Ever since the ancient Mayans first used sea shells as dentures, scientists have worked hard to identify which substances can be safely introduced within the body to repair, replace or even create body parts. Hence the fascinating field of biomaterials: one that has given rise to everything from heart pacemakers to contact lenses to modern day tissue engineering.

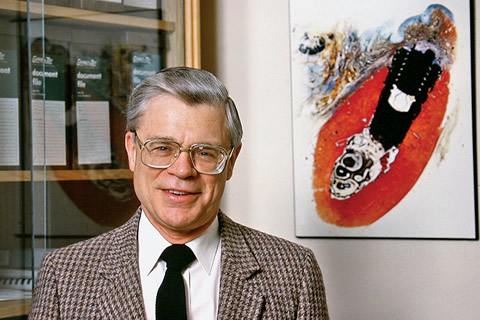

Dennis Smith is recognized as a major figure in this ever-changing domain. The U.K.-born chemist, who passed away in February at the age of 85, came to Canada in 1969 and eventually attained the position of Professor Emeritus at the Faculty of Dentistry. Smith first achieved renown for his contributions to hip replacement surgery. While working at a dental hospital in Manchester, he devised the idea of using dental acrylic cement to fuse an artificial hip with a human femur. The idea worked, and is still in use today.

This mix of chemistry, medicine and dentistry was unlikely at the time – but Smith’s particular brilliance lay in bringing these worlds together. “He was a communicator,” says Robert Pilliar, an engineer who was encouraged to work at U of T by Smith. “One of his great strengths was that he was very sociable, and able to reach out to anyone who might make a contribution.” In 1971, two years after his arrival in Canada, Smith gathered talents from four disciplines to found the Canadian Biomaterials Society, the first of its kind in North America. He later established the Centre for Biomaterials at U of T, where researchers have since produced a stream of innovations extending to almost every aspect of human health. The centre later merged with the Institute of Biomedical Engineering to form the Institute of Biomaterials and Biomedical Engineering.

After Smith’s retirement from the university in 1993, he became involved in what was perhaps the most heavily publicized biomaterials story in history – investigating the safety of silicone breast implants. A physical chemist, he had particular expertise on the reactivity of inert materials with living systems. Yet, it is worth noting that the implant crisis came at the dawn of great transition in his field. Around this time, “scientists started thinking not just of whether or not inert materials would harm the body, but whether they could actually contribute to cellular activity,” says Pilliar. Thus it is that Smith’s successors now use synthetic materials as scaffolding for living cells, from which they can actually grow new body parts.

The IBBME today includes professionals from three partner faculties, all working together to create a brave new world of biomedical advancement. Forty-five years ago, says Pilliar, “the university wasn’t tuned into the fact that we could create this level of activity between disciplines and faculties. That they eventually did was certainly very much Dr. Smith’s doing.”

Recent Posts

People Worry That AI Will Replace Workers. But It Could Make Some More Productive

These scholars say artificial intelligence could help reduce income inequality

A Sentinel for Global Health

AI is promising a better – and faster – way to monitor the world for emerging medical threats

The Age of Deception

AI is generating a disinformation arms race. The window to stop it may be closing

One Response to “ Dennis Smith Pioneered Biomaterials in Canada ”

Dennis Smith was one of my lecturers at Manchester University dental school in the U.K. He was a brilliant communicator and impressed on me the importance of questioning all we were told before accepting.