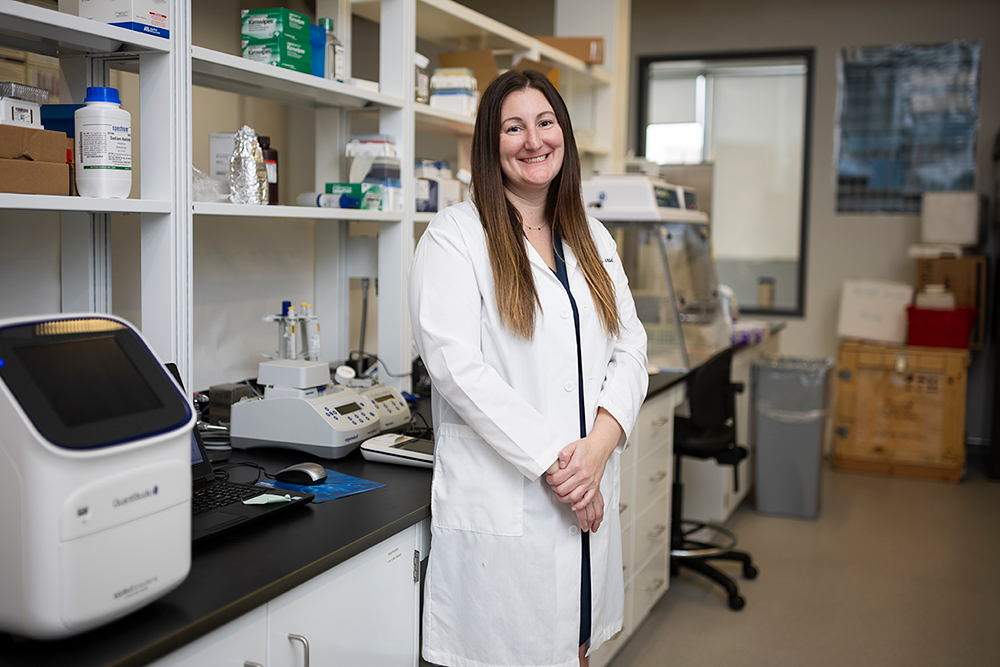

Nicole Novroski is a forensic geneticist and assistant professor in the forensic science program at U of T Mississauga.

In the 1970s and 80s, a violent offender who became known as the “Golden State Killer” committed more than 100 crimes across California. The cases became famous because they remained unsolved for decades, but also because they were the first criminal cases in which investigators used a certain kind of DNA evidence to catch the perpetrator.

Police had recovered DNA from the crime scenes but had never been able to connect the biological evidence to a person of interest. That changed in the 2010s with the arrival of free public genetic databases where people began uploading their DNA profiles (obtained from companies such as 23andMe and AncestryDNA) in the hope of finding relatives.

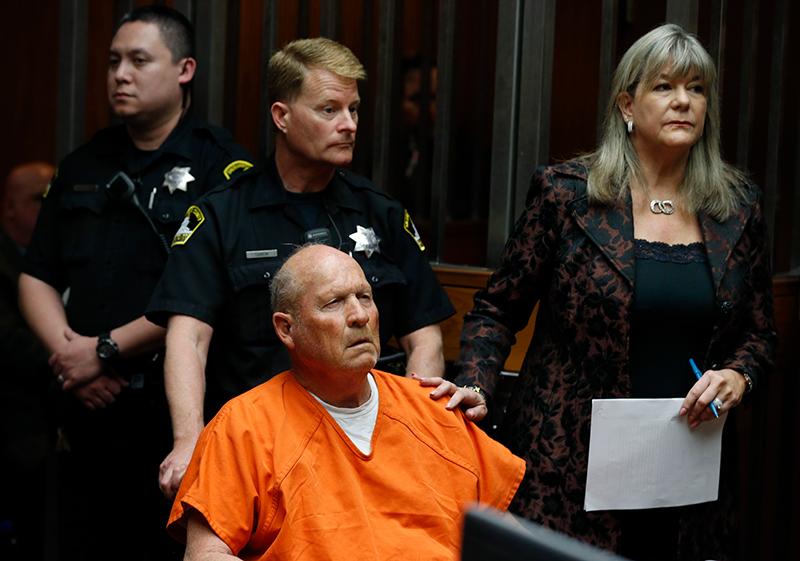

In a process known as forensic genetic genealogy, investigators pursuing the Golden State Killer were able to link DNA from the crime scene evidence to individuals who had made their genetic information available through one of these public genetic databases. Many of these individuals, it turned out, were relatives of Joseph James DeAngelo, a former police officer who then became a suspect in the case. While following DeAngelo, investigators obtained his DNA by surreptitiously collecting a discarded item. The DNA sample was then tested and compared to the evidence from earlier crime scenes.

DeAngelo’s arrest and conviction, in 2018, when he was 72, marked an enormous victory for California law enforcement and the affected victims and their families. But it also raised concerns about police using genetic data from a public source that was not originally intended for crime solving.

The following year, police in Burnaby, B.C. expressed interest in using the same technique to narrow down the pool of potential suspects in a high-profile homicide case in which more than 2,000 people had been investigated. Media asked me about the ethics of this practice, and particularly whether I considered forensic genetic genealogy a violation of privacy.

The answer is complicated.

Members of the public voluntarily send their biological sample to a company for DNA analysis, in the hope of gaining information about their family ancestry. Then, it is their decision whether to upload their individual DNA data to one of the free genetic genealogy databases, knowing that these databases are accessible to anyone.

Investigators are simply making use of this same public tool. There is no privacy violation because people choose of their own accord to make the genetic information available that can lead police to identify a potential person. Also, it isn’t solely the genetic information that makes this identification possible. The genetic record is used in combination with other genealogical work to help narrow down the number of people of interest and potentially identify a suspect.

In a nod to concerns about privacy and ethics, though, law enforcement officials are required to jump an additional hurdle. They must use a portal of the database (in this case, GEDmatch PRO) that requires a paid membership available only to certified police and forensic teams.

Through this membership, professional users have access to all of the system’s data to aid in the identification of human remains. However, if the goal is to identify the perpetrator of a crime, professional users can only search data for which the files’ owners have “opted in” to permit use by law enforcement.

The benefits to this kind of investigation, on the other hand, are immense. When genetic matches are made – either directly or through genealogical links – they can help close a decades-old investigation, provide closure for the family, catch the culprit, and prevent further grievous harm or loss of life. This is a tremendous feat.

And it’s not always a high-profile case involving dozens of crimes: Some of the cold cases that forensic genetic genealogy has helped resolve were committed by individuals who never became serial offenders. With so short a trail of evidence, these perpetrators may never have been identified without the use of this powerful tool. Given its successful track record, I expect we will see its increasing use for investigating violent crimes from both past and present.

This is why it’s all the more important that we maximize the scientific and investigative potential of the technology while ensuring that those who use it follow all the rules. It’s vital that, as members and advocates of the criminal justice system, we maintain our integrity and serve society by always following a best-practices approach when pursuing leads.