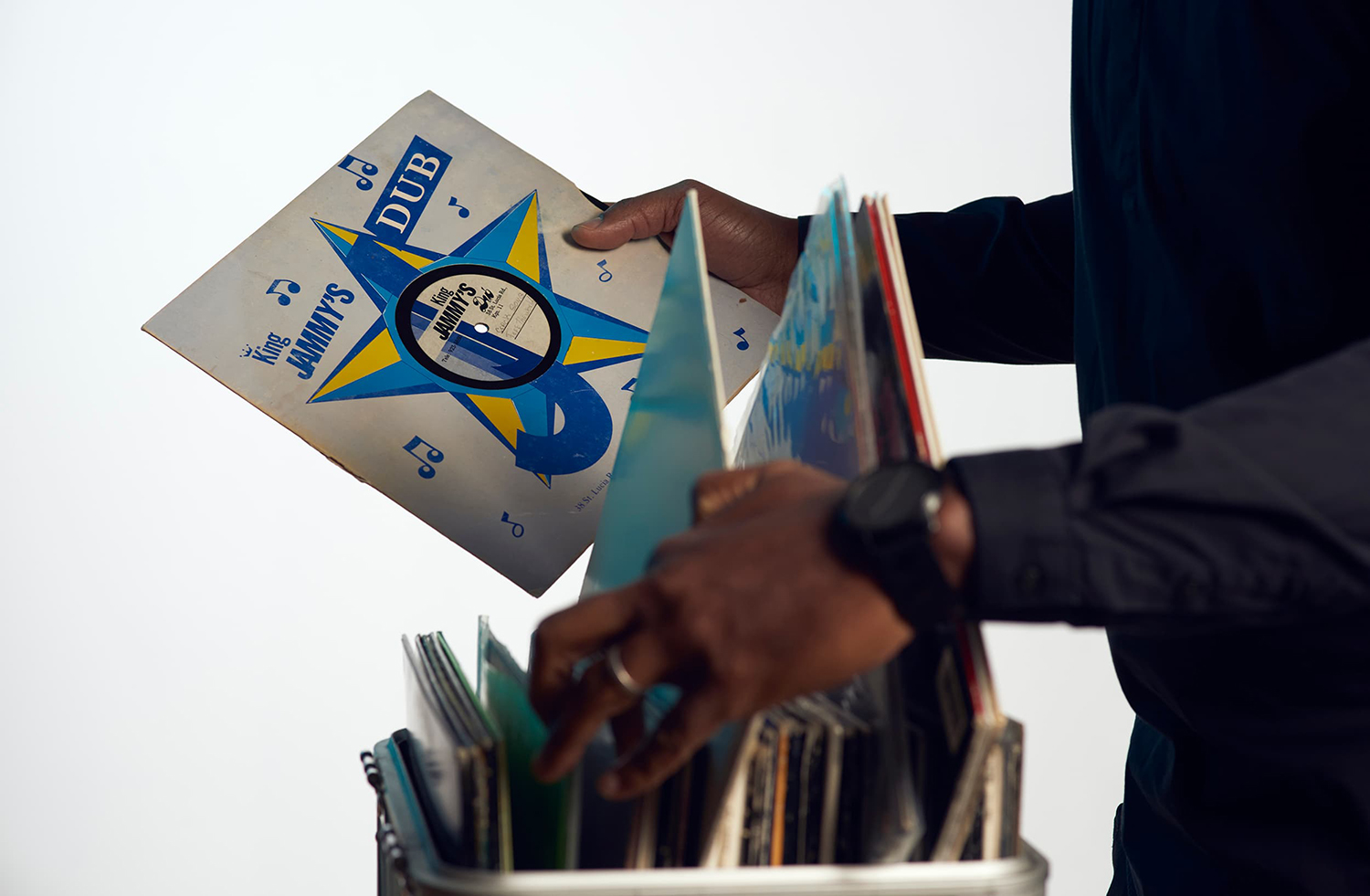

There’s a special section in the basement of Mark V. Campbell’s house where he keeps his records. He estimates there are thousands of them – mostly hip hop.

The collection spans decades and includes recordings by many of the genre’s trailblazers in Canada. Campbell, an assistant professor and associate chair in the department of arts, culture and media at U of T Scarborough, continues to use the records not only to DJ and sample tracks for his own music, but also to chart hip hop’s evolution in Toronto. The records contain a trove of information – unreleased remixes, little known B-sides, as well as the name and locations of defunct record companies and recording studios across the city.

“It’s like a breadcrumb trail showing where hip hop was being made and by whom during its early days in Toronto,” he says.

For more than a decade, Campbell, who is a DJ, curator and scholar, has been a mainstay in the efforts to preserve the history of Canadian hip hop. In 1997, he co-founded and ran the Bigger Than Hip Hop radio show, which aired for 17 years on Toronto’s CHRY-FM. And in 2010, he helped establish the Northside Hip Hop Archive – an ongoing project to digitize and archive Canada’s hip-hop music and culture.

It’s an unlikely career path for a kid who grew up in Scarborough, Ontario, and never imagined that a career involving hip hop was possible. In the 1980s, Campbell says positive representations of Black people in the media were rare, and Black history and culture were often overlooked in schools. Hip hop became a way for Black people to learn their own history, to point out racism in politics and society, and to discover how the media distorted the reality of Black lives.

“Something like Public Enemy’s ‘Shut ‘Em Down’ was one of the first songs I remember as a kid,” says Campbell. The song was about boycotting Nike and about the need for corporations to meet their responsibilities in Black communities. “That’s a lot for a 13-year-old to take in. I was learning about the world through hip hop.”

Looking back now as an academic who studies the genre, Campbell believes several elements made hip hop so magnetic to the masses, especially to youth.

Despite the focus on fashion, early hip hop wasn’t about showing off expensive taste, says Campbell; it was more about having the confidence to be different – to put your hat on backwards or to wear bold colours. The music took risks, too. In no other genre were artists sampling small portions of old recordings to make new ones. The artists were also multidiscliplinary; they embraced other aspects of hip hop culture, such as breakdancing, graffiti and DJing – all of which had originated in the streets.

Hip-hop artists engaged with – and were critical of – each other in ways that didn’t happen in other genres, says Campbell. They called each other out for a lack of originality, for copying another artist’s style, or for a perceived lack of skill. “The importance of representing the culture the right way – of authenticity – stems from how the entertainment industry has profited off of Black culture and misrepresented Black life since the days of minstrel shows,” he explains.

Hip hop also attracted audiences for its critique of American society. With their hit track “The Message,” for instance, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five gave a first-person account of inner-city poverty in New York in the 1970s. At a time when the city was suffering from crippling debt and high unemployment, artists in marginalized communities were offering ethnographic accounts of what life was like for those who were suffering the most, says Campbell.

Canada’s own hip-hop scene developed in the mid-1980s, in Montreal and Toronto, and differed from America’s both musically and culturally. Toronto hip hop uniquely celebrated the Caribbean identity of Canadian artists. Campbell highlights a freestyle (improvisational rap) battle between local favourite Michie Mee and New York MC Sugar Love. “Michie Mee was outperforming Sugar Love, but then she started rhyming in patois and the crowd just lost it. The American artist couldn’t compete.” Other Toronto artists such as Dream Warriors and Kardinal Offishall also relied on a Caribbean esthetic in a way their American counterparts did not; their music became a way to celebrate their heritage, Campbell says.

When Canadian hip hop contained a social message, it was sometimes delivered in a Canadian context. Campbell points to “Nothing At All,” a 1991 song by Maestro Fresh Wes that challenged idealistic Canadian narratives about multiculturism and criticized Thanksgiving as a colonial holiday.

Campbell, who got involved in Toronto’s hip hop scene in the early 1990s by going to shows and DJing at small parties, was working as a high-school supply teacher in the late 2000s when he came up with the idea for a hip-hop archive. He had been planning to teach his students about local hip-hop history, but much of that history, from the early 1980s to early 2000s, wasn’t documented online. “I realized that much of what we had done had not made it to the internet, and there was no way to convince my students that Canada had a thriving hip-hop community,” he says.

The archive that Campbell then started has grown significantly over the past decade. It now includes artifacts such as show posters, flyers, photographs, oral histories, audio recordings, press clippings, and even high school lesson plans on hip-hop history.

Campbell, who holds a fellowship at U of T’s Jackman Humanities Institute, notes a deep connection between his long-standing interest in digital archives and his current teaching and research at U of T Scarborough: both aim to “decolonize” knowledge about Black culture. (Decolonizing knowledge is a term commonly used in cultural studies to challenge the idea that Western knowledge is “universal.”) Campbell says he uses the concept in his own work to address the gaps that exist in our understanding of Black culture, and to ensure that the creation of knowledge about Black culture does not reproduce existing stereotypes. He wants to help create knowledge that counters existing narratives about Black culture as “unmodern” or “lacking.” And he draws on the musical and cultural innovations of hip hop as examples.

From his undergraduate and graduate courses on DJ and remix cultures, Campbell hopes his students come to see the subversive nature of these musical innovations and how they have nourished Black life. “It all started with recycling records,” he says. “Some argued, and continue to argue, that sampling isn’t real music. But I find it inspiring that a group of racialized artists found a way to generate cultural value. You just had to be creative,” he says.

Campbell says it is remarkable that hip hop has become so influential in the development of Western popular culture – in spite of being an art form rooted in the Black experience outside the mainstream and inspired by the outright neglect of Black communities. “I want to dedicate my life to exploring and amplifying the creative and artistic genius embedded in Black life, with hip hop being one example,” he says.

“I thought, and continue to think, that if we explore the many creative ways Black life has flourished, we might arrive at new understandings of contemporary society.”

Five Must-Hear Canadian Hip-Hop Tracks

As selected by U of T Scarborough professor Mark V. Campbell

“Jamaican Funk-Canadian Style” (1990), Michie Mee, with DJ L.A. Luv

Michie Mee straddles reggae and hip-hop, capturing the visual esthetics of Jamaica’s dancehall culture while also situating herself in Canada. A contemporary of Queen Latifah, Mee’s strong womynist leanings and lyrics show how some women in hip-hop chose to represent themselves outside of the institutions that sought to objectify them.

“Wash Your Face in My Sink” (1990), Dream Warriors

The sample of Count Basie’s “Hang on Sloopy” brought a refreshingly jazzy feel to hip-hop culture. This Juno Award-winning group also proved that some kids from Toronto’s much-maligned Jane and Finch neighbourhood could sell out stages abroad. The international success of Dream Warriors opened the door to a new generation of Canadian hip-hop artists.

“Dreaded Fist” (1997), Rascalz

A haunting vocal sample makes this track a memorable debut. Vancouver-based Rascalz were one of the few 1990s groups to continue to include dancers and a DJ in their line-up, much like 1980s artists Big Daddy Kane and Heavy D & the Boyz.

https://youtu.be/nvCleNb1vB4

“Feeling Reserved” (2000), Warparty

Warparty cleverly represented the plight of Indigenous communities in a way that highlighted their lyrical dexterity. This trio of emcees presented a sharp ethnographic analysis of the residues of colonialism that continue to haunt Canada and disrupt the lives and livelihoods of its First Peoples.

“Africville” (2007), Black Union ft. Maestro Fresh Wes

Hip-hop’s deep respect for local neighbourhoods has resonated since Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five released “The Message” in 1982. Here, Halifax’s Black Union and Toronto’s Maestro Fresh Wes provide a history lesson on the forced relocation of residents of Africville – a long-established Black Canadian settlement that Halifax’s city council ordered demolished in 1964.

Five Key Moments in Canadian Hip-Hop History

February 1984

Montreal’s first Break Dance Battle draws a sold-out crowd at the Spectrum concert hall.

March 1986 & 1987

Two freestyle rap battles pit Toronto artists against their New York counterparts.

August 1989

Rap City first airs on MuchMusic, with host Michael Williams. The weekly 30-minute show is the first in Canada to play hip-hop videos to a national audience.

July 1995

The Concrete Canvas graffiti festival is founded by artist Leon ‘Eklipz’ Robinson in Hamilton, Ontario.

March 1998

Vancouver hip-hop group Rascalz refuse to accept their Juno Award to protest the omission of the hip-hop category from the main ceremony.

Recent Posts

People Worry That AI Will Replace Workers. But It Could Make Some More Productive

These scholars say artificial intelligence could help reduce income inequality

A Sentinel for Global Health

AI is promising a better – and faster – way to monitor the world for emerging medical threats

The Age of Deception

AI is generating a disinformation arms race. The window to stop it may be closing

One Response to “ Charting Hip Hop’s Course ”

I'd like to mention the Main Source. They were Canadian DJs/producers along with L Pro (USA). They gave us Nas.