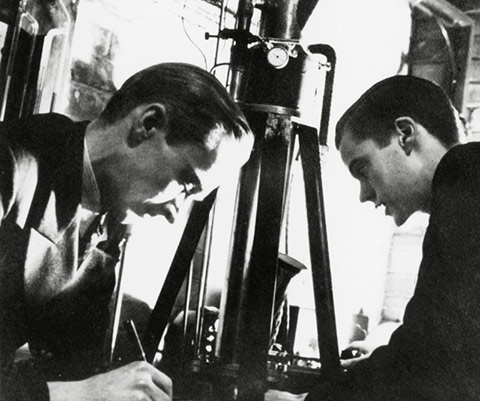

In April 1938, U of T grad students James Hillier (BA 1937 UC, MSc 1938, PhD 1941) and Albert Prebus (PhD 1940) showed their physics professor, Eli F. Burton (the moving force behind their project), what they’d been building for the last four months: North America’s first working electron microscope. Cobbled together with parts they machined themselves and sealants made by melting rubber with Vaseline, it could magnify objects 10,000 to 20,000 times (ordinary microscopes top out at 2,000 times) and was going to change fields from engineering to medicine.

Although German scholar Ernst Ruska later won the Nobel Prize for discovering the basic design principles earlier in the ’30s, “the contribution of Toronto was to invent a practical electron-focusing system that actually worked,” says Stephen Morris, U of T’s J. Tuzo Wilson Professor in Geophysics. During the Second World War, for example, U of T physicists measured molecule sizes in an effort to build better gas masks.

Eighty years later, being able to do chemical analyses at atomic scales has contributed to the explosion in nanotechnology, says Prof. Doug Perovic, U of T’s Celestica Chair in Materials for Microelectronics. For example, observing how titanium oxide changes at nanoscopic levels inspired U of T researchers working on the “artificial leaf.” And in medicine, “electron microscopes were key in describing many of the structures that make up cells,” says Prof. John Rubinstein, U of T’s Canada Research Chair in Electron Cryomicroscopy, who, with his research group, has determined the structures of numerous proteins in cells, which may help with drug discovery efforts.

Prebus went on to an academic career, building a second microscope and becoming a respected expert on the atomic structure of materials. Hillier launched the first commercial electron microscopes with electronics company RCA, helping the technology spread around the world.

Recent Posts

People Worry That AI Will Replace Workers. But It Could Make Some More Productive

These scholars say artificial intelligence could help reduce income inequality

A Sentinel for Global Health

AI is promising a better – and faster – way to monitor the world for emerging medical threats

The Age of Deception

AI is generating a disinformation arms race. The window to stop it may be closing