The Spy Among Us

U of T prof Pat Bayly headed up North America’s first spy school and developed an “unbreakable” cipher machine during the Second World War Read More

Pat Bayly (BASc 1930) landed in New York on December 7, 1941, the day the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor and brought the United States into the Second World War. After a whirlwind tour of top secret British intelligence installations, he had crossed the Atlantic aboard a converted banana boat — the only transport available to him in wartime — eager to take up his position as assistant director of the British Security Coordination (BSC) agency, the American wing of the Secret Intelligence Service. There, he commenced working for one of the greatest espionage operations in British history.

A short time before, Bayly had been a professor in the department of electrical engineering at the University of Toronto. His specialty was wireless telegraphy — radio communication by means of Morse code or other coded signals. Such was his expertise that Bayly had taught his first course at U of T while still an undergraduate… to rave reviews. Students described him as a “knock-out” professor whose “interesting and imaginative” lectures were “much anticipated.”

What no one anticipated, however, was how this comparatively quiet academic life was about to be upended. In the fall of 1941, Winnipeg-born “superspy” Sir William Stephenson (aka Intrepid) — who many claim as the real-life inspiration for James Bond—tapped Bayly to head up communications for the newly established BSC agency. Canada supplied Stephenson’s secret organization with numerous experts, but Bayly stood out. A fellow operative described him as “one of the most brilliant Canadians” and credited him with adapting existing ciphering machines so they could handle the immense number of coded messages passing daily between London and New York.

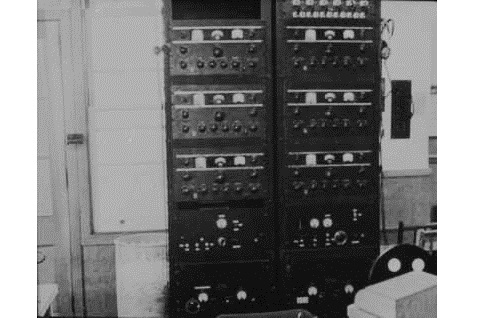

The adapted ciphering machine was Bayly’s Rockex (purportedly named for the dancers at Radio City Music Hall). When war broke out, Britain and American cypher technology had not progressed much past what was used in the First World War. The Rockex was a great leap forward. It changed words into code and code into words at an average of a million words per day and cut overseas communication time from hours to seconds.

Stephenson was so taken with Bayly’s invention that he summoned experts at England’s Bletchley Park—where Alan Turing and others broke the Nazis’ Enigma code—to come at once and see it in action. Soon after an elite team of cryptologists (including Turing) arrived in New York to study the miracle machine. Duly impressed, the team made the Rockex a critical link between New York and Bletchley. With encryption understood to be “unbreakable,” Allied use of the Rockex rendered German tapping of transatlantic lines effectively useless.

Bayly was also put in charge of communications at Camp X, near Oshawa, Ontario. Currently the focus of a hit CBC show (X Company) and a popular children’s book series (Camp X, by Eric Walters, BEd 1990), Camp X is no longer Canada’s best-kept secret. But back then, North America’s first spy school trained hundreds of Allied secret agents in the dark arts of espionage—reportedly trainees who completed the “assassination and elimination” program could kill a man with their bare hands in 15 seconds.

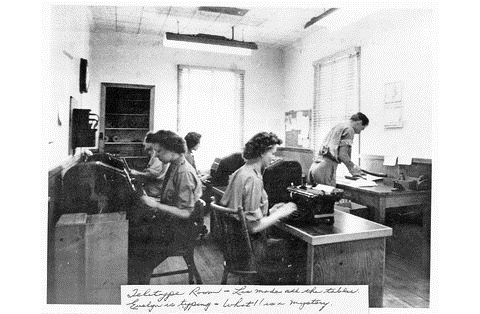

One of the most critical components of Camp X was Hydra (named after its three large antennae), a covert communications relay station set up by Bayly. Hydra connected Allied agents around the world; messages dispatched from London to Washington, South America or New York (and vice versa) came through Camp X. By mid-1944 the station was sending 30,000 and receiving 9,000 dispatch groupings daily—the bulk of Allied communications in the Western Hemisphere.

Bayly’s work doubtless facilitated the Allied victory in the Second World War. However, the full impact of his efforts may never be known. In the years following the war, most documentation related to the agency’s activities was either suppressed or destroyed. And Bayly seldom spoke of his wartime involvement. When peace came, he resumed teaching at U of T. In 1946 he formed his own company, Bayly Engineering Limited, located first in Oshawa and later in Ajax, where in 1955 he became the town’s first mayor. Bayly also played an instrumental role in securing the obsolete facilities of Defence Industries Ltd. in Ajax, the largest munitions plant in the British Commonwealth, as temporary accommodations for U of T Engineering’s overwhelming post-war enrollment. He died in March 1994, just shy of his 91st birthday.

Bayly’s service was recognized with the Order of the British Empire in 1946 and fellowship in the Institute of Radio Engineers in 1947. The University of Toronto inducted Bayly into its Engineering Hall of Distinction in 1989. In 2016, work will commence on Pat Bayly Square in the heart of downtown Ajax. Of all the accolades, Bayly would probably most appreciate what children’s writer Roald Dahl (who spent time in New York and at Camp X) had to say about his contribution: “The only telegrams that didn’t leak were ones… sent from New York. [They] had all these fantastic coding machines up there.”

With files from Lynn Philip Hodgson, author of Inside Camp-X. For more information on Camp X, visit camp-x.com. Readers who wish to learn more about Pat Bayly may want to check out Bill Macdonald’s book, The True Intrepid.

No Responses to “ The Spy Among Us ”

Thank you for mentioning my book. For more information about Mr. Bayly, check out The True Intrepid or the Intrepid's Last Secrets. When Alan Turing came to North America during the Second World War to work at the Bell Labs, he stayed at Bayly's place in New York.

Great article on an interesting topic: a real Canadian success story! It was the inspiration behind my novel Unknown Bravery. The history of Camp X is compelling and should be better known to all Canadians.