In late 2019, a company called BlueDot warned its customers about an outbreak of a new kind of pneumonia in Wuhan, China. It wasn’t until a week later that the World Health Organization issued a public warning about the disease that would later become known as COVID-19.

The scoop not only gained BlueDot a lot of attention, including an interview on 60 Minutes, it also highlighted how artificial intelligence could help track and predict disease outbreaks.

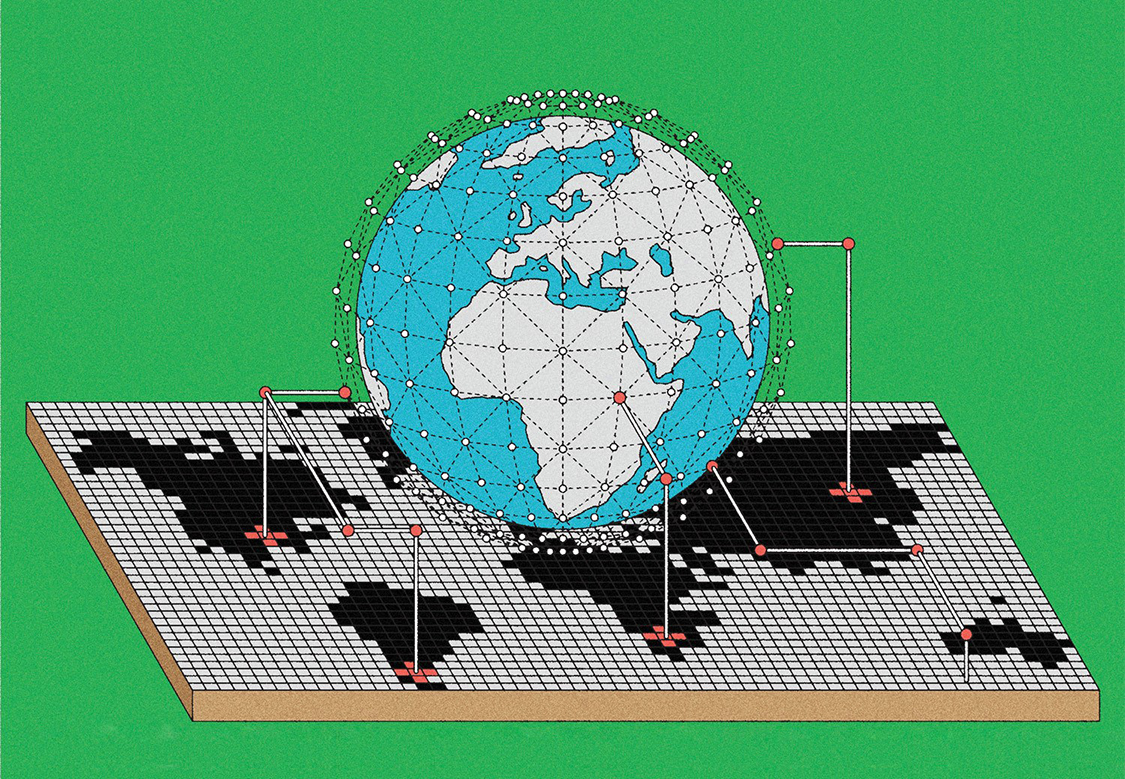

“Surveillance and detection of infectious disease threats on a global scale is a very complex endeavor,” says Kamran Khan, a professor at U of T’s department of medicine, a clinician-scientist at St. Michael’s Hospital and the founder of BlueDot. His solution is to use AI to help sort through vast amounts of information, and tag data of potential interest for the company’s human experts to evaluate.

“The metaphor of the needle in the haystack is the right one. We’re building a very big, increasingly comprehensive haystack. But identifying what is anomalous or unusual is the key, because many outbreaks appear around the world every day, yet the vast majority of them are limited in scale and impact.”

Khan’s career as a doctor is largely defined by big disease outbreaks. He was doing a fellowship in New York in 1999 when West Nile virus hit, and was there in 2001 when anthrax spores were mailed to members of Congress and the media, killing five. He moved to Toronto just months before the SARS outbreak of 2003. “Having seen three infectious disease emergencies in four years was an indication to me that in my career we probably were going to see more of these,” he says.

The heart of BlueDot’s method was outlined in a paper published six months before COVID hit. The company uses a database of news stories, created by Google and collected from 25,000 sources in 100 languages around the world – far too much for humans to sort through. Instead, an AI model trained by the company sorts through the stories and flags those that seem most likely to be about a disease outbreak of interest. To develop the system, the team ran their program retrospectively on the 12-month period from July 2017 to June 2018, and compared their results with official World Health Organization (WHO) reports for the same period.

In the paper, the researchers explain that online media covered all but four of the 37 disease outbreaks identified by the WHO, and that their system flagged all but two of those reports. Although the system missed some of the outbreaks, the ones it did detect it found much earlier than the WHO – an average of 43 days before an official announcement.

Since that 2019 paper, BlueDot has supplemented news sources with information from government health websites, reports from the medical and health communities and reports from their own clients. “We use the internet to detect early signals that something unusual is going on in a community, even before it is being officially reported,” Khan says, noting that government information is sometimes delayed – or suppressed for political reasons.

In their paper, the researchers used historical data to show that their system could work in theory. By the end of the year, when BlueDot detected COVID-19, they were able to show they could also beat official reports in real time.

More recently, BlueDot alerted clients to an outbreak of Marburg virus, which is similar to Ebola, in Equatorial Guinea in February 2023. WHO officials confirmed the outbreak with blood testing, and sent medical experts and protective equipment to help contain the disease. “We can innovate in a way that helps governments and other organizations move more quickly, when time is of the essence,” Khan says.

BlueDot isn’t the only organization using AI to help keep track of outbreaks, Khan says. The WHO has a system, and there are other startups and non-profits experimenting with the method. Khan says BlueDot offers extra value by making the information easy for governments and private clients to access, use and act upon – and by providing further analysis. “Our belief is that epidemics are a whole-of-society problem, which means that organizations across sectors need to be empowered to do their part,” he says. Since starting more than a decade ago, BlueDot has attracted 30 clients in 24 countries, both public and private. Its government clients represent 400 million people.

Khan notes that improvements in AI since 2019 are opening new possibilities for using the technology to analyze and report information. Sorting through the data generated by the system can be a time-consuming task for a human. Khan says AI is getting better at generating text and visuals such as infographics, and humans are no longer needed to create routine reports with summaries, charts and simple analysis. BlueDot is also using a new interface that allows people to ask questions about disease outbreaks in everyday language. In the past, working with the system required some computer coding skills, he says.

Soon, the company would like to be able to take its audience into consideration – for instance, writing one kind of report for a doctor, and another for a policymaker. “Generative AI is opening the door for us to be able to communicate insights to a diverse set of audiences at a large scale,” Khan says.

Rather than replacing humans, he thinks AI will complement them, allowing teams of experts to analyze and make decisions about much more data than they could otherwise.

This article was published as part of our series on AI. For more stories, please visit AI Everywhere.