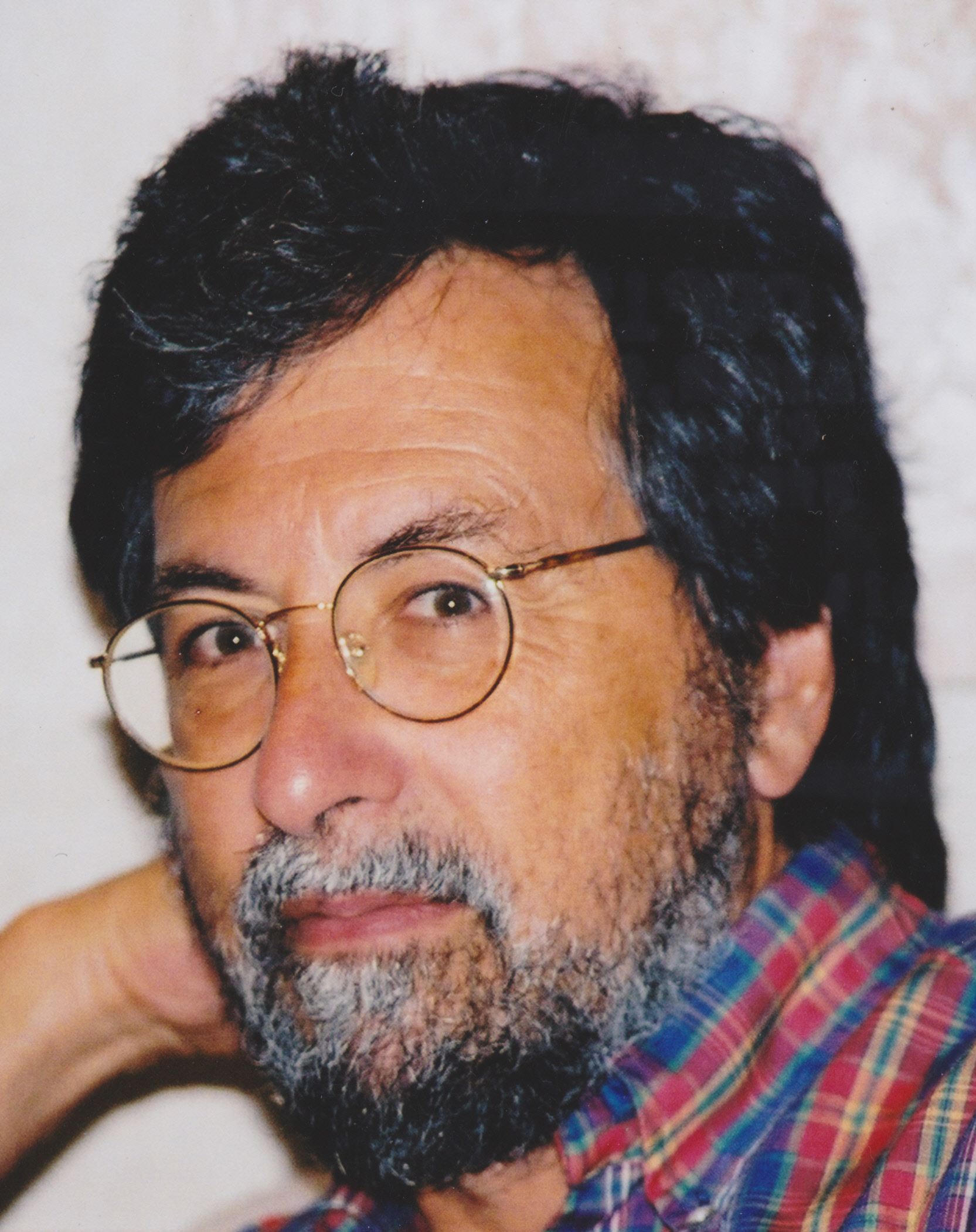

It was clear from early on that Robert Remis thrived on excitement. His work as a physician in the 1970s took him around the world – from remote Aboriginal communities in Canada to India, Burundi and Comoros. Ever restless, Remis would not settle down until he could find a health challenge to work on that was just as fascinating and complicated as he was.

In the human immunodeficiency virus, history gave him what he needed.

Remis, a Winnipeg native and long-time U of T prof who died of cancer on September 25, 2014, began to investigate HIV-AIDS in the epidemic’s earliest days. He obtained a master’s in public health from Harvard University in the early 1980s, and worked briefly for the U.S. Centers for Disease Control before moving to Montreal. There, he began to explore the spread of a strange and fatal new illness known as AIDS. He made it his life’s mission to track and prevent it as best he could, while becoming a top expert on how the virus that caused it was transmitted.

Colleague Dan Allman, co-director of the HIV Studies Unit of U of T’s Dalla Lana School of Public Health, says Remis’s lengthy experience as an epidemiologist ultimately made him an éminence grise at yearly AIDS conferences. By the time of his death at age 67, Remis “had seen more of the epidemic than most people; I mean, he really did see it all.”

In 1996, Remis accepted a faculty position at Dalla Lana. With funding from both the university and the Ontario government, he established and directed the Ontario HIV Epidemiologic Monitoring Unit, which would serve as a model for other provinces. In an effort to identify the presence of HIV in Ontario as painstakingly as possible, he designed numerous groundbreaking studies. Currently, “hundreds of children are born free of HIV infection because Dr. Remis advocated for prenatal HIV testing in Ontario,” wrote Dalla Lana dean Howard Hu on the occasion of Remis’s passing.

The tireless physician was, according to Allman, a stickler for precision. “He was challenging to work with, because his brain went so fast. You’d be on deadline, and he’d show up with yet another question. But it was only because he wanted to make the work better. He was so quick to grasp and argue concepts: a very frustrating colleague, yet one you couldn’t live without.”

Remis was a fierce advocate of traditional public health, says Allman. “Despite his enormous compassion, he was not willing to sacrifice public health for individual rights.” Remis was assailed by activists angry at what they perceived to be a core belief he held: that people with HIV who failed to disclose their status to sexual partners should face prosecution. While Remis “recognized the complexity of human nature, and the complexity of HIV disclosure,” Allman says, “he would hold fast to his beliefs, grounded as they were in a traditional public health approach. He felt that was his role. He was tough that way.”

HIV-AIDS was Robert Remis’s enemy, but also his passion: “because it presented such a conundrum, after so many years,” says Allman. “Also because of the complex role of stigma and discrimination within it. In his quest for social justice, that was something he thought important to address.”

The Fund in Public Health in Honour of Robert Remis will endow scholarships for U of T grad students researching ways to prevent infectious disease. Give at dlsph.utoronto.ca.