Wounded soldiers drolly referred to them as “the beauty parlour” or “the tin noses shop,” a humorous defense against the terrible possibility of ever being sent to a hospital’s plastic surgery department. While trenches protected the body, anything above the shoulder was vulnerable to enemy fire and the injuries inflicted by shrapnel and machine guns were devastating. Surgical photographs from the era display young men with missing eyes, noses, jaws and, in extreme cases, entire faces.

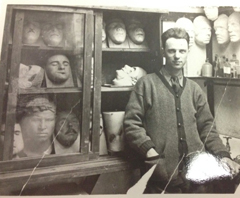

Frederick Coates was a month shy of his 26th birthday when he enlisted as a private in the No. 2 Canadian Army Medical Corps as part of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. A sculptor by profession, Coates, who later taught at U of T, used his modelling skills to help surgeons rebuild shattered and mangled faces.

Studying photographs of patients’ pre and post injury, he created plaster facial models to scale. A Toronto Star Weekly reporter recounted Coates’ process: “The plastic surgeons followed these forms minutely as they twisted human flesh into new noses and jaws. Dozens of operations were often required on one man, and all the time Frederick Coates acted as the ‘facial architect.’ The doctors knew how to graft flesh and bones; Coates knew what a remodelled face should look like.”

Coates was assigned to British facial reconstruction units at the Ontario Military Hospital at Orpington, the Westcliffe Eye and Ear Hospital at Folkstone and at the Queen’s Hospital in Sidcup, where he worked with New Zealand-born doctor Harold Gillies, whose innovative surgical techniques revolutionized the nascent field of plastic surgery. At Queen’s Hospital, Coates also worked alongside Canadian plastic surgery pioneer E. Fulton Risdon, a graduate of dentistry and medicine at U of T, who performed facial reconstruction on soldiers from Canada, Britain, Australia and New Zealand.

Following the war, Coates returned to Toronto. His work as sculptor and model-maker led to the theatre, including Hart House Theatre. In 1922 to 1923 he prepared designs for costumes and stage settings and later became the theatre’s art director. Following this stint, Coates taught model making at the School of Architecture at the University of Toronto where he remained as a part-time instructor until his retirement in 1962.

Recent Posts

People Worry That AI Will Replace Workers. But It Could Make Some More Productive

These scholars say artificial intelligence could help reduce income inequality

A Sentinel for Global Health

AI is promising a better – and faster – way to monitor the world for emerging medical threats

The Age of Deception

AI is generating a disinformation arms race. The window to stop it may be closing