Drawing Connections

Professor Ai Taniguchi explores how art and language can bring us together

Ai Taniguchi was six when her family moved to the United States from Japan, and she’ll never forget how scary and lonely it felt to start Grade 1 barely knowing a word of English. She learned quickly, but it was her love of art that first helped her bridge the language barrier.

“I’d sit with my notebook on a bench drawing at recess, and the kids would come over and ask me to draw them or their favourite cartoon characters,” she says. “It was like they saw a part of me even though we didn’t speak the same language, and I felt a lot of joy.”

Today, Taniguchi is an assistant professor of linguistics at University of Toronto Mississauga, where she uses art – specifically Japanese-style comics called manga, which she grew up reading – in her teaching and public outreach aimed at increasing awareness of the crucial role language plays in people’s everyday lives.

“Comics are inherently relatable because they’re easy to read, understand and share,” she says, noting that an image plus a few words can convey complex linguistics concepts. When she’s teaching about sentence ambiguity, for example, she shows a comic illustrating the two potential meanings of “Darth Vader will poke the dog with a lightsaber.” (See below.)

She even coined a term, “graphic linguistics,” to describe the intersection between her two passions. “Art has always been my safe space,” says Taniguchi, who has never had formal art training. “It allows me to capture the chaos of all the ideas going around in my head.”

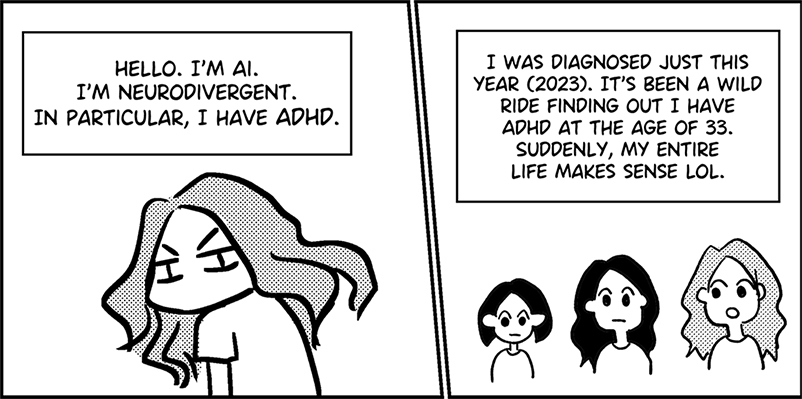

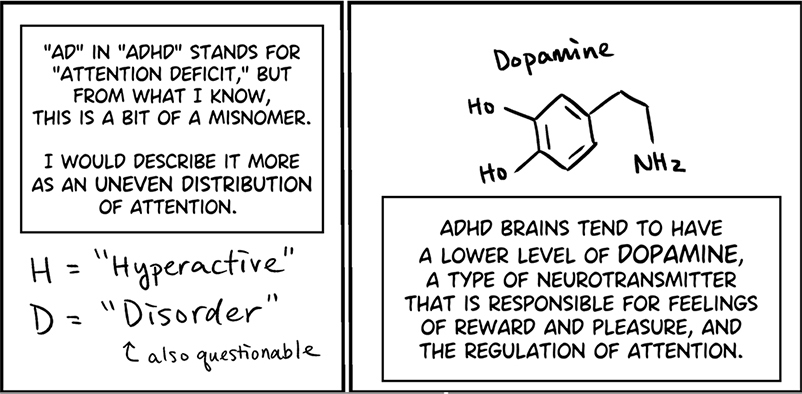

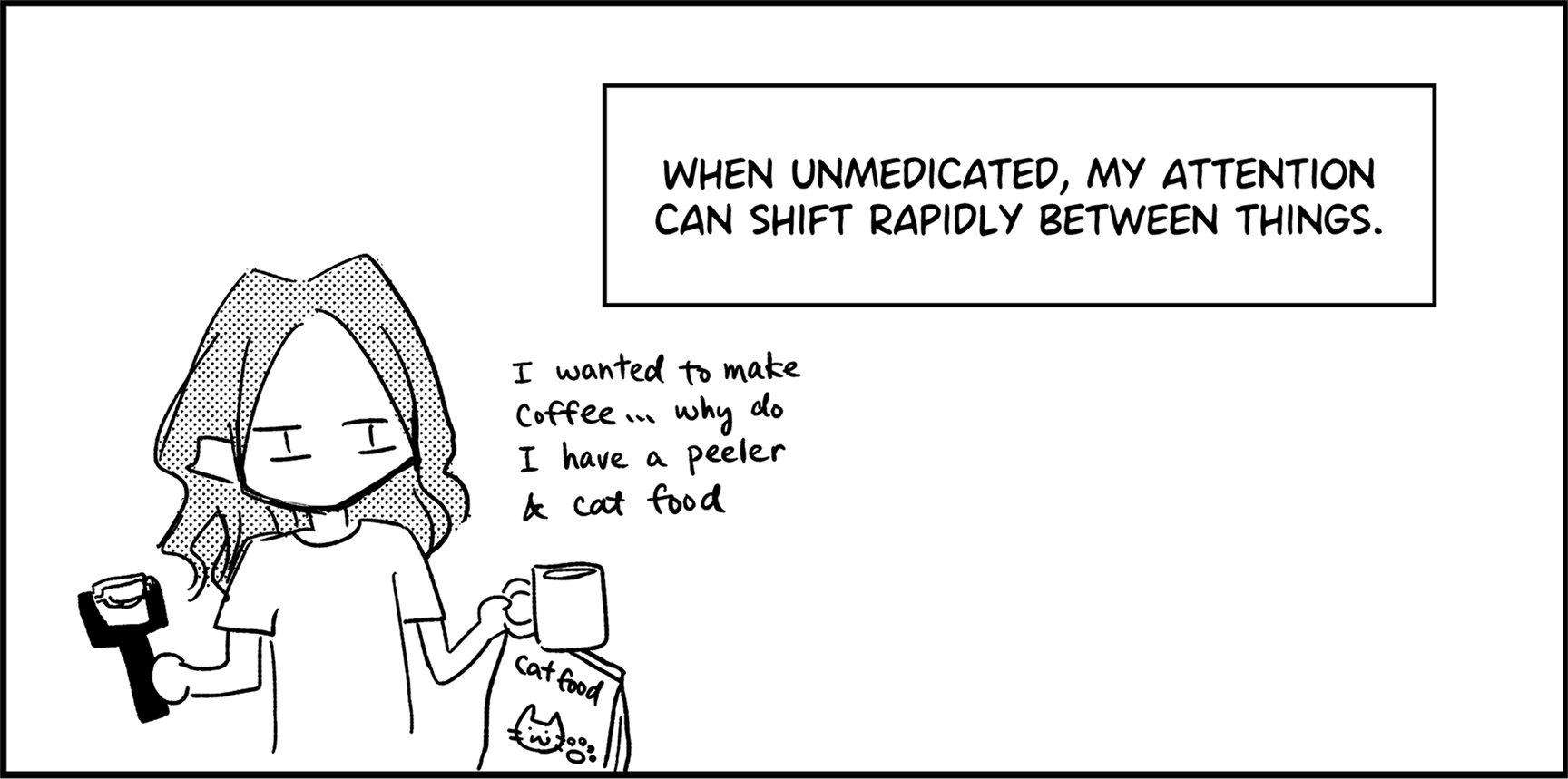

Last year, at 33, she was diagnosed with ADHD – something that has helped her make sense of what she calls the “hyperactivity in my mind.” While she acknowledges that it’s difficult to tease out the connection between her lifelong visual creativity and how her brain works, Taniguchi knows that she has consistently turned to images to make sense of the world. “Injecting art into everything that I do has just been an instinctive practice for me,” she says.

Yet she’s also naturally inclined toward learning about languages. “Being bilingual in Japanese and English, I was constantly wondering about things like the patterns across languages and why there were words for certain things in Japanese but not in English,” she says. “When I was deciding what to study at university, I ended up Googling ‘Is there a study of languages?’ and discovered linguistics. That’s where it all started.”

The first time Taniguchi formally combined her two interests was when she created a comic related to an undergraduate linguistics class she was taking. “It was a goofy little thing on a piece of paper with two cats talking about sentence structure. I sent a picture of it to my professor, who put it up on her office door,” she says. “Eventually, I posted it online, where it got a lot of attention from linguistics groups on social media.”

At first, Taniguchi was aiming for a research career in linguistics, driven by the thrill she got from discovering new things and believing that she was too introverted to be a good teacher. Then she got her first teaching assignment in grad school.

“I suddenly realized that teaching might be one of my talents, because I know from my cultural and linguistic background what it’s like to literally not understand or be understood by people,” she says. “That’s a very tough thing. It’s a feeling that I don’t want other people to experience, especially when something can be made more accessible.”

Long before she knew she had ADHD, Taniguchi used teaching strategies that would have helped her when she was a student, such as simplified explanations, repetition and drawings – often humorous ones.

“I immediately found a lot of satisfaction and joy in thinking about how to make linguistics fun and relatable to students,” she says. “I know now that if I teach for an ADHD brain like mine, it also benefits neurotypical people.” Her students say that she makes complicated ideas relatable and that she creates a welcoming environment for all types of learners – in part by sharing her ADHD diagnosis. “Her teaching approach is compassionate and engaging to students from all walks of life,” says PhD student Kate Prigaro. “She frequently uses comics to start conversations about the relationship between language and our lived experiences – including neurodivergence, immigration, racism and more.”

Taniguchi recently completed a major project 1 that used her comics – which she now draws digitally using a large tablet and stylus – to illustrate the individual stories of U of T students who speak languages ranging from Arabic and Anishinaabemowin to Punjabi and Urdu. The project idea sprang from students’ reactions to comics she had created and shared in class about her own challenges navigating two languages.

- 1

The project was called Language, Identity, Multiculturalism and Global Empowerment, or L’IMAGE

“The comics are quite personal, and students expressed gratitude that I’d highlighted things they had been through,” she says, adding that she has learned through conversations with experts in the more established field of graphic medicine that comics can make the treatment of heavy topics easier. “I started making comics because I wanted a lighthearted way to explore the painful parts of my history, but I also hoped that many people would relate to it in a place as diverse as U of T.”

When she put out the call for multilingual students to share their stories for the project the response was overwhelming. In the end, she secured enough funding 2 to interview and create comics for 13 students. Their stories focused on misconceptions about their languages, racism, the ups and downs of multilingual families and more. Infographics with facts about the featured languages accompanied each comic. Taniguchi shared the comics widely through social media and an exhibit at U of T Mississauga.

- 2

Financial support was provided by the U of T International Student Experience Fund

“The participants said that they felt seen and not alone because they got to tell their story and witness people relating to it through online and in-person comments,” she says. “At the exhibit, it was heartwarming to see so many people read the comics and say, ‘That exact thing happened to me.’”

Beyond the classroom, Taniguchi makes time to educate the wider community about linguistics through her website, public lectures, high school talks and social media. No matter the platform, she incorporates drawings and comics. “My drive to reach a big audience comes from my experience,” she says. “I struggled with my sense of identity as a Japanese-English bilingual person growing up in a very white neighbourhood in Peachtree City, Georgia. I was one of few visible minorities, and I was made to feel like being Japanese and speaking Japanese wasn’t cool.”

When Taniguchi arrived at U of T Mississauga in 2020 and realized how richly diverse the student body was, she says she felt safe and seen. “The normalization and appreciation of diversity here is very different from the communities I grew up in. What linguistics can do is get people curious about different languages, rather than saying, ‘I don’t like it because it’s different.’”

The path has been bumpy, but Taniguchi now celebrates her differences, whether it’s the language she speaks, the way her brain operates, or her comics-based academic methods. “We’ve had standard expectations for teaching and communicating research for a long time, but they don’t work for all students or professors,” she says. “I’m glad to challenge those norms.”

“The great thing about comics is that they tell stories that hook people. They can help students understand a complicated linguistics concept or allow them to share their experiences managing multiple languages and identities. Personally, comics have allowed me to say, ‘Hey, is there anyone out there who’s like me?’ When people respond, I have a sense of visibility and community, and it feels like my identity is valid.”

Finding the Right Word

Sometimes a term in one language has no direct equivalent in another. Taniguchi gave us three of her favourite examples from Japanese and English.

さすが (sasuga)

This means, “I’m impressed by something you’ve done but, knowing you, I shouldn’t be.” For example, you, Sal and Teresa go hiking, but you and Sal forget to bring sunscreen. Teresa, the responsible one, reveals that she brought sunscreen for everyone. You might say “sasuga Teresa.”

お疲れ様 (otsukaresama)

This greeting acknowledges someone’s hard work with a general sense of gratitude and care for their well-being. You might say to a colleague leaving the office to go home, “otsukaresama!”

切ない (setsunai)

A mix of sentimental, sweet, painful, heartbreaking and pure. You find out that your crush is dating someone new by seeing the two of them out on a date. This is setsunai.

Ai Taniguchi’s Comics

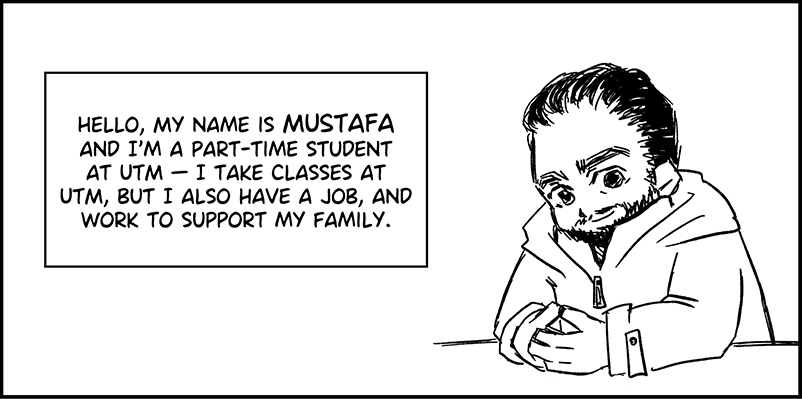

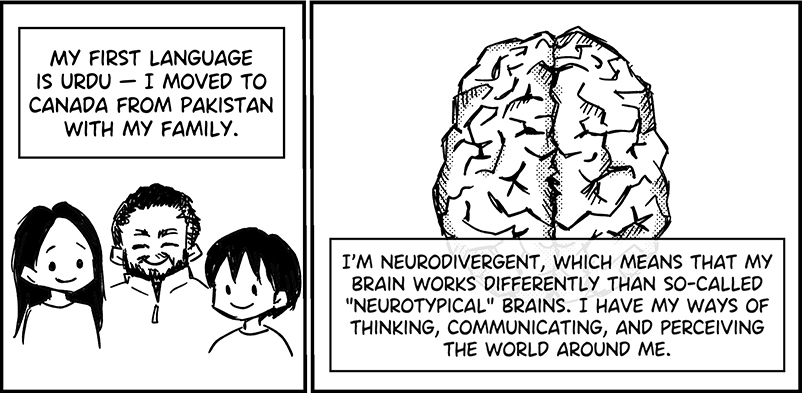

In 2023, Ai Taniguchi spoke to 13 multilingual students about their experience with languages in their everyday lives, and then turned their stories into comics. She says her goal with the comics was to contribute to cultural awareness and advance the idea that all forms of language are valid.

The project, called L’IMAGE (which stands for “language, identity, multiculturalism and global empowerment”), was a collaboration with the International Education Centre and the department of language studies at U of T Mississauga.

Below, Taniguchi tells the story of Mustafa, who, like her, is neurodivergent. “Mustafa’s story was highly relatable and timely for me because I had recently been made aware of my ADHD,” she says.

“I’m very proud of the art in this piece,” says Taniguchi. “This is the first comic I made after a workshop with experts in the use of comics for communicating medical science, from the U of T’s Biomedical Communications program. The improvement in my visual story telling is noticeable compared to my previous comics.” Read the full comic.

During the L’IMAGE project, Taniguchi kept a record of her own experience, sharing her behind-the-scenes thoughts as the work unfolded. Below is a comic she created about that.

“This particular journal is a personal one,” says Taniguchi. “I was diagnosed with ADHD that year, and it made me realize why I love working on creative projects like this.” Read the full comic.