Andrew Pyper proposes meeting at a Starbucks in the Queen West neighbourhood of Toronto, near where he lives. Interesting choice: It is in a fictional version of this same branch of the vast coffee-shop chain that the protagonist of Pyper’s latest novel, The Killing Circle, tries to conjure up his own work of fiction.

Since rain is expected we sit safely inside. The author of four novels and a short-story collection, Pyper, 40, explains that, unlike his protagonist, he doesn’t write much in cafés. Instead, he soldiers away in front of a computer in the basement of the modest Victorian home he shares with his wife, Heidi Rittenhouse, their one-year-old daughter and a Jack Russell terrier. “I try to start writing first thing in the morning, even before showering,” he says. “Just grab a piece of toast, throw on some sweatpants and go at it.” He laughs at the unsexy picture he’s painting: “The writing life – how glamorous, right?”

However forbidding the writing life may be, it’s the focus of Pyper’s latest book, which sets a serial killer loose in a circle of aspiring authors. Released in August by Doubleday Canada, The Killing Circle contains gleefully nasty thumbnail sketches of Toronto wordsmiths, from a ball-busting editrix at a Globe and Mail-like daily to a has-been novelist with perverted sexual tastes. Pyper skewers a Giller-esque literary award with particular delight. “This book was my most fun to write,” he says. “There are a lot of figures my colleagues will recognize.”

But the book is more than a roman à clef stocked with in-jokes for Toronto’s publishing crowd; it depicts the city’s increasingly outsized aspirations through its writers. “I was trying to capture the psychological makeup, the character of Toronto now,” says Pyper (LLB 1995). “It has finally become the world-class place that everyone was trumpeting it as 10, 20 years ago. You can be a journalist, a novelist, a documentary filmmaker, a dancer from here and do fine now.” Pyper’s own considerable success proves the point; his novels have attracted six-figure publishing contracts in New York, London and Toronto.

“There’s now this ambition here,” continues Pyper, warming to his theme. “All these people who come from Saskatoon or Moose Jaw who want to become something, sometimes without knowing what that thing is – the having of dreams and that terrible wanting to the point of toxicity. We’ve become this beacon for people to come here and attempt things. But with that comes the underbelly of failure and the frustration of not getting what you want.”

In The Killing Circle, this striving city almost becomes a character who mocks the protagonist, Patrick Rush, a failed journalist and blocked wannabe novelist, for his manifold shortcomings. Ultimately, the anti-hero’s all encompassing desire to succeed leads him into a dangerous trap. He steals a story from a member of his writing group. Soon, he and his son become the targets of a vengeful force.

This new novel – perhaps Pyper’s best – could sit comfortably between noted thrillers by Patricia Highsmith and Ruth Rendell. Or it could share space on a CanLit shelf with, say, Timothy Findley’s Headhunter and Margaret Atwood’s The Robber Bride. These Toronto-centric books also belong to that rare hybrid, the literary page-turner. “I hate when people dismiss books as just genre novels,” says Pyper, faulting the critics who slot his output only in the thriller category. “I don’t pretend to have written a contemplative, deeply philosophical book. But it’s hard to do those things that sometimes we assume are easy: to grab readers and not let them go, to keep them up at night until they reach the last page.”

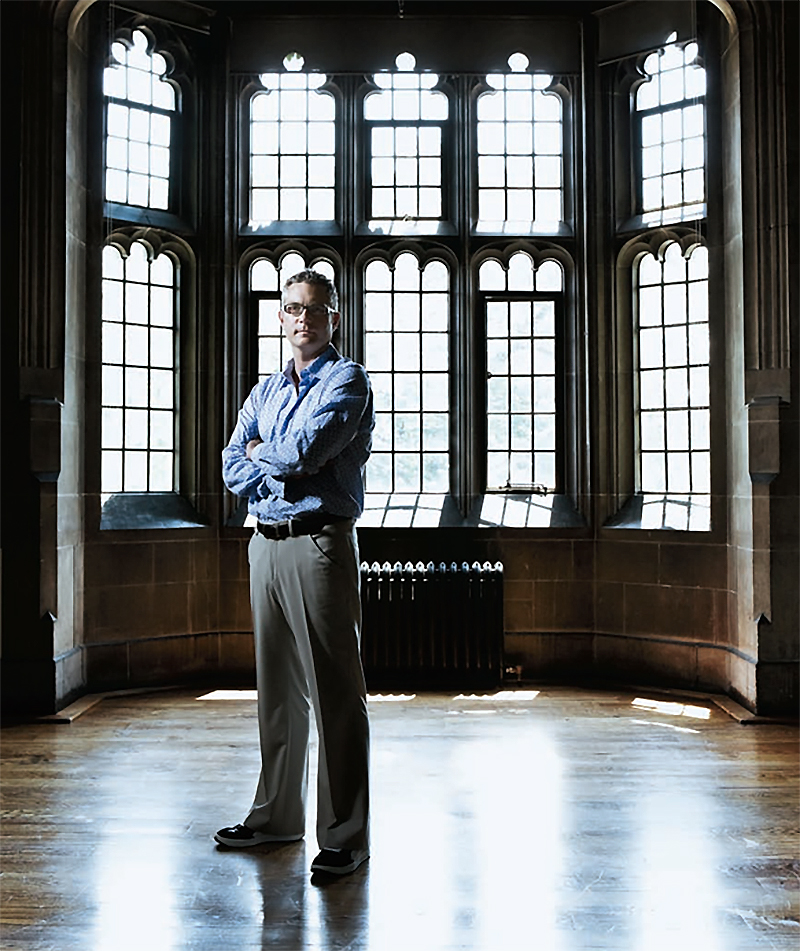

Pyper’s own life doesn’t have the makings of a thriller, but it has had some twists and turns. His light-blue tennis shirt and retro Clark Kent glasses suggest a clean-cut good guy, but this is a man who – intriguingly – has described his hometown of Stratford, Ontario, as “a great place to appear good and behave badly.”

Pyper is the fifth and final child of Presbyterians who emigrated from Northern Ireland to the festival town. His father is a retired ophthalmologist and his mother trained as a nurse. As a boy, Pyper read a lot of books and hoped he might, one day, get to write them. “I was a de facto only child, because there were eight years between me and the next brother. Like a lot of only children, I turned to the nerdier pursuits of books and writing and … making things up.”

Later, he would find other, less wholesome escapes. “There was trouble to be had,” he tells me, “small-town trouble.” He smoked pot between shifts as a waiter at a gourmet restaurant where he once served Canadian literary doyenne Alice Munro. And he gathered with his pals around impromptu bonfires on the fringe of town – until the cops showed up.

McGill and Montreal offered more sophisticated pleasures. There he pursued a bachelor’s and master’s degree in literature, absorbing the then-trendy postmodern theorems – which he occasionally sends up in his fiction. Instead of pursuing a doctorate, he opted for a law degree at U of T: “I was and am more of a generalist by nature; something about specialization strikes me as inappropriate.”

There was another factor. “So many of my biggest decisions have been based on girlfriends,” he says a little ruefully. “My girlfriend at the time was studying law. I was in love with her, and she said we’ll be lawyers together and it’ll be great.” When she broke it off halfway through his first term, he nonetheless carried on through three years of law school and a year of articling. In the mid-1990s, he was called to the bar. “I knew very early on that I wasn’t going to be a lawyer, but I was brought up to believe, wrongly I think, that once you start something you never quit – real Presbyterian stick-to-it-iveness.”

While at law school, Pyper toiled away at the short stories that would be published as Kiss Me in 1996. This collection foreshadows the gothic turn his work would take; in one story, for example, a boy is disfigured in a barbecue accident. There’s also a strikingly heartfelt rendering of a teenager’s first brush with love. All of his books have at least one relationship – between lovers, friends, father and son – of almost otherworldly tenderness.

After articling, Pyper followed another girlfriend, Leah McLaren. She was waitressing at an Annex eatery in Toronto, but decided to finish her undergrad at Trent University in Peterborough. Pyper applied for, and was named, writer-in-residence at Trent’s Champlain College. (McLaren went on to become a columnist for the Globe and Mail and write a novel herself.) Out of the time Pyper spent labouring at Trent – the “Canadian Berkeley” he affectionately calls it – would come his first big success, the internationally bestselling, multiply translated Lost Girls.

In The Killing Circle, Pyper presents the writer’s world as far from rosy. Extreme professional envy comes with the territory. When a 24-year-old woman lands a major book contract with a New York publisher (early in the novel), the deal is announced in a bar filled with would-be and has-been authors. The surge of jealousy in the room, as Pyper describes it in the book, is “powerful enough to alter the environment.”

Having succeeded as a novelist (each of his books has sold well, and international film producers have options on three of his four novels), Pyper has occasionally been on the receiving end of such envy. Early in his career, the Globe and Mail published an admiring, lighthearted profile of him and local contemporaries Russell Smith and Evan Solomon, labelling them Toronto’s up-and-coming “Book Boys.” The trio made fun of time-honoured Canadian literary tropes and traded gibes about the designer duds they were wearing. The piece raised some hackles for championing the young men as the next big thing. “We went along with the interview because we thought it would be fun,” says Pyper. “Who wants to read another profile about writers’ contemplations of war and hurt?”

In his new novel, Pyper awards success capriciously, bestowing it on his hack journalist anti-hero Rush for the story he stole from a colleague in his writers’ circle. Under these circumstances, literary success doesn’t smell particularly sweet for Rush: “It’s the fourth interview of the last five hours, and I’m not sure I’m making sense any more. A New Yorker staffer doing a 2,000-word profile. A documentary crew from Sweden…. And now a kid from the National Star who I can tell is planning a snark attack from the second he sits across from me and refuses to meet my eyes.”

Pyper has faced his share of such snark attacks – and also much praise. While British critics dollop out complimentary blurbs for each of his efforts, at home he has sometimes had a tougher ride, particularly for his sophomore effort, The Trade Mission. “He seems more intent on following Grisham than Faulkner,” local blogger Michael Bryson once sniffed.

Pyper can’t stand such snobbery, the divisions of writers into people-pleasers and artists. To his mind, too many literary types look down on storytelling, while lauding ponderously written navel-gazing. “The so-called beach reads actually take a lot of work … as much refinement as, if not more than, 500 pages about gazing out to sea and memories-of-my-grandmother.” Pyper finds it ironic that a slew of new creative writing programs are churning out writers of contemplative, “gazingout-to-sea” fiction, just as the public’s appetite for such works is drying up. “When I started working on this book I was musing about this curious social phenomenon of the declining number of readers with the corresponding dramatic rise in creative writing programs and MFA programs and church basement-how-to-write-your-bestseller groups. There’s this paradox of more and more people wanting to write, while as a society we seem to be caring less and less about reading.”

When leading a writing workshop, Pyper’s message to aspiring authors is simple: It’s the story, stupid. “I’m a big outliner,” he says. “Don’t write your way into it. Challenge and test the story; poke it.” Pyper’s advice reflects his own approach to writing. “I’m not a Virginia Woolf, doing spontaneous and poetic noodlings, letting the vibrations of the universe speak to me.”

He’s now outlining the plot for his next book. “This is the worst point in the cycle, the in-between-books stage. There’s an itchiness. You wonder: What’s next? What am I doing?” Pyper doesn’t feel good unless he’s producing at least 500 words a day from his sensory-deprivation tank in the basement. “I know percolation is necessary, but the common-sense, Northern Irish, Presbyterian side of the brain is saying, ‘Bullshit, get back to work.’”

Typically, he knows where he’s heading: In his next book, it’ll be a fictionalized version of his hometown of Stratford. Men of his vintage who went through a horrific experience together in their youth will get back together to assess how their lives are going – and to process that long-ago trauma.

“It’ll be an opportunity to explore the ways I’ve observed men of my age connect with each other, the way they maintain these relationships through first marriages and the arrival of children. They’ve been alive long enough to begin to see if their lives are going to kind of work out – or not.”

The fact that things are working out for Pyper hasn’t dulled his critique of the narrow – sometimes nasty, sometimes nice – world he inhabits. Ultimately, though, he marches to his own definition of success, hoping readers will keep turning the pages until the very end.

Alec Scott graduated from U of T’s Faculty of Law in 1994.