Rosita Bilas arrived in Canada from the Philippines in 1990, and a few years later took up residence in a three-storey public housing apartment in Toronto’s Regent Park, east of the city’s downtown. She’s worked as a caregiver while raising two sons. Recently, however, Toronto Community Housing Corporation (TCHC) officials told Bilas that her apartment building, a deteriorating walk-up, would soon be demolished as part of a sweeping redevelopment of the 28-hectare public housing complex. The agency said it would offer her a replacement unit until a new one is completed.

Bilas had a couple of options, the officials added. She could apply to live in one of the new TCHC apartments, where rents are tied to the occupants’ income. Or, if Bilas could muster the down payment, she could buy one of the condos that would be built within Regent Park as part of the agency’s strategy to increase density and bring a broader mix of residents into the area. At the time, Bilas’s income had been rising, so she was paying the maximum rent – about $1,100 per month. “I said to myself, I’m paying more rent so why not move to the new condo?”

For Bilas, who has never owned a home, it will be a big move in every way. If a tenant’s income drops due to illness or job loss, TCHC will reduce the rent accordingly. But mortgage lenders are not so forgiving. “Because I’m a first-time buyer, I’m nervous,” she says. “I pray I always have a job and good health. It’s a big responsibility.”

As it happened, the Daniels Corporation, the developer founded by John Daniels (BArch 1950) that was chosen to lead the $1-billion redevelopment, had helped create a financing program for Regent Park tenants who almost have the savings and income to make the move from renting to owning – but aren’t quite there yet. Through the “Foundation Program,” buyers can borrow up to 35 per cent of the purchase price of their condo or townhome, but the loan is structured so that the owner only has to pay it off with the proceeds of the eventual sale of the unit. Bilas applied, and qualified for, a loan towards a unit in a condo due to be finished next year. “That was a big help for me,” she says.

Now, Bilas is looking forward to living in a clean building with new appliances. And after 15 years of hauling groceries up three flights of stairs, she particularly relishes the prospect of being able to use an elevator to get to her unit. As a single woman who sometimes works nights, the security in the condo will provide additional protection in a neighbourhood with more than its fair share of crime. Indeed, she is hopeful that the influx of new condo owners will improve the Park’s overall safety.

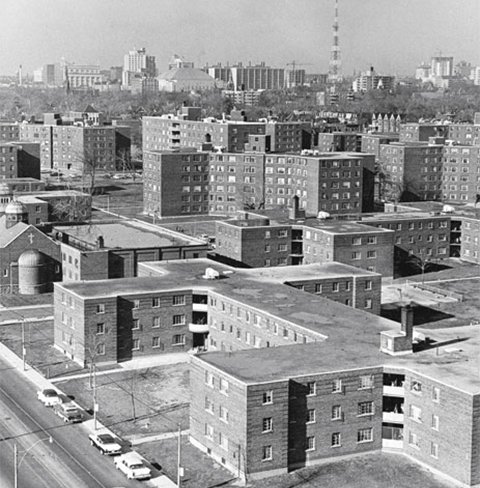

Like thousands of other Regent Park tenants, Bilas is living through a closely watched transformation of Canada’s oldest housing project, a place that had become synonymous with derelict apartments, gang rivalries, drug crime and, for a time, aggressive policing. Though situated just blocks from the upscale streets of historic Cabbagetown, Regent Park often seemed like a world apart, its 7,500 residents consigned to navigate a parallel universe characterized by a dearth of amenities and economic hope, as well as deeply disturbing – and all too common – incidents of violence.

But like all stereotypes, the negative reputation that has tailed this neighbourhood doesn’t tell the whole story. By the early 2000s, almost 60 languages were spoken in the Park, which had become a hive of artistic, cultural and educational activities. The physical transformation that’s been underway for several years is now reconnecting Regent Park with the adjacent neighbourhoods and bringing in a mix of market and subsidized housing. “It’s been a very challenging road to get here,” remarks Mitchell Cohen, a former co-op housing developer and musician who has worked for the Daniels Corporation since 1984, and is a volunteer with U of T’s John H. Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design. “On the ground, things are feeling really fantastic. We’re at a great moment where we can see the results.”

***

The story of Regent Park closely tracks aspects of the city’s evolution during much of the past 80 years. But it is also a tale in which members of the University of Toronto community have played a long and involved role that begins at the very outset of the political movement to improve the city’s Depression-era housing conditions. Early in 1934, Toronto city council established a commission to investigate the development of so-called “slums,” including Moss Park, a dense working-class enclave northeast of Queen and Sherbourne. The idea for the inquiry came from Herbert Alexander Bruce, a former professor of surgery at U of T and founder of the Wellesley Hospital who, by that point in his career, was also serving as the province’s lieutenant-governor.

An outspoken figure, Bruce warned that Toronto’s slum districts needed to be blotted out in favour of a program of “planned decentralization.” Surveys and interviews conducted by the Bruce commission found hundreds of neglected, overcrowded houses in need of repairs, many without baths or central heating. Backyards were filled with junk, while the rear laneways didn’t conform to fire regulations. Some factories in the area operated around the clock, forcing residents to “tolerate the noise of the machines and trucks day and night.” The commission’s conclusion: Moss Park was “unsuitable as a residential district.”

While social reformers such as Leonard Marsh, father of Canada’s social safety net, began pushing for a federal housing authority in the mid-1930s, there was no meaningful progress until the post-Second World War years, when the City of Toronto bulldozed south Cabbagetown and built what came to be known as Regent Park North.

“The designers did what was good design for the time,” says urban housing and poverty expert David Hulchanski, the Dr. Chow Yei Ching Chair in Housing at U of T’s Factor- Inwentash Faculty of Social Work. Following modernist planning principles sweeping across the West, the new apartments, geared at low-income working families, were situated in a park-like setting, with plenty of open space, ventilation and sunlight.

A decade after Regent Park was built, affordable housing advocate Albert Rose, also a professor (and later dean) in U of T’s Faculty of Social Work, completed a detailed review of the project. Rose – a towering figure who served as the vice-chair of the Metro Toronto Housing Authority – said the Regent Park experience clearly indicated that such largescale, publicly funded housing projects only came about as a result of concerted pressure from local citizen groups. On the eve of the 1960s, he declared the experiment a success: “The name [Regent Park] has become a symbol of successful public action and public housing experience.”

Rose’s optimism, while justifiable at the time, eventually missed the mark. What initially appeared to be a successful approach to social housing gradually morphed into a poverty trap for generations of low-income Torontonians.

Soft-spoken and casual in comportment, Cohen, president of the Daniels Corporation, certainly does not cut the figure of a major developer in a city where developers have played a significant role in recent years. Sitting in a cluttered conference room in Daniels’ sleek showroom on Dundas Street, in the middle of Regent Park, Cohen comes across as the anti-developer, often sounding as much like a social advocate as a businessman.

He comes by that pedigree honestly. Raised in Regina, he graduated from McGill University and the London School of Economics and Political Science before taking up a job with the Co-operative Housing Federation of Toronto in the late 1970s, facilitating the development of non-profit co-ops.

After Brian Mulroney’s conservative government cancelled the federal government’s co-op housing development program in 1984, Cohen went to work for John Daniels at the Daniels Corporation. The two continued to develop social housing projects until Mike Harris’s Tory government in Ontario killed the province’s program. At the time, two-thirds of the Daniels Corporation’s revenues came from affordable housing projects, and so the company had to refocus its strategy. But Cohen and Daniels didn’t turn their backs on the nearly moribund non-profit housing sector; as Cohen well knew, there was still plenty of need.

In the three decades since Albert Rose declared Regent Park a success, much had changed in the social housing world. Monolithic public housing complexes in many North American cities had fallen into the grip of crime and entrenched poverty. In Regent Park, Hulchanski says, the demographics shifted radically. The first wave of residents – the white working poor – was succeeded by visible minority residents, and a growing concentration of welfare recipients. The initially lauded design – apartments in a park setting – proved to be highly problematic. Because the city had erased the old block network during the construction, Regent Park lacked so-called “eyes on the street”; with its many blind spots, the Park became a haven for gangs.

During the 1970s and 1980s, reform-minded mayors such as David Crombie and John Sewell promoted an entirely different approach to affordable housing. They championed higher-density, mixed-income communities such as St. Lawrence, with its co-ops and in-fill housing projects designed to blend in with their urban surroundings.

Meanwhile, the problems at Regent Park and other older social housing complexes began to pile up. Due to waves of economic uncertainty from the 1970s to the 1990s, urban poverty rates began to grow as well-paying manufacturing jobs disappeared. Tens of thousands of people, many of them recent immigrants, languished on waiting lists for subsidized apartments. But as the tenant population in social housing complexes became poorer, crime and drug-dealing escalated. And to make matters even more complicated, the agency faced a crushing backlog of deferred maintenance on its aging apartments, including Regent Park; the current cost is estimated to be at least $750 million.

In the mid-2000s, when TCHC and the City of Toronto embarked on the plan to redevelop Regent Park instead of fix it up, the math looked promising: the area had relatively low densities but the land was valuable due to mounting demand for downtown condo living. The idea was to use the proceeds of the sales of condo units to underwrite rebuilding the subsidized units. Chicago’s housing authority had made similar moves, demolishing notorious public housing complexes in desirable locations and selling the land to private developers. In this case, however, TCHC pledged to replace all of the subsidized apartments within Regent Park by boosting the area’s density. The plan called for increasing the population of the area to 12,500, and aiming for a 60-40 mix of market-rate and subsidized apartments.

Don Schmitt (BArch 1977), a principal of Toronto’s Diamond Schmitt Architects, and planner Ken Greenberg (BArch 1970) both played key roles in drawing up TCHC’s master plan. They pushed for basic urban design principles meant to reconnect Regent Park to the rest of the city: a conventional block-based street grid and a mix of housing forms, including townhouses, mid-rises and a few towers (including one highrise that encases the exhaust stack of a district heating system). Where the old Regent Park had no commercial amenities, Schmitt says the new plan re-established Dundas, which bisects Regent Park, as the area’s commercial spine and social focal point.

“I think a lot of those lessons from 1970s and 1980s–vintage mixed-income communities have been integrated into the Regent Park master plan,” observes Schmitt. He notes that the residents, during extensive community consultations, stressed that they wanted to live in a normal neighbourhood, not an architectural showcase that drew attention to itself. “The most important decision the community made was to reshape the former public housing project into a neighbourhood like any other,” says Greenberg. “That meant above all complete connectivity – let the streets run seamlessly through the site making all possible links and erasing boundaries.”

When the Daniels Corporation won the bid to redevelop Regent Park, Cohen had to transform that elegant redevelopment strategy into a marketable bricks-and-mortar reality, meaning the firm had to build and sell condos in an area long seen as best avoided. In its first phase, the company used a variety of architects to create visual variety, and also brought in commercial amenities such as a supermarket, a bank and a coffee shop – all services conspicuous by their absence in the old Regent Park.

“People in this neighbourhood said, ‘This is missing, this is not normal,’” Cohen says, noting that dozens of Regent Park residents now work in those new businesses. Indeed, once Phase One opened in 2010, “we couldn’t tell where a condo is and where a rent-geared-to-income building is. They’re indistinguishable and they’re on a public street.” (TCHC planners toyed with the notion of creating buildings with both rental and condo units, but decided such an approach would be difficult to market.)

Yet the Daniels Corporation has sought to blur the social lines with two innovative financing programs designed to help moderate-income, first-time homeowners put together a down payment. The company says about a third of the 469 condo units in two of the first market buildings were purchased by such buyers, using a mortgage assistance program. Another 13 owners, Bilas among them, had been Regent Park tenants, and made use of a second financing scheme – the Foundation Program. “With a little assistance, they can buy and move out of social housing,” says Cohen. “This is one of the strongest tools for breaking the cycle of poverty.”

But the Regent Park revitalization isn’t just about residential buildings, shops and a rebuilt street grid. Various public institutions have made parallel investments designed to create a more complete neighbourhood. The City of Toronto last fall opened a new aquatic centre, while the Toronto District School Board mounted an extensive renovation of Nelson Mandela Park Public School. TCHC and Maple Leaf Sports and Entertainment are also collaborating on a large new sports field for the community, to be built in 2015.

The Daniels Corporation, for its part, tweaked the master plan to create other public spaces and amenities. During a thorough public consultation into Regent Park’s social and cultural development, residents had told TCHC and the City about dozens of local groups working in basements and corners of Regent Park. But the master plan made no allowance for an arts and cultural hub. What’s more, the development timetable delayed the construction of a central park until 2020, which meant the first new residents would be waiting for years for a public space. “We said to TCHC, we need to fix this,” Cohen says.

After rejigging the phasing strategy to accelerate construction of the park, which will now open this spring, the company decided to carve out space for a new cultural centre that would provide a venue for all those local organizations. Designed by Diamond Schmitt Architects, the colourful three-storey structure includes several state-of-the-art performance spaces, a locally run café, a green roof, and two floors for various educational, arts and community groups that have long operated in and around Regent Park. Many relied on informal or rented space, and some had been uprooted when the demolition began. The need for this kind of social infrastructure remained. “The inspiration came from the neighbourhood,” says Cohen. “It came from the ground.”

One of Regent Park’s most enduring self-help organizations is the Toronto Centre for Community Learning & Development, which was founded in 1979 as East End Literacy and administers a friendly storefront space known as the Daniels Centre of Learning, located kitty-corner to the Spectrum. In the mid-1990s, the group decided to move beyond one-on-one literacy training and began to offer a broader range of services, including job-readiness training and immigrant women’s integration programs, says its longtime executive director Alfred Jean-Baptiste. Last year, almost 9,000 people participated in the centre’s programs, including an innovative course designed to train local teens to teach their parents to speak English.

The learning centre has also cultivated active partnerships with several post-secondary institutions, including U of T. The link dates back about a decade, when Sheldon Levy, then a U of T vice-president (and now president of Ryerson University), approached Frank Cunningham, a professor of philosophy and political science at Innis College, about improving the university’s community outreach. After asking around, Cunningham found out that New York University and the University of British Columbia offered non-credit lecture courses in some of those cities’ low-income neighbourhoods, with UBC’s operating from a space in the Downtown East Side.

The partnership between the community learning centre and U of T went ahead in 2003 and in the years since, it’s thrived. Professors from a variety of disciplines have volunteered to deliver lectures as part of seminar-style courses ranging from starting a business to the history, economics and culture of fashion.

The participants are predominantly immigrant women, many with degrees; the lecturers often come away from those seminars having learned as much as the students, says Cunningham. “It really is a two-way exchange.” He recalls how, during a lecture about multiculturalism, a woman from Somalia raised her hand and asked, “How come there are so many homosexuals in Canada?” There were none in her home country, she continued. Suddenly, another participant interjected: “What part of Somalia do you live in?” There were many openly gay and lesbian residents in the Somali city where the second participant had lived. That exchange, Cunningham says, precipitated a spirited debate about attitudes towards sexuality, both in Canada and Somalia. “Those are no-holds-barred discussions.”

Today, the U of T partnership is overseen by Shauna Brail, a senior lecturer and director of the Experiential Learning Program at Innis College, which places urban studies students in apprenticeships at the Regent Park learning centre and other organizations across the city. “It’s very much a mutual, two-way learning activity,” she says. “What my students come back saying is, ‘I’ve never met people who lived in Regent Park and didn’t realize the challenges and struggles, and what’s needed to survive in Canada.’”

Another, more recently established program at U of T’s School of Continuing Studies is aimed at Regent Park residents with a university degree who want to improve their work skills. One such resident, Nyla Khan, was a teacher in her native Pakistan before she arrived in Toronto as a landed immigrant in 2005. Despite eight years of experience in her native country, Khan has struggled to restart her career as an educator. Last year, through the Continuing Studies program, she enrolled in two professional English courses to help prepare her for a language proficiency exam that she needs to obtain a teaching certificate in Canada. Ultimately, Khan wants to work as an educator so she can fully support her daughters. One is now at university and intends to be a physician; the other, in Grade 9, aspires to become a police officer. “I pray for them that every day they’ll achieve their goals,” she says.

***

Such messages are hardly lost on Mitchell Cohen, who has had to preside over a wrenching process that involved dismantling the physical infrastructure of a community in order to rebuild and, hopefully, improve it. In fact, Cohen, who has been writing and performing music for decades, found himself moved to compose three songs about the dramatic and, at times, unsettling transformation of Regent Park. The first song, “My Piece of the City,” is a jazzgospel piece about the anxiety, fear and even the sense of loss precipitated by the first tranche of demolition activity. The second and third are more forward-looking and hopeful, and focus on the moments in 2010 and 2012 when the former residents moved back to a community outfitted with streets and gleaming new buildings.

While these sentiments may at first seem forced coming from a successful businessman, they appear to be widely shared by residents such as Rosita Bilas, who says she definitely wants to return to Regent Park and take up residence in one of the new rental buildings. Compared to other parts of the downtown, she says, “I feel the air is fresher in Regent Park.”

Sixty years ago, social reformers such as Albert Rose and hundreds of working class families felt much the same way about the development of the original Regent Park and the demolition of the crowded, impoverished and heavily polluted neighbourhood that it replaced.

So who’s to say the current revitalization won’t also succumb to the law of unintended consequences? “I’ve thought about that a lot,” admits Hulchanski, who has spent the past several years closely charting the historic patterns of poverty in Toronto. He is, nonetheless, optimistic, because the new neighbourhood has turned its back on the “extremism” of modernist, 20th-century planning, which regulated urban texture and diversity right out of such communities, leaving them barren and vulnerable to social dysfunction.

The current redevelopment, by contrast, has sought to physically bring the city back into Regent Park. Like much of Toronto’s downtown, the neighbourhood will feature city streets, compact blocks, businesses, community services and residents from across the socio-economic spectrum. What’s more, the investment in community amenities will attract development in the areas adjacent to the Park. “As time passes,” Hulchanski predicts, “people won’t know where Regent Park begins and ends.”

Click on the image below to start a slideshow with captions.

No Responses to “ The New Regent Park ”

Wow, what a great idea.

Phase 1 looks wonderful. I remember the name Regent Park has always had a bad rap, so was surprised that a new name was not invented. But I understand the pride in it. Regent Park has come full circle and the community is thriving.