In a bid to lower the number of people dying from opioid overdoses, the Ontario government is funding naloxone, a drug that temporarily reverses the effects of an overdose. Some bars and public places now keep a kit on hand so that people can administer the drug in case of emergency. But it’s not easy to sort through the kit’s items, load the needle properly and follow complicated instructions when you’re in a panic.

In April, three U of T engineering science students – Jacqueline Fleisig, Cassandra Chanen and Zhengbang Zhou, who are now in their second year – reimagined the province’s current naloxone kit as part of a design course. Their proposed changes would make the kit more intuitive and user-friendly – which could mean naloxone is administered twice as fast, and accuracy of delivery and safety are increased.

The students focused on a design for people who have never used a naloxone kit, and who find themselves in a social setting with someone overdosing on any drug laced with fentanyl, says Fleisig. “The current [government] kit services people who have experience with needles or who are expecting to encounter opioids one way or another.” But it’s not really servicing the inexperienced – and as the volume of drugs unknowingly laced with fentanyl has increased, this demographic is growing, she says. Adds Chanen: “Regardless of design, just having access to the kits is very important. But if it can be made better and more usable, that could help save lives. Small things can do that.”

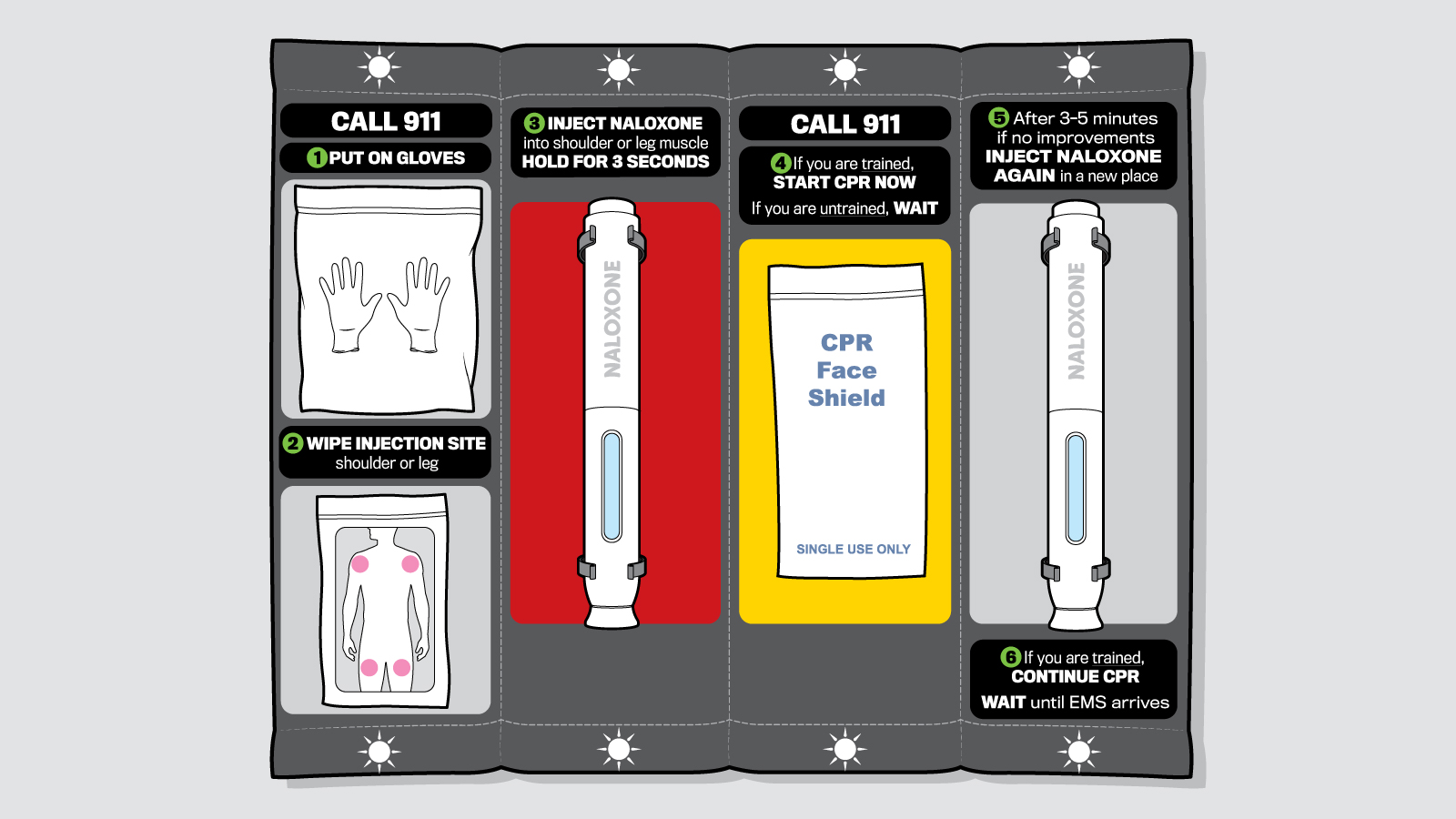

The current naloxone kit has a hard-shell case: open it up, and everything is a jumble that you have to sort through, which can be confusing and time-consuming. The students created a fabric kit that rolls out, with all items attached to the fabric in order of execution. Presented left to right, with clearly numbered instructions – written in short phrases – the intuitive layout allows the novice to grasp every step quickly. Another good idea: There are several reminders to call 911, which is crucial, as the naloxone wears off quickly.

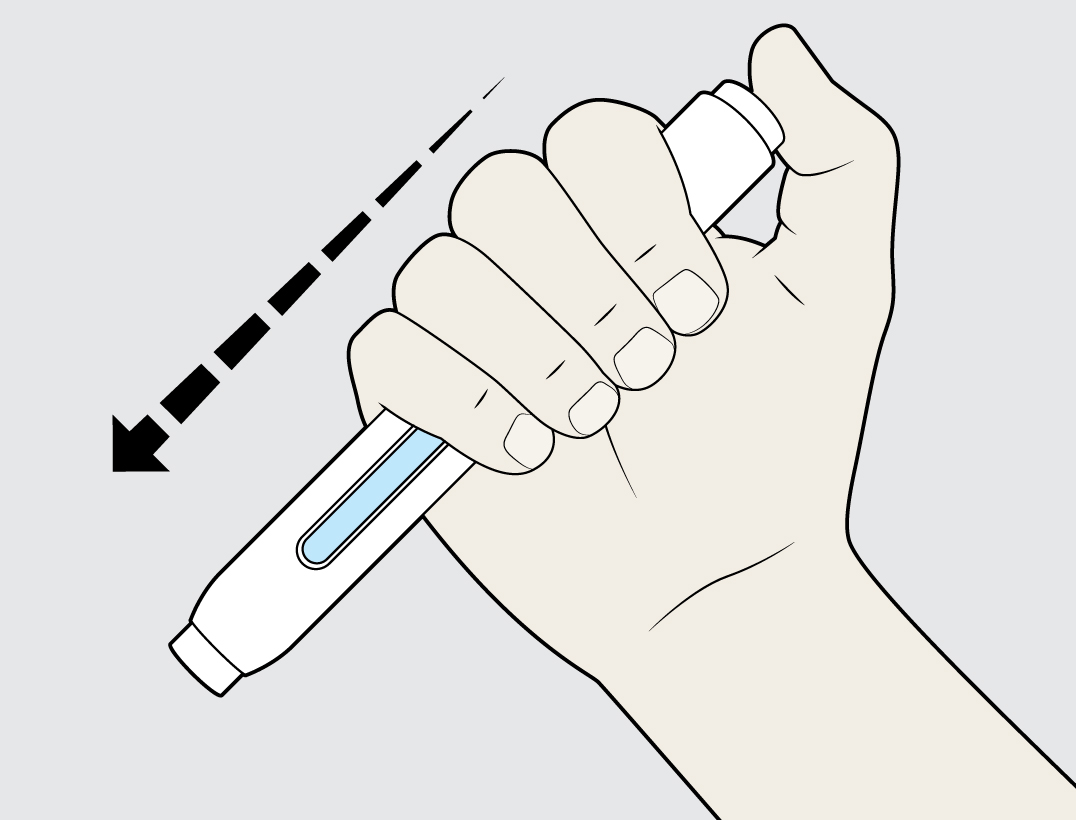

Shaky hands from nerves or stimulants might make loading a needle difficult – and might lead to safety issues: “It matters a lot whether you have air bubbles, because they obviously cause issues in your bloodstream,” says Chanen. So the students proposed an auto-injector – a needle preloaded with naloxone – which eliminates a step, decreases precision required and increases speed.

Colour coding was used to highlight priority. Red, which symbolizes emergency, was used behind the needle, for example, which is the most important object of all. A black background provides contrast to highlight directions.

Clips not only keep each item in place, but allow them to be removed vertically or horizontally – whichever is easier for the user. It’s a small thing that ensures the pieces can come out easily and simply without getting caught. (In the current case, all items are clumped together in netting.)

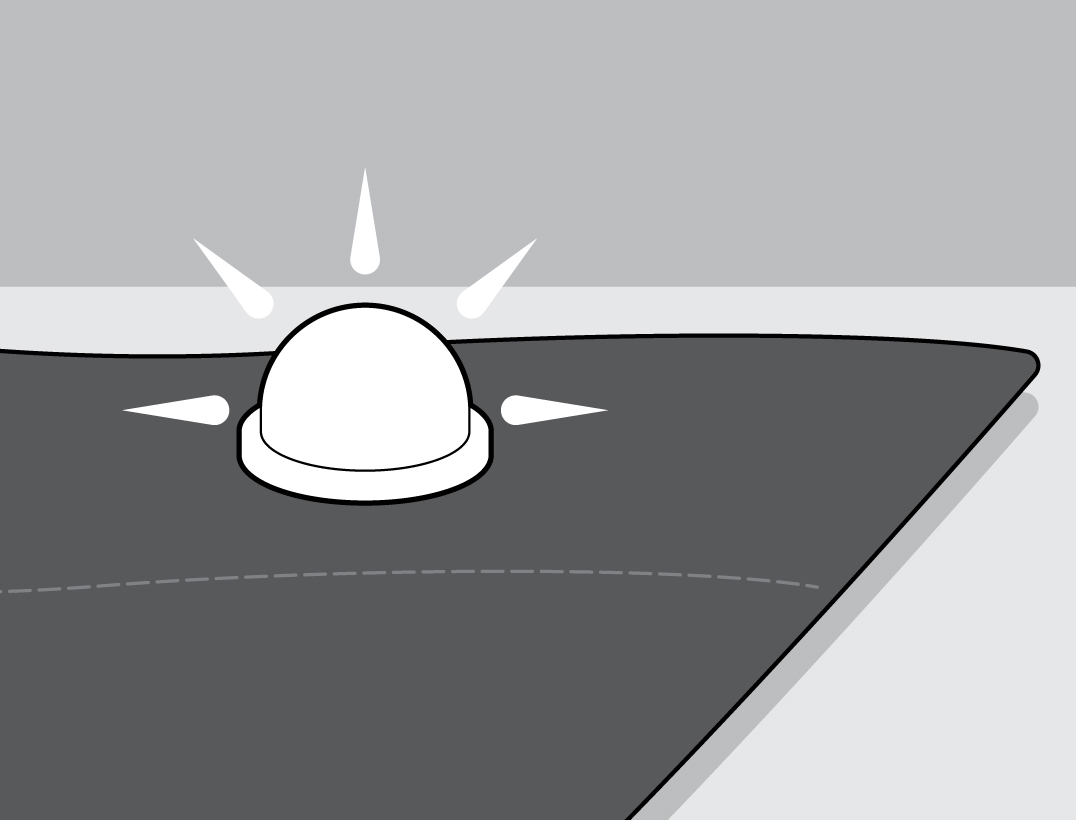

Although lights didn’t make final design, ideally, the group would have embedded them into the kit to provide visibility and reinforce order of operation. The backlighting would come in handy at a club, bar or concert where lights are dimmed.

3 Responses to “ In the Event of an Opioid Overdose… ”

Very cool! Nicely done: this is timely, useful and will save lives.

Well, yes. Except that "air bubbles" are not a significant concern, and an auto injector costs thousands of dollars, whereas a generic naloxone ampule costs around $20. And pre-loading a syringe would render its contents non-sterile unless you use it within a short period of time. And current government-issued kits contain intranasal naloxone, avoiding this perceived problem. And we should be giving rescue breaths for a witnessed overdose rather than CPR unless the heart has stopped. Regardless, any effort to make the process easier to understand and perform in an emergency is welcome.

Cassandra Chanen responds to @Kelly

When we first designed our kit last spring, nasal spray hadn't yet been approved for use in Canada. Our testing told us that the current syringes were too difficult for untrained people to use effectively in stressful situations. While auto-injectors are extremely expensive and preloading a needle can affect the sterility of the needle's contents, we offered up an auto-injector or preloaded needle as a suggestion, with the hope that the cost or lack of sterility could be addressed through future design.

As for the steps for CPR, these came directly from the original government-issued instructions. Traditional CPR involves both rescue breaths and chest compressions.

We recognize that, as second-year engineering students, we are not experts. We appreciate the feedback. The new intranasal spray kits are a great step forward, and we hope to see many more steps taken to address the usability of the kits -- and, ultimately, save lives.