Strange Bedfellows

A growing number of city-dwellers live in condos – and now high schools, theatres and daycares are taking up residence there, too

St. Monica’s describes itself as the “mother church” for Catholics living in midtown Toronto. First built in 1959, the cruciform building has since been restored, refurbished – indeed, resurrected – several times in its long life.

But hobbled by maintenance costs and accessibility concerns, St. Monica’s was eager to avoid the same fate as 9,000 other churches currently slated for closure across Canada.

Until it found partnership with the condominium industry, that is. Over the next few years, the mother church is awaiting final approval on a “mommy makeover” that will see it torn down, rebuilt and connected to a 44-storey condo building. St. Monica’s will continue its mission in a sparkling new $17-million church offering a full range spiritual and social programming.

“The idea started with the parishioners,” says James Milway (BA 1973 St. Michael’s), chancellor of temporal affairs for the Archdiocese of Toronto. “They asked the diocese if we would support it. We looked into it, did some arithmetic and said, Yeah, this makes sense.”

Toronto is already a world leader in mixed-use developments: buildings that integrate multiple functions so that residents can live, work and play in the same space. The city has its share of skyscraping condos sitting atop dry cleaners or coffee shops – that’s the standard you see in many cities. But it also boasts places such as Union Park, a planned $3.5-billion complex which will soon add more than four million square feet of mixed-use space in the downtown core. Or the doughty brutalist Manulife Centre, whose dwellers have access to a movie theatre, stores, restaurants, gym and new Eataly food emporium.

Over the next decade, mixed-use buildings are set to rise in popularity: you might say they’re the environmentally correct “reverse suburbs,” in that they reduce the need for driving, put residents in closer proximity to each other and maximize resource use.

But buildings such as St. Monica’s take the concept even further, in that they prove condos aren’t just for retail outlets anymore. Today, a myriad of social enterprises – arts, religious institutions and social services – are joining forces with for-profit condo developers, creating hybrid buildings where both parties benefit.

This means that women’s shelters, churches and theatres that might have struggled for lack of government or donor support are now able to thrive, largely thanks to condo money. In turn, developers also benefit from what the agencies have to offer: valuable land, fundraising power and fascinating programming they can sell to tenants.

“This mixing of uses allows all of the parties to solve a problem for themselves in ways that they couldn’t have done on their own,” says Matti Siemiatycki, interim director at U of T’s School of Cities.

Siemiatycki has been studying these “creative mixed-use” buildings for years. An expert in city infrastructure, he believes they’re the way of the future, since they enable the city to offer a flourishing array of public and social services in spite of its density and high cost of living.

The new Creative Mixed-Use Initiative he oversees at the School of Cities is designed to “supercharge” this process – making matches between public and private partners who wish to team up on interesting, often unorthodox projects. In addition to collecting case studies and analyzing effectiveness, Siemiatycki and project manager Cecelia Pye – alongside Prof. Mark Fox and Daniela Rosu of U of T’s Centre for Social Services Engineering – recently hosted a workshop to convene potential partners. In conjunction with the university’s computer science department, they’re even developing an algorithm to optimize they best hybrids: think eHarmony, except for real estate.

“What we’re saying is, this is actually a great way to build the city,” Siemiatycki asserts. “It opens up space, and creates synergies. It maximizes values for both partners. It builds a more vibrant and exciting city for everyone: we should be doing these as a matter of policy and priority.”

The first such complex on his radar was the one now occupied by North Toronto Collegiate – Siemiatycki’s old high school. Almost 20 years ago, the century-old building was crumbling in disrepair and on the brink of demolition.

“The school board was struggling financially,” Siemiatycki says. “At that point they had a $3.2-billion maintenance backlog, and now it’s even higher.” Casting about for private investment, the board was ultimately able to sell 0.7 acres of land to Tridel, a developer. Today, the revitalized high school is connected to two condo towers; a new football field and running track is used by residents and students alike.

Once Siemiatycki saw one building of this type, he saw many more. In Toronto, there seemed to be a plethora of condo developments arising from the sides and backs of educational, religious, social and cultural institutions. Even the city’s much-vaunted film festival was granted new life through its alliance with a developer: TIFF is now headquartered in the well-known Lightbox Tower, where residents were able to take advantage of an “interconnectivity package” that provides them with cinema memberships, special parties and a private movie theatre with eclectic programming.

And Siemiatycki wasn’t just seeing condo-charity alliances, either – the massive Maple Leaf Gardens building on Carlton Street, for example, had been taken over by Loblaw, but was really too big for their purposes. So the supermarket giant joined forces with Ryerson University, to create what is now a combination grocery store and athletic centre. Fusions that were once unthinkable are now taking place.

Siemiatycki is particularly intrigued by these projects because they have all arisen organically, and often out of a sense of desperation. “They tend to be a last resort: no one is looking to do this as their first best option,” he says. “It’s complicated, it’s unpredictable, there’s a lot of uncertainty and there can be risks. The reason they get to that point is that they couldn’t have done it on their own.” The research and outreach efforts he’s now put in motion are designed, in part, to eliminate the chaotic flailing that has marked the genesis of many partnerships.

The benefit of creative mixed-use to charitable agencies is obvious: it means that social agencies won’t have to depend as much on government or donor support, which fluctuates with every election and economic downturn.

But these mergers do a great deal for the developers too, in addition to providing valuable land. Among other things, they make condo life – which can either sparkle like a granite countertop, or bring you down like a broken elevator – that much more appealing.

While it’s true that condos commonly offer amenities such as party rooms and gyms, they can also be lonely and alienating places. Green space can be scarce, and hallways barren. A 2017 survey of Vancouverites revealed definitively that highrise residents found it harder to make friends than those who lived in traditional houses. “What is it about cities that makes us so lonely?” asked a recent CBC radio report. “Just look up.”

Creative mixed-use buildings are solving that, by offering residents fuller, more interesting lives within their walls. Where the TIFF complex satisfies film lovers, the East End’s Streetcar Crowsnest condos sit atop a large theatre offering concerts and plays, as well as programming for children. At the City of the Arts on the waterfront, one will be able to take advantage of lectures, classes and gallery tours.

Siemiatycki finds the increasing level of engagement between the building’s public and private aspects highly encouraging. That wasn’t evident several years ago, when he surveyed people living in the North Toronto condo building. “The interactions there were neither negative nor positive,” he says. “It was just people living in a condo building.” Now, he says that’s changing. “There’s not just a synergy of land but a synergy of programming. That’s when you really get into the special side of city building, which is the social side.”

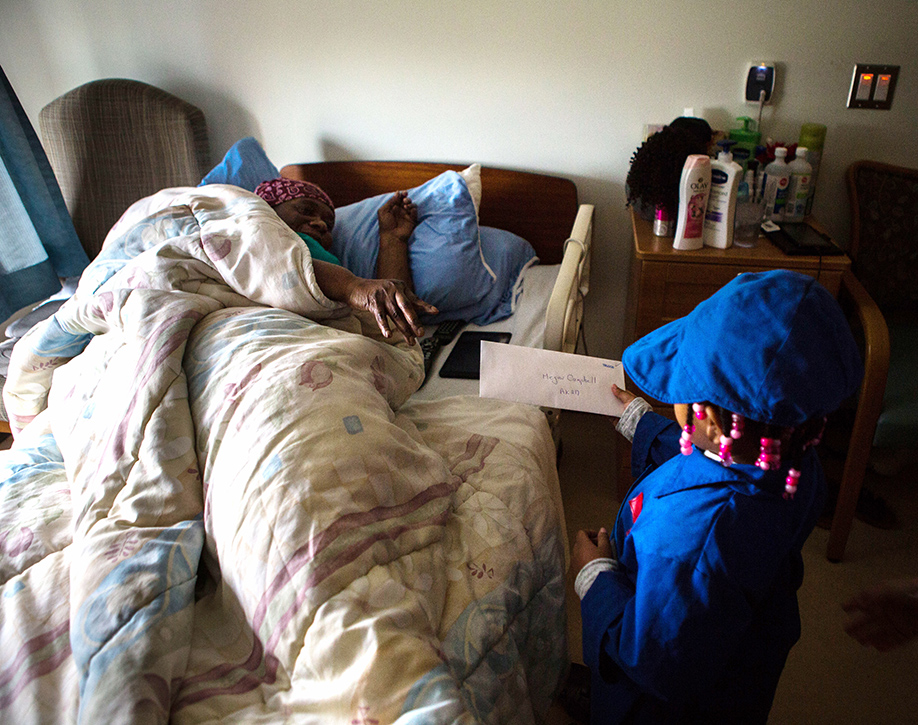

At Kipling Acres in Etobicoke, that merger of communities is not just commendable, but heartwarming. The complex houses not only a long-term care centre and community centre for seniors, but a daycare as well. The groups are fully invested in each other’s lives and activities: these include shared story times, dances and drum circles. Each week, children from the daycare put on faux Canada Post uniforms to deliver mail to the seniors.

“When they come around, the residents’ faces just light up,” says administrator Bob Petrushewsky. “Mixed-use provides opportunities for seniors to share their knowledge and life experience and interact with the younger generation. A lot of young people today may not have grandparents living nearby. Our model allows those who don’t to establish valuable relationships.”

On the one hand, creative mixed-use isn’t really such a surprising trend. Daycares, churches and theatres are all easy amenities to locate, because residents can make regular use of them. But Siemiatycki is also noticing something else that excites and reassures him.

“We’re now seeing a push toward mixed-use buildings that are the type of buildings that typically face a lot of social isolation and can be very hard to locate,” he says. These can include shelters for women, youth or the homeless, which often fall victim to not-in-my-backyard agitation on the part of neighbours.

Now, however, a select group of condo developers and residents are saying no to NIMBYism, and putting down roots not just near, but in the very same building as these types of organizations. The Red Door family shelter is one such example, connected as it is to a beautiful new condo building. And in downtown west, the building where Toronto’s water supply was once managed – known, appropriately, as the Waterworks – will open later this year, featuring almost 300 bespoke condos atop amenities that include a large YMCA, rooftop gardens and a European food hall.

Yet prior to construction, the developers recognized that the Waterworks already had a tenant onsite: the city-funded Eva’s Phoenix, which provides transitional housing and training programs to street youth.

Luxury condos and a shelter – in the same building? Not a problem, says Eve Lewis, president and CEO of Woodcliffe Landmark Properties, one of two Waterworks developers. “Quite honestly,” she says, “there were some people who were not comfortable with the concept. But I will tell you that very, very few people think it’s an issue.”

While Siemiatycki says that all these partnerships are salutary, they are also fraught with potential problems. Some have fallen apart in the planning stages. In her short time as Creative Mixed-Use project manager, Cecelia Pye has heard more than a few disappointing stories.

“Sometimes the funding may not work, especially for affordable housing. A partner may want to pull out because they don’t feel like their values are being met; it’s surprising how important values are in these partnerships. Or the timing could be off – it might be a great ghost partnership so the partners work well together but there’s no opportunity where they can actually build.”

But when it works, creative mixed-use works very well. And Milway is confident it will work for St. Monica’s and its neighbours, too.

“Even if you’re not spiritually or religiously inclined, I think you’d agree that having a church in the neighbourhood adds something special, that maybe a dry cleaner or office building doesn’t. It’s something that helps create community.”

No Responses to “ Strange Bedfellows ”

I read your article with interest. It is definitely symbiotic to merge residences with services and commercial ventures in the same building or area. However, the idea is only relatively novel. This model has existed in most cities in Europe for many decades and works very well.

Amazing concept! Thank you for your informative report.

It's about time! Mixed-use condos are a bigger version of co-housing, which for a long time I've hoped would become more common. All levels of government need to encourage these flexible approaches by reducing some of the red tape that currently prevents such developments from happening.