Woody Allen once wrote that good people sleep better at night than bad people do – but the bad ones enjoy the waking hours much more.

Not so with U of T’s devoted crop of 2006 Arbor Award winners, all of whom lead lives they enjoy, largely because of their virtuousness – not despite it. The awards, now in their 17th year, honour alumni and friends of the university whose volunteer efforts support many valuable programs.

As is typical, this year’s winners – all 100 of them – are a diverse group, motivated to see an already effective university live up to its own considerable standards. As winner Susan Eng notes: “I used to think they wouldn’t need me here. But when you get closer, you realize that even a very good university can always improve.”

In addition to successful careers, the seven Arbor Award winners profiled here possess community-building experience that extends beyond their commitment to U of T. Accordingly, they have valuable lessons to teach alumni who may want to get involved in volunteering, but aren’t sure of the best way to go about it.

Bill Ostrander, for example, stresses the importance of social networking. Verna and Jim Webb are models of inclusion and friendship. Susan Eng’s focus is accountability, and asking hard questions. George Mowbray reminds us of the need to respect the past, while Bonnie Stern and Raymond Rupert are caretakers of the future. From all of them we learn that doing good, more than anything else, means doing.

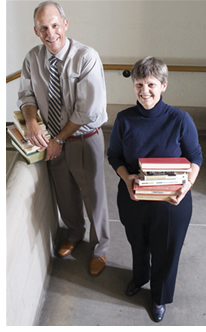

Verna and Jim Webb

Every October, the vaulted ceiling of Trinity College’s Seeley Hall looks down on a feeding frenzy that might have surprised the restrained seminarians of years past. This is the Trinity College Book Sale – a five-day extravaganza that sees bibliomaniacs lining up in the predawn hours to get a crack at some 100,000 used tomes, ranging from dollar paperbacks to precious rarities.

It couldn’t happen without Verna and Jim Webb (BA 1965 UC, MA 1969, PhD 1972).

The retired schoolteachers act as co-treasurers of Trinity’s Friends of the Library committee. Over the course of the year they are involved in most aspects of the sale’s myriad needs: pricing, sorting books into more than 60 academic and popular categories, hauling boxes, setting up tables and communicating with the hundreds of volunteers who make the sale run smoothly. After the money is counted (last year’s sale reaped $125,000, all of it designated for Trinity’s library), the Webbs occupy themselves with the dispersal of leftover books to dealers or other interested parties. In the eight years since they first got involved, their infectious camaraderie has attracted many likeminded helpers to the task.

“You just have to be welcoming, make people feel included,” says Verna, whose Tuesday sorting group is a model of relaxed conviviality (complete with birthday cake, when called for). The Webbs were brought on board by Jim’s former colleague Charles Laver, who’s worked on the sale for 28 of the event’s 31 years. Friendship and word-of-mouth are the twin engines on which this massive undertaking runs. “Books come from many different sources,” says Jim. “Retired professors, members of the Friends of the Library, friends of members of the Friends of the Library…. You never know where the next treasure will come from.”

Jim attended University College, although the Webbs’ son Todd (who now teaches history at Laurentian University in Sudbury) graduated from Trinity in 1997. The whole family, of course, loves books, with a taste for history and biographies. Do they avail themselves of the many books on offer? “We’re trying not to buy many more at this stage,” laughs Verna. “Our house would sink!”

George Mowbray

The Hall of Distinction, on the second floor of the Sanford Fleming Building, is lined with elegant plaques that tell the stories of some remarkable engineers. Their biographer isn’t an engineer himself, but a former economist, entrepreneur and technical writer whose mission is to foster dreams. “These accolades are designed to inspire young engineers as well as to honour the recipients. Students can look at them and say ‘hey, maybe I can do that too,’” says George Mowbray, who earned an MA in political economy from the university in 1948.

Mowbray, the son of an electrical engineer, started corporate writing while working as a management consultant in 1959. Sixteen years ago his friend, engineer Bob Moore, asked if he would help write the text for the plaques. Mowbray made sure his portraits were truly holistic, capturing scientific accomplishments as well as achievements in fields such as music, politics and business. “The university can claim to have turned out people who’ve been able to apply the lessons they learned in engineering in many other ways,” says Mowbray.

It’s important for Mowbray to show students not just what the engineers have done, but their path to success, using colourful and compelling language. He writes that Murray Willer’s career was, like many engineers of his age, “hardened by the fires of the Second World War.”

“These are development stories,” says Mowbray, that show “how the engineer develops from his or her early days into a highly productive member of society. How they got there is an important part of the story.”

Mowbray’s father graduated from U of T in 1915, and some of his children and grandchildren are graduates as well. Involvement with family is but one of many ways the 82-year-old stays active. “I do this work, about a day on each award, to make a grateful contribution to the university,” he says, adding that a favourite quote from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow sums up why he does it: “Lives of great men all remind us/We can make our lives sublime/and, departing, leave behind us/Footprints on the sands of time.”

Bonnie Stern and Raymond Rupert

How’s this for kismet? Bonnie Stern (BA 1969 New College) and Raymond Rupert (MD 1972, MBA 1985) first met at the age of nine at an Ontario summer resort, where they put on a play together. “I was on props,” smiles Rupert, “and she was this bossy little lady.” That seemed to be the end of it, even though the two were contemporaries at New College in the late 1960s. They weren’t reunited until 1978, when Rupert – by this time a successful doctor – wanted to learn how to cook. He enrolled in one of Stern’s highly regarded classes; the two have now been married for 25 years.

Stern will tell you that she was hardly bossy while at New College. “I was so quiet that one time I asked a question in a tutorial and everybody clapped,” she says. She planned to be a librarian, but a postgraduate stint studying cooking put an end to that idea: she is now one of Canada’s most celebrated cookbook authors, and owner of the prestigious Toronto culinary school that bears her name.

Her community work has been similarly impressive, and includes fundraising for New College and sitting on the University of Toronto Alumni Association’s board of directors. When Stern heard about U of T’s Alumni Mentorship Program, she knew it would be the perfect way for her husband to mark his own return to the university.

In addition to his medical degree, Rupert holds an MBA from the Joseph L. Rotman School of Management. He is both a family doctor and “case manager,” acting as a go-between for patients with complex medical problems, who often find themselves caught in a confusing labyrinth of experts. Under his tutelage, students learn lessons in management as well as medicine. “Students come and act as my shadow,” says Rupert. “I’ll give them a challenge and let them work it out.” This way, students can see what medicine or management is like before they commit to entering it.

Food plays a central role in the couple’s U of T involvement. Rupert likes to create a relaxed atmosphere for his mentees, planning initial meetings over dim sum in an uptown restaurant, sometimes with the couple’s three grown children in tow. And for a recent fundraiser at New College, Stern put on a “food trends presentation,” showcasing the evolution of the food scene in Toronto from the time of her graduation (“there were barely any restaurants then”) to the multicultural gastronomy of today. There are other food-centred plans, one of which may see new students invited to the Stern/Rupert house for a home-cooked meal. The kitchen is also an area where Rupert is called on to participate. “I chop and peel,” he says. “But she’s the star.”

William Ostrander

“I’ve never left!” exclaims Bill Ostrander (BA 1972 Victoria, MA 1978, LLB 1980), looking back on many years of study at – and tireless service to – the University of Toronto. Ostrander completed his undergraduate, master’s and law degrees here. Now, he’s being recognized as a pivotal figure in the development of the new Mark S. Bonham Centre for Sexual Diversity Studies at University College.

Established in 1998, the Sexual Diversity Studies (SDS) program offers undergraduate courses, hosts academic and community events, and promotes research into sexuality. Its activities will now accelerate thanks to a million-dollar donation from Bonham, the president and CEO of Stoney Ridge Estate Winery. Bonham, who attended University College, previously worked with Ostrander on Toronto’s Inside Out Gay and Lesbian Film and Video Festival, and served on the SDS advisory committee (of which Ostrander is now chair). Bonham’s donation will help the program with initiatives such as a graduate program and a regular academic conference.

A resource like this hardly seemed possible in the early 1970s, when Ostrander was a student at Victoria College. He was involved in many activities at school, but suffered from feelings of isolation. “I was completely closeted,” he says. “I did not know any other gay people. It severely affected my academic performance, and I had long periods of depression where I was unable to complete any academic work at all.”

Today, however, things are different – certainly at the university level. “There’s still homophobia in our society, but it’s not very prevalent anymore at U of T,” notes Ostrander, 56. “People in senior levels of administration clearly see the program as an important thing to do. Many of them have stepped up and helped, and it does U of T credit.”

It’s easy to see how the charming Ostrander (who practised corporate law for 22 years and is now in private business) has been able to drum up so much support for the centre. “I’m always meeting new friends,” he says. “I really like people.”

Susan Eng

Not many tax lawyers have parallel careers as social activists. But more than 20 years in business have given Susan Eng a tough, practical perspective – one she’s been happy to apply to her impressive range of community activities.

Now in her seventh year as an alumni governor on Governing Council, Eng’s watchword is accountability. “For me, this means that you look at an institution’s values. Then you look to see whether or not it has the best programs to achieve them. It’s not good enough for a committee just to say, ‘we’re on it.’ We need to account for how the university services its own values.”

For Eng, these values include diversity and student mentorship. As a governor, she also works to ensure that the university provides adequate funding for student aid, to increase accessibility for all deserving students. U of T has changed radically since the days when Eng, the child of Chinese immigrants, used to walk from her home at the corner of Howland Avenue and Bloor Street to attend classes at University College in the early 1970s. “There was a lot of cliquism then, and very few resources for visible minorities,” she says. Diversity and tolerance have certainly increased since then, but Eng warns against complacency. “These values have to keep being rearticulated, to each new generation of politicians and students.”

Alumni engagement is also significant to her. “Fundraising is the primary culture, but people get tired of being asked for money without a reason why. We need not only alumni money, but alumni input.” Eng believes that doing “good” doesn’t always mean doing “nice.” On the other hand, she’s learned what brings results and what doesn’t. She’s not big, for example, on protest rallies or in-your-face tactics. “You have to appeal to people’s self-interest,” she says, pointing to another of her recent accomplishments: acting as co-chair of the coalition that ultimately secured redress and a Parliamentary apology from the federal government for immigrants who were forced to pay the notorious Chinese Head Tax.

Eng is best known to Torontonians as the former chair of Toronto’s fractious Police Services Board, a post she held in the early 1990s. This “trial by ordeal,” as she describes it, was where her biggest lessons in accountability were learned. “It was a fascinating time,” she says now, the public nature of which “forced me to do my job better than I’d ever done before.”