned about the Second World War, but only about events in Europe. It was at home that my parents told me about the war in Asia. My mother remembered sitting on her father’s shoulders as people rallied in Hong Kong to raise money to defend against the Japanese army. My father said he had been chased and kicked by Japanese soldiers in Shanghai every time he and his mother left the protected French Quarter to buy rice. They spoke about the cruelty of the invading soldiers but never of the Rape of Nanking. Only in 1998, after stumbling upon Nancy Tong’s documentary In the Name of the Emperor, and meeting Iris Chang, who wrote The Rape of Nanking, did I learn about the depths of what had happened to my ancestors during the Second World War. I was shocked and angry that so little had been said about this “forgotten Holocaust” and that there had been no compensation for the victims of Nanjing from the Japanese government, which long denied responsibility.

I decided to write a play as a way of giving a voice to those who could not – or would not – speak for themselves. However, my Chinese and Japanese acquaintances were not prepared to share their stories; there seemed to be a collective amnesia when it came to the topic of Nanjing. My parents cautioned me that the Chinese community would not come to see a play like mine because those who had suffered through the war did not want to relive it. Yet I persisted – in the belief that there can’t be healing or reconciliation without discussion. Slowly, my family began to open up. During the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong, students at my mother’s school had been segregated. One day, my mother said, she crossed the white chalk line in the playground that divided the Chinese and Japanese students in order to help a Japanese girl who had fallen and hurt her knee. I included this scene in my play to shine a light on how compassion can conquer the hatred bred by war.

In January 2008, I visited Nanjing for the first time and met Chang Zhiqiang, a Nanjing survivor. Mr. Chang, then almost 80, was 10 years old when he witnessed a soldier stab his mother with a bayonet. Before she died, she motioned to Chang to find his baby brother, whom she could hear crying. Chang found the infant crawling on a patch of snow stained with blood and brought him back to his mother. This haunting image became the title for my play, Red Snow. Later, Mr. Chang took me to Swallow Cliff, one of the sites of the massacre. This was where the citizens of Nanjing were taken and told they would be set free. Instead the soldiers forced thousands to plunge to their deaths in the Yangtze River. I looked down into the water, remembering the photos I’d seen of bodies washed up on the banks below. I thanked and hugged Mr. Chang and got on the bus. As I headed back to my hotel, I broke down in tears and resolved to finish my play.

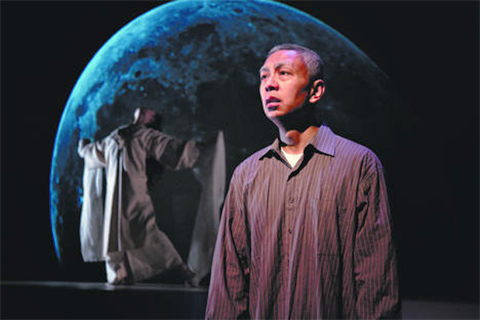

Red Snow premiered in Toronto last January and in Shanghai in November, and I hope to take it to other parts of the world as well. The play has been submitted to theatre festivals in Turkey, a country where those aware of the challenges of facing up to the Armenian genocide may find a meaningful affinity in Red Snow’s message of truth and reconciliation. I hope my story will open dialogue between communities, inspire others to break the silence, give back voices to those who were silenced and contribute to our much-needed collective healing.

Diana Tso (BA 1990 NEW) is the playwright and producer of Red Snow.

No Responses to “ Nightmare in Nanking ”

It is time more from the Chinese community took up the task of publicising of the Chinese Holocaust. Of course, Nanking was one example only. In the Co-Properity Sphere, the Japanese murdered 23 million ethnic Chinese (See emeritus Professor Chalmers Johnson) .

I had the great pleasure to see a production of Red Snow about a year ago. The acting and production values were exceptional. I loved how Diana brought a dream-like quality to it yet allowed for reality to crash in as the story unfolds. It was an excellent evocation of this horrible period in history that I knew very little about. I came away with a deeper sense of the tragedy of war, how it shapes our futures and how we must heal in order to move forward. There was a standing ovation when the play ended.

I highly recommend that readings of the play be given at every university and college in Canada and I hope that it also becomes a commercial success so that the playwright can continue to work her talent.

Barbara Chernin