Just when you think you know your own language, along comes a hellwyrgen. Rob Getz ran across the creature in a 12th-century manuscript, where it was pushing some thieves suffering torments in hell into a pit of boiling tar.

As an interim co-editor of the Dictionary of Old English, a project that aims to map all of the roughly 35,000 words from the earliest form of the language, Getz is no stranger to challenging words. But this one was a stretch; not so much the first part which is obvious – hell – as the second. It looked like it might be derived directly from the verb wyrgan or wyrigan meaning “to curse, revile, condemn,” but it’s actually identical to the second part of a noun used to describe the mother of the monster Grendel in the Anglo-Saxon epic Beowulf. So, in the end, a hellwyrgen turns out to be something like a monstrous female creature from hell, or hell-hag.

Old English, which arose from the Germanic language of the Anglo-Saxon settlers who came to Britain from northern Europe in the fifth and sixth centuries, is the direct ancestor of our modern tongue. It has bequeathed us dozens of common words – from “hound” (hund) to “house” (hūs). But the language has changed so much over the centuries that anyone reading an Old English text such as Beowulf would not recognize most of the words. Even the alphabet was different, with fewer letters, a different letter for “w,” and the wonderful “eth” (ð) and the runic “thorn” (þ) standing in for “th.”

Scholars at the Centre for Medieval Studies have been working on a comprehensive dictionary of the tongue since the 1970s and, with the release of “h” this year, have now published definitions for more than half the words. Computers have made things somewhat quicker, and a digitized corpus, consisting of at least one copy of every known text in Old English (from poems to royal records), means that they can now search more easily for words and citations. But scholars still have to organize the words and define their meaning. Here there is no algorithm to aid them – just countless dictionaries, Latin sources and the lexicographer’s best intuition.

Some words appear only once in the corpus, while others, such as the Old English for “hand,” “head” and “heart” are both common and complicated. The 39-page entry for heorte (“heart”) contains more than a dozen major meanings, including the seat of love, of courage and even of the intellectual faculties.

The section on the letter “h” was particularly difficult, and not just because it begins more words than any other except “s” and “f.” It contains key verbs and pronouns, as well as the interrogatives – who, what, when, where and why – all of which began with hw in Old English. The interrogatives “are fairly uncomplicated in terms of their meaning,” says Stephen Pelle, an interim co-editor of the DOE – but they “can be very complicated grammatically.”

Old English portrays another world, a world where rain might be described as “heaven’s showers” (heofonscur), but the language is also a window into the philosophical, moral, legal and linguistic roots of our own. If we’re to understand those roots, we need to know the language the people spoke, says Getz. To that end, the lexicographers are trying to be as comprehensive as possible, picking up words earlier dictionary makers missed. “If we’re doing our job right,” says Pelle, “we should be able to catch just about every word that survives in an old English text.”

Ten Interesting Words from Old English

Hring – ring. A lot of words that today start with consonants like R, L and N began in Old English with H. Thus hleahtor (“laughter”), hnutu (“nut”) and hnappian (“to nap”). (The “h” was pronounced, at least in the early Old English period, so hleahtor would sound similar to the modern word laughter, with a huff of breath at the beginning.)

Hē, hēo, hit – the ancestors of our “he,” “she” and “it.” They occur about 200,000 times in the old English corpus.

Hūs – “house,” “building” and, in some contexts, “brothel.” The Anglo-Saxons loved compound words and hūs figures in more than 100 of them, including ealu-hūs (“ale house”), gyst-hūs (“guest house”) and pleg-hūs (“theatre” or “playhouse”).

Heoloþ-helm – a helmet that makes the wearer invisible. A demon wearing one of these figures in a medieval retelling of Genesis. He sneaks into Paradise and tries to trick Adam and Eve into eating the forbidden fruit.

Hunig-smæc – It sounds like a breakfast cereal and it certainly has a sweet side. It comes from the Old English for “honey” and “smack” or “taste,” so “taste or flavour of honey.”

Hærfest-handfull – “harvest handful,” or, the grain given a labourer as his due during harvest.

Hǣmed – marriage, but also cohabitation, adultery and even “the intercourse of animals.”

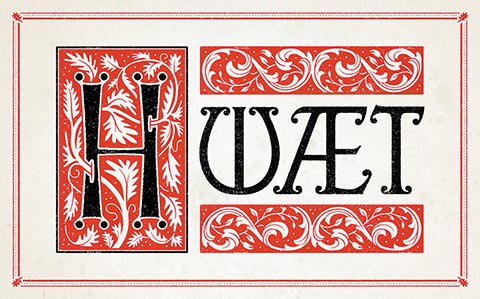

Hwæt – The most famous hard-to-define word in old English, hwæt opens the great Anglo-Saxon epic Beowulf. As a pronoun, it’s well understood; as a particle or interjection, as in Beowulf, not so much. Seamus Heaney, the great Irish poet who translated the poem to acclaim in 2000, rendered it simply as “So.” Others have gone for “lo,” “hark,” and “behold.” The DOE’s answer is: It depends. It might mean: “now,” “so,” “listen,” “why,” “now look,” “indeed,” etc. – depending on the context. The complete definition covers 26 pages.

No Responses to “ The English of a Millennium Ago ”

I was pleased to see the bold heading HWAET which translates as “what,” or, better still, “Wazzup?!” It is famously the first word of Beowulf, and still survives today in the chant of Newcastle United Football Club fans: “Howay the Lads!”

Charles Heller

BEd 1986

Toronto

A great article. It brought back vivid memories of Sister Frances Nims, who used to teach Old and Middle English (in the 1960s) when the Centre was the Pontifical Institute for Mediaeval Studies. Several of us used to sneak into her classes on Chaucer. I had the privilege of living with her for a number of years. Thanks for posting this.