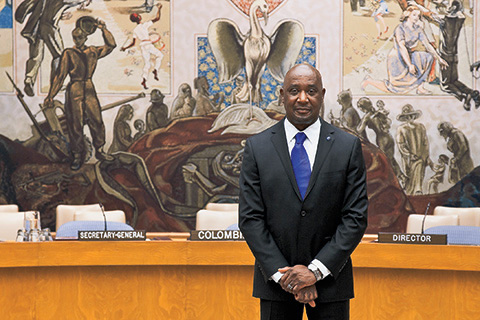

During his career in Foreign Service, Desmond Parker travelled the world. These days, the world travels to meet him.

As chief of protocol for the United Nations in New York City, Parker (BA 1976 UTM) ensures that the UN implements its protocol policies in an orderly fashion and in a way that is acceptable to all 192 member states, as well as UN agencies and intergovernmental organizations. He and his team set the ground rules for how discussions take place, how agreements are arrived at and how people interact at the UN – and, by extension, the international community. During last year’s General Assembly, for example, Parker’s team provided protocol accreditation for 8,500 delegates – co-ordinating meetings, photo-ops and seating arrangements, among many other functions. “We have to make sure that when they get here, they’re comfortable,” says Parker, who was appointed in May 2010. “Then they can focus on substantive issues, and not issues of personal well-being.”

Born in Trinidad and Tobago to a police officer and homemaker, Parker decided to study languages at U of T Mississauga (then Erindale College). “I had family in Toronto, and I thought it would be one of the easier places to settle,” he says.

Impassioned by travel and fluent in both French and Spanish, Parker earned a master’s degree and started a career teaching French in Nigeria. But after 10 years, the world traveller longed to return home. “I was 35, married with four kids. I thought, ‘You’re a young man, and you can still do something else for yourself.’” He then accepted a post with Trinidad and Tobago’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Early in the 1990s, however, Parker’s peaceful homecoming was interrupted. A coup d’état erupted in Haiti, and he joined the International Civilian Mission to monitor the human-rights situation in the region. In 1996, a move to Liberia saw him working as a UN peacekeeper in that country, then in the midst of civil war. He spent six years there, engaging in peace-building after the conflict concluded.

Parker’s work has required great courage at times. He has gone for long periods without basic amenities, and endured forced separations from his family, who were in the United States during much of the time. He says it’s all part of his job. “When you commit yourself to working for the United Nations, especially in peacekeeping, you have to have a passion and an appetite for working in dangerous situations far from home,” says Parker, 61. “There is so much suffering in the world – and there has to be a group of people committed to public service, so that the rights of disenfranchised people are protected.”

Parker’s current job also affords him an extraordinary window onto different cultures and customs. “Politics plays a big role in showing the differences between people,” he says. “But there is much more that unites human beings, than divides them.”

Recent Posts

People Worry That AI Will Replace Workers. But It Could Make Some More Productive

These scholars say artificial intelligence could help reduce income inequality

A Sentinel for Global Health

AI is promising a better – and faster – way to monitor the world for emerging medical threats

The Age of Deception

AI is generating a disinformation arms race. The window to stop it may be closing