I was 43 years old when I had my first piano lesson. Forty-three years old, newly divorced and the mother of a three-month-old baby. I cannot remember why I decided to take up the piano right then; there is no obvious reason. What I do know is that I’d been crying for an entire year. Crying in public as much as in private; crying in such a way that led my family doctor to say: “You do know this isn’t normal, don’t you?”

I didn’t know what was or wasn’t normal any longer; my former life had been detonated and I was stumbling, lost in its ruins. I couldn’t write and I couldn’t read. Therapy wasn’t helping and neither were antidepressants. Perhaps in some deeply buried part of my unconscious I thought learning to play the piano might just help.

And so I arrived at the east end Toronto doorstep of a young woman with a Russian name and a giant Bouvier who occupied most of the living-room carpet. An eight-year-old boy was finishing up his lesson, his mother perched eagerly nearby in a chair.

My new teacher wondered what experience I’d had as I sat down on the piano bench, perhaps assuming, given my age, that life had taught me something relevant to where I found myself. I remembered the treble clef from early years spent playing the violin, but had no familiarity with the bass. I’d learned the alto clef when I moved on to the viola, which I played up until my first year of university. I had always felt aware of my limitations though, never having studied music theory. Music seemed to have turned into math at some point and I have never been good with numbers.

What did I want to achieve by taking piano lessons at this point? I knew I wasn’t interested in doing scales, in participating in recitals and measuring progress through conventional grades. I wouldn’t be striving to be good. I didn’t even aspire to technical proficiency. I think I just wanted to be able to read the notes and make my hands comply and get from the beginning to the end of a song.

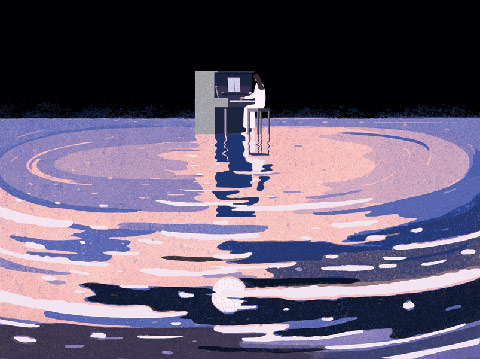

We started with some sight reading from a book for adult learners that I’d brought along. I plunked my way through the pages, naming the notes, communicating them to my fingers, my left hand lagging behind my right. It took such focus and attention I could almost see new neural pathways being created in my brain. For 45 minutes once a week I was physically, emotionally and intellectually challenged in a way that commanded all my resources. For 45 minutes once a week I did not cry.

And then we got to every beginner’s standard: Bach’s “Minuet in G.” After weeks spent practising the Minuet, I declared my hatred of the piece. It wasn’t how long I’d been at it – I’d hated it from the first moment I put my fingers to the keys. One of the nice things about being an older student, perhaps, is having the temerity to say such a thing.

What we realized, as we flipped through the rest of my book for adult learners, is that I was only interested in music in minor keys. Anything in a major key just felt too bright, too alarming, too false for my mood. My teacher immediately suggested a piece I might like: “Ivan Sings” by Aram Khachaturian, with its three moody flats. I didn’t even know it was possible to fall in love again, but I was smitten with it from the start.

Over the course of the next few months I worked on the first half of the piece. But then my teacher got a new job and she and her Bouvier left Toronto, headed for Montreal. While she recommended a new teacher, I already knew that the elements that went into creating the particular alchemy of these lessons couldn’t be replicated elsewhere. But Ivan and I would keep each other company for years as I worked out the rest of his story on the old piano in my living room. After “Ivan Sings,” “Ivan Is Ill,” but shortly after that, “Ivan Goes to a Party.” I have accompanied him into C and E major.