In a hospital, a quick and accurate diagnosis can save a patient’s life. This was never more apparent to Torontonians than during the 2003 SARS crisis. Yet pinpointing the cause of a patient’s illness can require several days of lab work, testing first for one disease, and then for another.

Dr. Warren Chan, a professor at U of T’s Institute of Biomaterials and Biomedical Engineering, has come up with a solution: a portable device that analyzes a blood sample for several different infectious agents. The best part: the test results are ready in under an hour.

Chan’s device uses sets of tiny, cell-sized microbeads contained in a vial. Each different type of microbead is filled with a colouring agent and coated with molecules of an infection that the technician is testing for. When a blood sample is added to the vial, the molecules on the microbead attach to any matching molecules they find in the blood. Then, a second colouring agent coated with the same molecules is added to the vial. With this method, an infectious agent in the blood creates what Chan calls a “colour sandwich,” or bar code. His device then reads the bar code to pinpoint the infection.

“We can’t see the infection,” says Chan, “but we’re visualizing the bar code to identify the infection.” One vial can hold as many as 15 sets of microbeads, meaning that a single test can screen for up to 15 different infectious diseases.

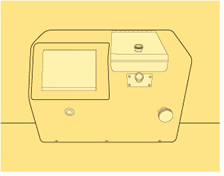

Marlex, an engineering firm in Ancaster, Ontario, has built a prototype of the device that is the size of an extra-wide breadmaker and weighs 40 pounds. Users input information through a touch screen. At the end of the test, the results flash onto the screen. Chan hopes that Marlex can eventually make the as-yet unnamed machine smaller and lighter and simpler for medical staff to operate.

The big question now is: Will it be the first to market? Chan’s lab recently received a $7-million Ontario research grant to further develop the device. “A lot of companies are attacking the same problem from a different angle,” he says. “It’s a race. But the great thing is, science moves faster when there’s competition. And regardless of who wins, it’s going to be beneficial for everybody.”