When Ayodele Odutayo was a first-year health sciences undergraduate, he figured he’d spend his summers working at a shop or restaurant. Then, his mentor – an upper-year student assigned through a scholarship program – suggested he apply for a hospital-based research job. Odutayo credits that tip for much of his later success.

“That first research job led to seven years of summer research positions at Sunnybrook,” says the 2013 Rhodes Scholar, who is taking a leave from his U of T residency in internal medicine to pursue a PhD in clinical medicine at the University of Oxford.

Odutayo, who was one of the few black students in his medical class at U of T, is trying to increase the number of black students who enrol in medical school. Black individuals make up less than one per cent of Canadian medical-school students, despite accounting for almost four per cent of the Canadian population aged 15 to 24.

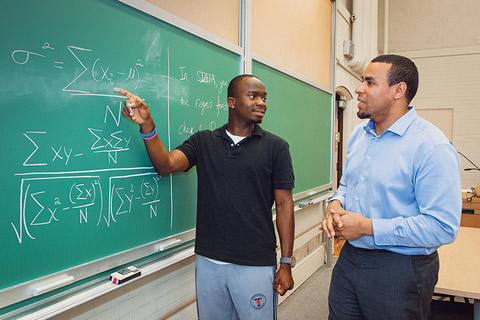

To bring about change, Odutayo approached Ike Okafor, senior officer, service learning and diversity outreach at the Faculty of Medicine. Odutayo suggested developing a non-credit biostatistics course for black undergraduates who want to apply to medical school. Not only would it provide practical research skills, it would also open up networking opportunities. In July, Odutayo and two other Rhodes Scholars – Connor Emdin and Peter Gill – taught the first three-week session to a class of five.

Projects like these are invaluable for students underrepresented in medicine, says Okafor. The course is part of a greater initiative he’s leading, called Community of Support. In collaboration with Undergraduate Medical Education’s enrolment services, the U of T Black Medical Students Association and the Black Physicians’ Association of Ontario, Okafor provides students with access to mentors, job-shadowing, volunteer and research opportunities, medical-school admission information and guidance.

Bringing more diversity into medical schools has been shown to enrich the learning environment and to increase access to care for patients from marginalized communities. And with the Community of Support serving almost 100 students across the province in just six months, there’s a big demand for this type of program.

Aquila Akingbade, like Odutayo, immigrated to Canada when he was 12. Currently a third-year undergraduate student, Akingbade plans to enter medical school and eventually become a neurosurgeon.

“It’s a bit intimidating because I feel like I have to compete against all these people who have so many connections,” he says. “No one in my family is a medical doctor or is in the medical field.” He’s motivated by the role models he met in the new biostatistics initiative.

“You have people who have similar experiences and can empathize with you,” he says. “And such successful people – Rhodes Scholars! You’re inspired, because you think ‘If these guys can do it, I can do it as well.’”

Recent Posts

People Worry That AI Will Replace Workers. But It Could Make Some More Productive

These scholars say artificial intelligence could help reduce income inequality

A Sentinel for Global Health

AI is promising a better – and faster – way to monitor the world for emerging medical threats

The Age of Deception

AI is generating a disinformation arms race. The window to stop it may be closing