Soon after Harold Heft was diagnosed with an aggressive brain cancer, he started searching for a book that might offer some comfort or wisdom as he confronted a frightening, uncertain future. A voracious reader and professional writer, he was looking for true stories about how people bear what feels unbearable. He couldn’t find these stories collected in one book, so he decided to create one himself.

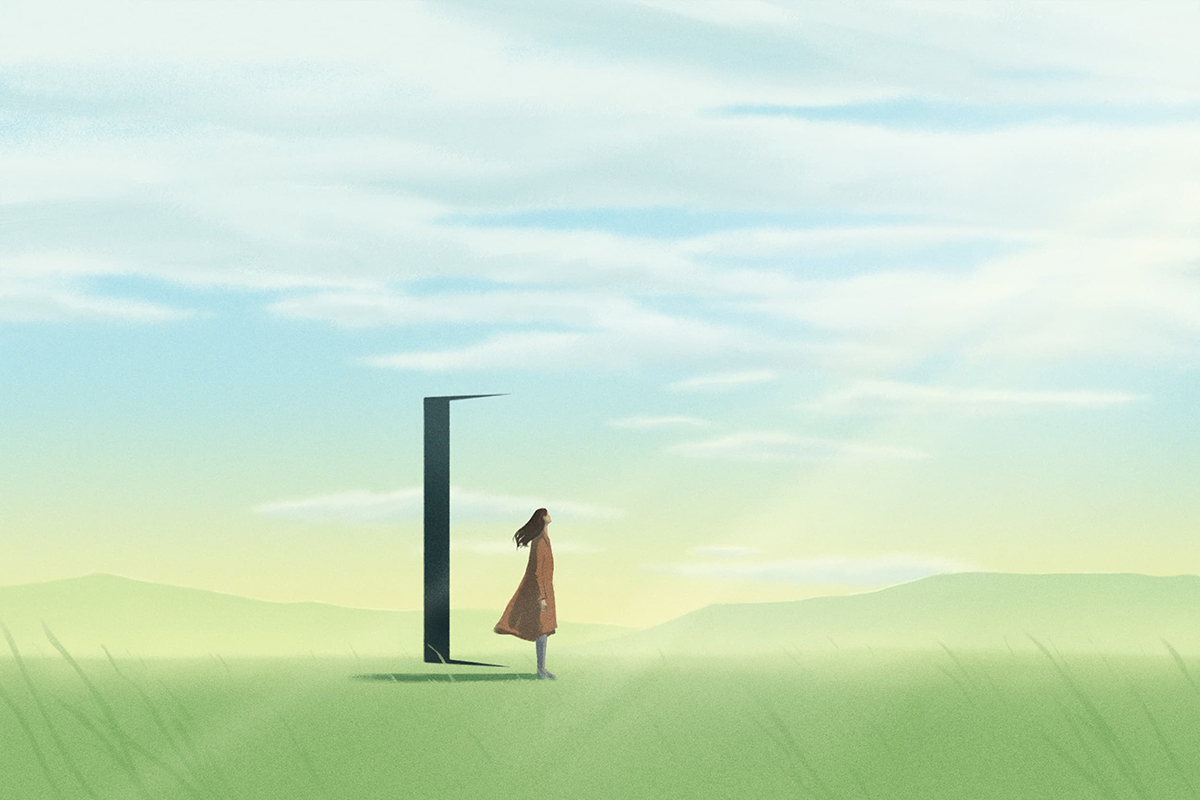

A Perfect Offering: Personal Stories of Trauma and Transformation was published in late 2020, more than five years after Heft’s death in 2015. The book was incomplete when he died, so his wife Suzanne Heft (BA 1990 St. Michael’s) and longtime friend Peter O’Brien worked together to finish it. “Harold envisaged a book that would help readers feel less alone with their trauma, whatever it was, by catching a glimpse of their own suffering in the suffering of others,” says Suzanne, who met Harold when they were both working at U of T in the 1990s. “At the same time, he thought it could offer a way of understanding how people often find meaning and hope, despite their anguish and pain.”

The book has 31 stories of trauma – from sexual assault and the legacy of residential schools to chronic illness and the loss of a child – by award-winning writers and first-time authors alike. They form a kaleidoscope of pain, but also sparkle with resilience and recovery. “It’s not an easy book, but I find a great deal of hope in its pages,” says Suzanne. “These people didn’t give up. They chose to affirm life in the face of what seems like abject destruction.”

It took a long time for Janelle A. Girard (BEd 2008 OISE) to feel ready to publicly share her experience of being drugged, abducted and sexually assaulted in 2009. But the chance to be part of A Perfect Offering came at the right moment. “I immediately had this overwhelming excitement about finally telling my story,” she says.

Girard, who was also seriously injured in a car accident a few years after the assault, knows the harmful effects of trauma all too well. But she has also seen its unexpected gifts. “This book is important because it destigmatizes trauma and focuses on transformation,” she says. “Just look at where the authors are now. We persevered and came out the other side to tell our stories.”

One of Girard’s biggest transformations has been to become a writer. She got involved in A Perfect Offering after Suzanne contacted her teacher at U of T’s School of Continuing Studies’ creative writing program looking for submissions. That teacher was Marina Nemat, the bestselling author of Prisoner of Tehran – a memoir of her arrest, imprisonment and torture after the Islamic Revolution of 1979. Nemat is also among the book’s contributors, with a story about reuniting with a high school friend who was in the same prison at the same time as her 35 years before.

Nemat says most of the students who have taken her memoir-writing class over the past eight years are there to write about a traumatic event. Another two of Nemat’s students are included in A Perfect Offering: Janet Culliton, whose story is about having a daughter with autism prone to violent episodes, and Jennifer Boyle (PhD 1999), who writes about losing a lifetime’s worth of memories to profound amnesia. “These stories give us strength and hope,” says Nemat. “We cannot put trauma on a scale and measure it, so comparing suffering is irrelevant. What we need is to learn from one another and know that we are in good, wise company.”

Harold began assembling that wise company before he died, but he didn’t get to read many of their finished stories. He had received about a third of the submissions when he became too sick to work on the book. Though he opted for all available medical treatment, he died a year and a half after collapsing at work one day in 2014. He was 49 when doctors discovered he’d had a seizure caused by a brain cancer called glioblastoma.

After he recovered from the seizure, his speech came back quickly. His ability to read and write, however, rapidly deteriorated then permanently disappeared. For a lifelong reader and writer with a PhD in literature, this was a devastating loss, says Suzanne. “Before, he wrote all the time. He always had a notebook within reach.” As he built his career in fundraising and communications at U of T, the Hospital for Sick Children and other non-profits, he always made time to write outside of work, publishing two books and many poems, articles and reviews.

“When he realized that his old life was never going to come back, he had to decide how to use his remaining time,” says Suzanne. “The book is an expression of how he integrated his former self and his new reality.” After Harold came up with the idea of A Perfect Offering, Suzanne acted as his scribe, sending emails to potential contributors and taking notes for his own story. “If he felt in the mood and had the energy, he would say, ‘Open the laptop.’ It gave him a sense of purpose and meaning.”

Several months after his death, Suzanne returned to the project with Peter O’Brien, who had worked with the couple at U of T. (In O’Brien’s contribution to the book, he recounts his father dying when he was a toddler, leaving his mother to raise 10 children.) “Peter helped Harold get the idea off the ground, then helped me solicit, edit and sort the submissions into a final manuscript,” says Suzanne. “I was determined to keep going. Now it gave me a purpose. It was a way of collaborating with Harold, even though he wasn’t there anymore. My only concern was whether to publish his unfinished story. He would have wanted to revise it countless times.” She decided to include it, explaining that its imperfection aligns with the sentiment in the book’s title, inspired by Leonard Cohen’s song “Anthem,” where he writes: “Forget your perfect offering / There is a crack / A crack in everything / That’s how the light gets in.”

In Harold’s story, “The World I Once Inhabited: Draft One,” he describes grappling with questions he rarely considered before his diagnosis. For example, how should he live with the sudden awareness that death could come at any time? And in what way is he the same person he always was? “Harold struggled with these issues until the end,” says Suzanne. “He didn’t have enough time to reckon with his experience of trauma. But his book brought together people who did.”

It’s happenstance that the book was released during a global pandemic, yet Suzanne hopes it may speak to those coping with the innumerable traumas of the past year. “While the book is an expression of the writers’ courage, it’s also turned out to be a book for this moment,” she says. “Anyone should be able to pick it up and feel the power of the bravery of everyone in it. Maybe, then, they’ll be reminded that there’s a tiny seed of that bravery in them too.”

Recent Posts

People Worry That AI Will Replace Workers. But It Could Make Some More Productive

These scholars say artificial intelligence could help reduce income inequality

A Sentinel for Global Health

AI is promising a better – and faster – way to monitor the world for emerging medical threats

The Age of Deception

AI is generating a disinformation arms race. The window to stop it may be closing