Ode to Ingenuity

U of T’s collection of scientific artifacts shows how researchers pursued discovery – and sometimes made history Read More

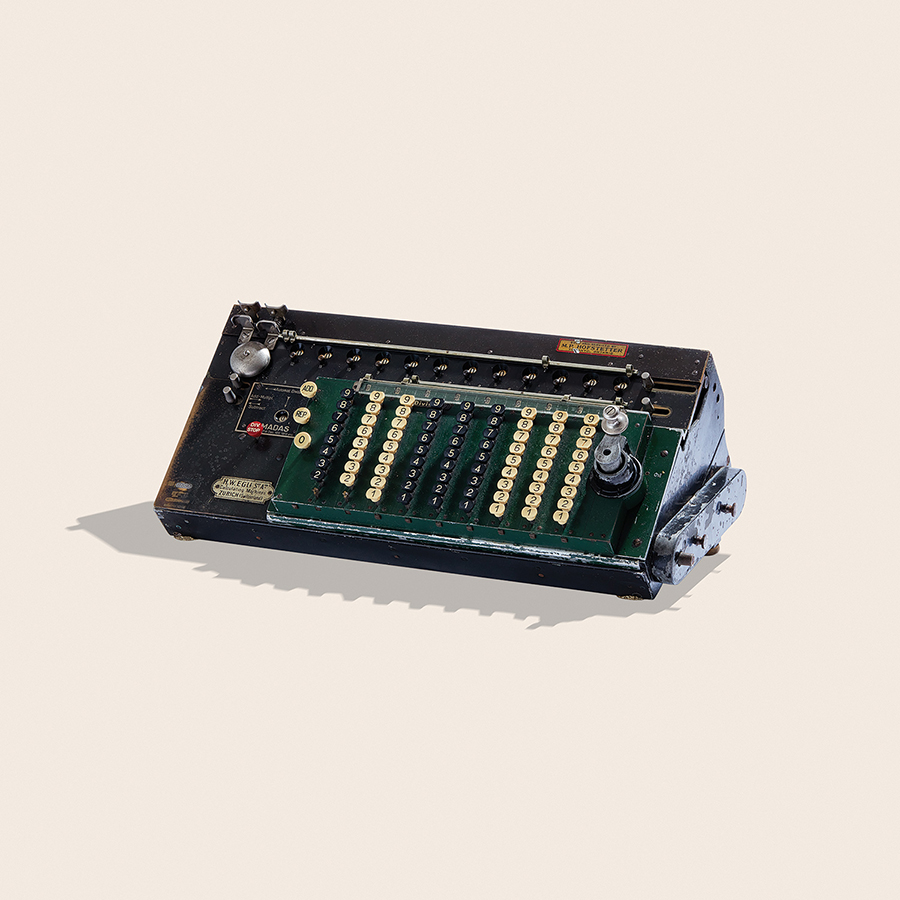

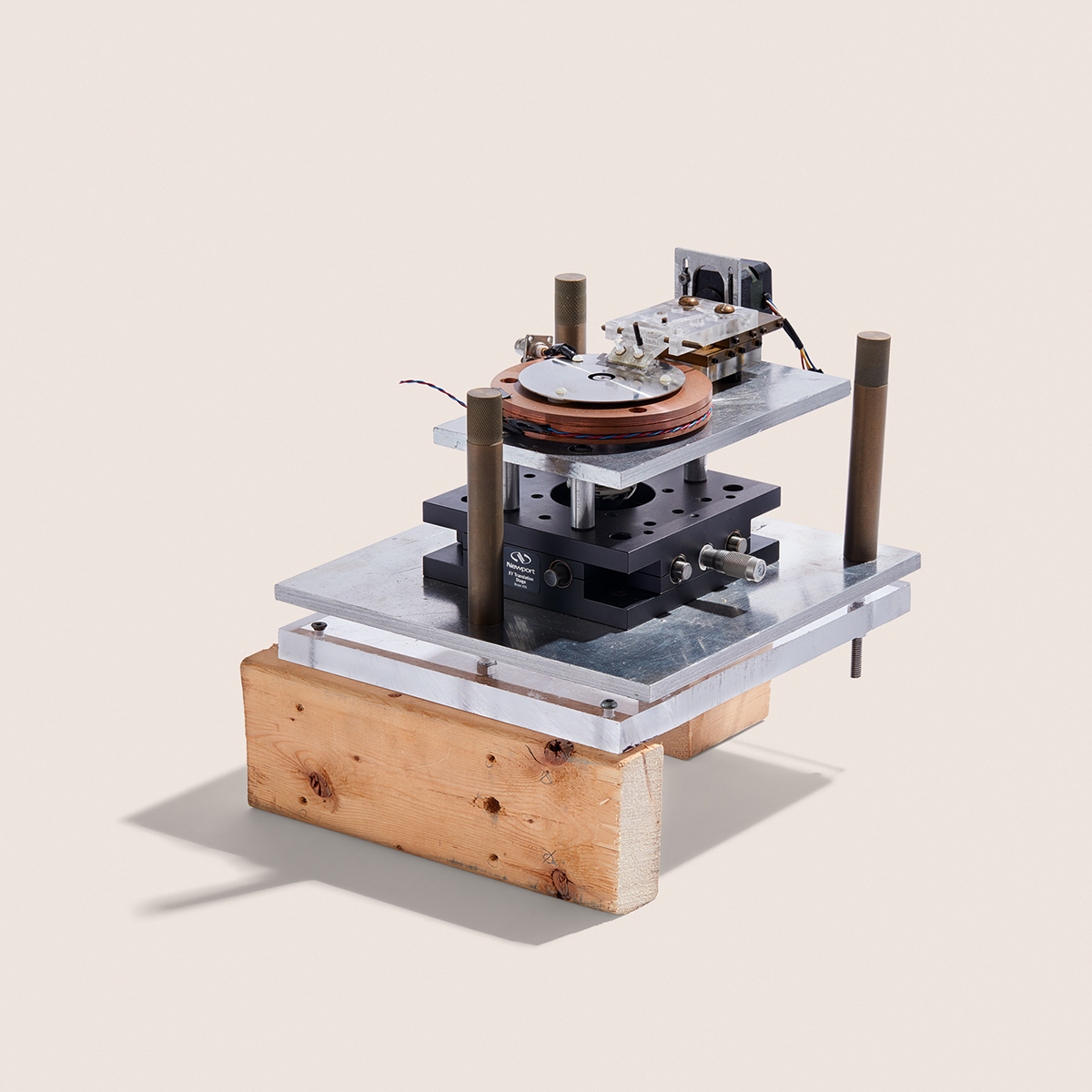

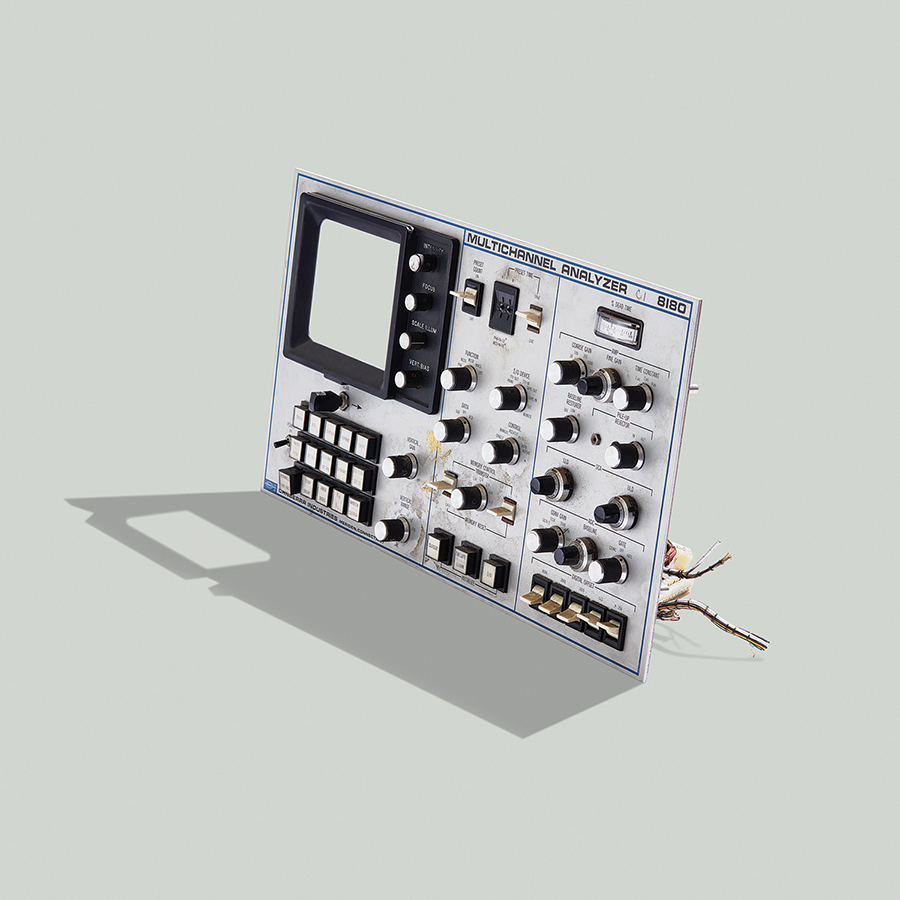

Deep underground, in the sub-basement at McLennan Physical Laboratories on the St. George campus, sits a kind of buried treasure: one of Canada’s largest collections of historical scientific instruments.

Carefully catalogued and arranged on shelves, some 2,000 artifacts, collected over four decades and covering a wide range of disciplines, reveal insights about how science has been pursued at U of T over the past century and a half: the projects undertaken – the successes and failures – and scientific trends of the day.

These artifacts – along with thousands more that remain uncatalogued in departments across the university – also tell a larger story about U of T’s role in science and innovation, says assistant curator Victoria Fisher. Some items, such as a camera lens constructed specially to photograph a 1922 solar eclipse that helped prove Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity, connect U of T with “important developments in the history of science in Canada and the world.”

Many are intriguing just to look at (see below).

The materials, which are available online with photographs and details about their purpose and history, provide insights that go far beyond what one can glean from academic articles, says curator Erich Weidenhammer. “An artifact will tell you, not only its particular intellectual and cultural context, but about the materials, design aesthetics and technology of the historical moment from which it emerged,” he observes. “Even mundane objects carry a wealth of information. A single piece of apparatus can serve as a record of an entire research program that would otherwise be forgotten.”

With such a large collection, the curators and their host department, the Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology, are fundraising for a more suitable space on the St. George campus. In the meantime, they remain on the lookout for objects of interest – especially ones that reveal something previously unknown about research at U of T. “We love that kind of thing,” says Fisher.