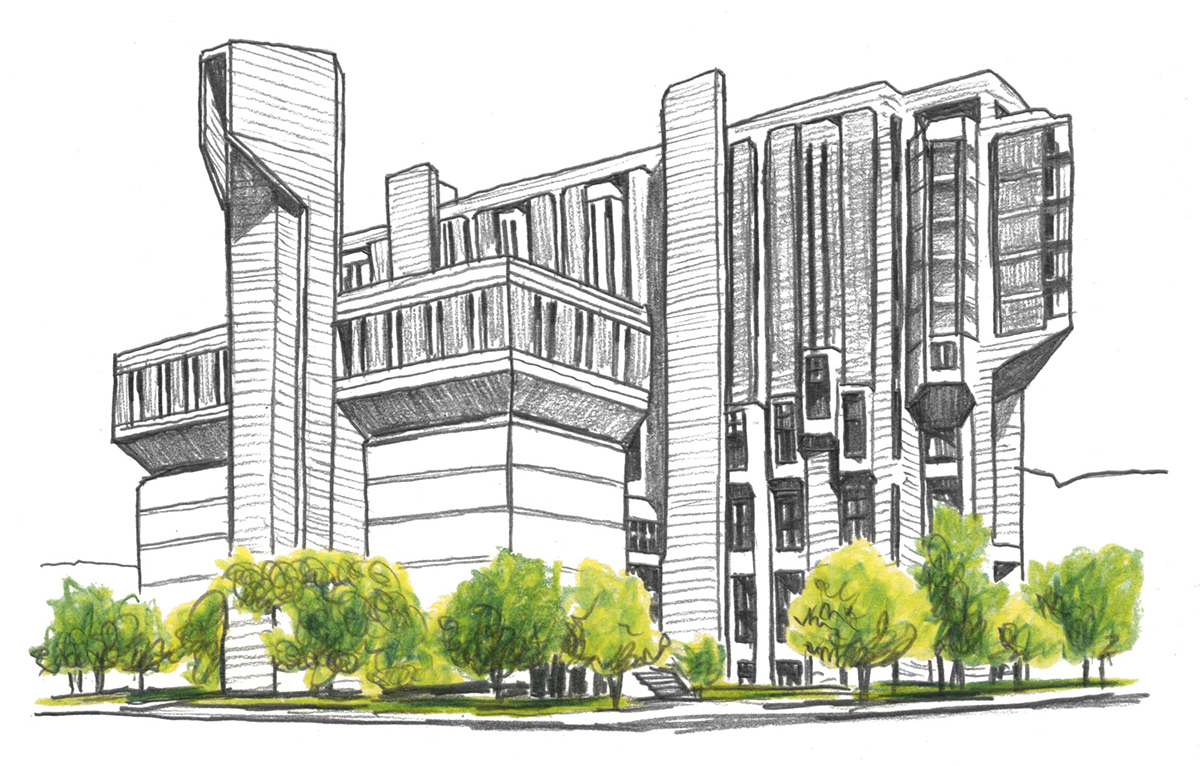

Architect Danforth Toan’s first set of design concepts, delivered in 1965, included a “city of towers” set on a broad podium, with one tower dedicated to each subject area. However, U of T’s president at the time, Claude Bissell, wanted something different from Toronto’s typical rectangular box. He requested a look that would come to be a symbol of the university and honour Canada’s upcoming centennial.

The architect suggested a triangular form, noting that it was the only shape that would provide a window for every carrel in the book stacks (a dubious claim, in retrospect). And so, a triangle it was.

The building would be immense: at 100 metres, each of its sides would be the length of a Canadian football field. Contrary to popular belief, the turret at the top of the Fisher Library – originally conceived as a bell tower – was not meant to resemble the head of a peacock or turkey; it’s merely decorative. And contrary to another urban myth, the library is not sinking, despite its enormous structural weight and that of the four million volumes inside.

When it opened in 1973, at a cost of almost $42 million (about $280 million today), Robarts – named for former Ontario premier John P. Robarts – was the largest academic library building in the world. The structure dwarfed everything around it and drew its share of neighbours’ complaints. It is still known as “Fort Book.”

But, over time, appreciation for Robarts has grown. Gary McCluskie, a principal at Diamond Schmitt, the Toronto architectural firm that designed the five-storey, glass addition that opened in 2022, has called Robarts “very well designed,” with a “rugged, expressive character.”

Indeed, now 50 years old, Robarts may finally be the right “fit” for a city that has grown up around it. And for the St. George campus, the rough-hewn giant at its core remains as important as ever – a stalwart, outsized presence in the academic life of students and faculty alike.

Did you know?

- The steps leading up to the covered terraces that separate the central building from its two wings had electric heating cables buried in the concrete to melt snow and prevent salty slush from boots from being carried into the building. They are no longer functional.

- The cloakrooms were equipped with motorized hangers and could store up to 4,000 coats. These were subsequently removed.

- The tower on the Thomas Fisher Library was almost axed to save $10,000. But the chairman of the property committee of the university’s governing board said for that price he liked it, and it was saved.

- An eighth elevator was never completed. On some floors, if you look carefully, you can see the outline of doors for the “ghost elevator.”

- Locating the escalators and elevators in the building’s central core meant that a person arriving on any floor would not be far from any part of that floor.

- At one point, to save money on construction costs, a proposal was made to eliminate the entire library science wing of the building. U of T president Claude Bissell would not hear of it. Savings were found elsewhere.

Recent Posts

People Worry That AI Will Replace Workers. But It Could Make Some More Productive

These scholars say artificial intelligence could help reduce income inequality

A Sentinel for Global Health

AI is promising a better – and faster – way to monitor the world for emerging medical threats

The Age of Deception

AI is generating a disinformation arms race. The window to stop it may be closing