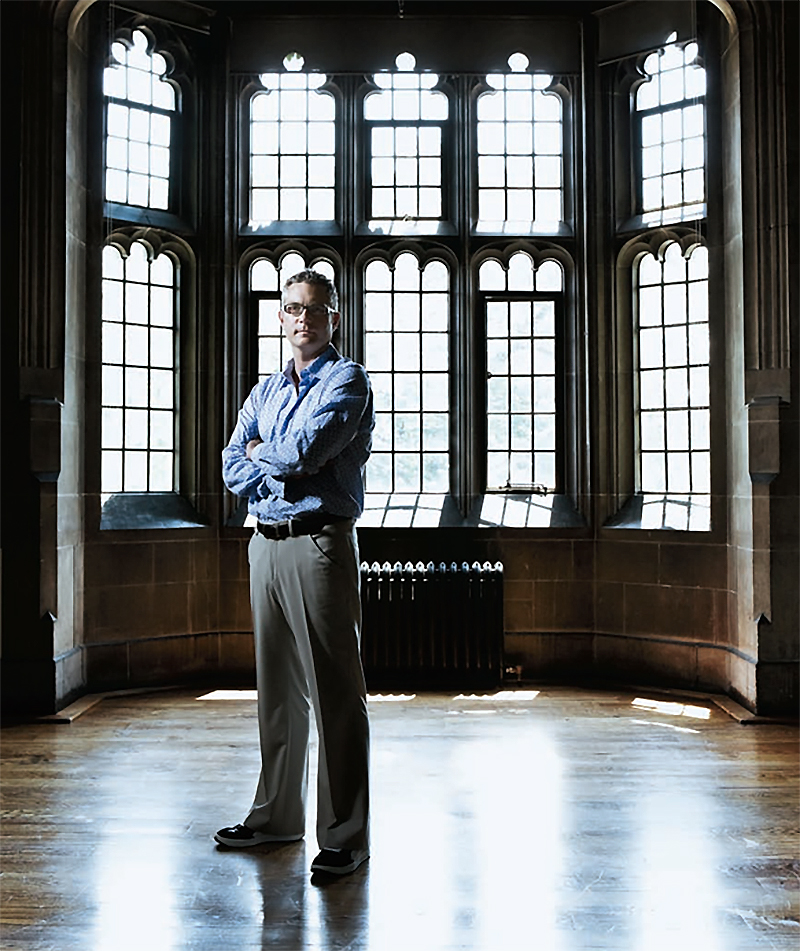

Following decades of bitter religious conflict in the Middle East among Muslims, Jews and Christians, few would imagine that the Judeo- Christian scriptures could have anything to do with Islamic thought. But the interconnections run deep, and can be traced back to medieval Arabic translations of the Bible, according to Walid Saleh, a professor of religious studies.

When Saleh was researching commentaries about the Qur’an some years ago, he stumbled across the writings of a 15th-century Islamic scholar who had become fascinated by a translation of the Bible into Arabic. The medieval scholar had befriended a rabbi who helped him understand the original Hebrew text. The scholar, in turn, wrote impassioned and controversial treatises on how the Bible could be used to interpret the Qur’an. “He considered it permissible for Muslims to draw on the Bible for religious purposes,” says Saleh, who published In Defense of the Bible, a translation of the scholar’s work, two years ago.

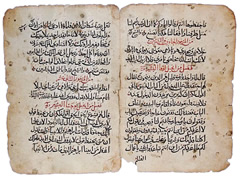

Since then, Saleh has embarked on a comprehensive study of the history of Arabic Bibles, the least well known among the broad range of translations of the sacred Judeo-Christian text. They were used by Arab-speaking Jews and Christians who lived in the Middle East in the medieval period.

Raised in Lebanon, Saleh, 44, studied at the American University in Beirut during the civil war and obtained his PhD from Yale. His fascination with Arabic-language Bibles actually dates all the way back to his doctoral work, but he couldn’t find a thesis supervisor because there were so few scholars who knew the field. “It’s an old interest that was sidelined,” he says.

To further advance his historical sleuthing, deciphering and commentary, Saleh has gone back to school to learn ancient and modern Hebrew, thanks to a Mellon Foundation fellowship.

One area of his research that Saleh finds especially intriguing: many 19th-century Arab novelists and poets were strongly influenced by these Biblical texts. As he explores the literary and liturgical interplay between the Bible and Arabic thought, Saleh has unearthed hitherto unknown intellectual and spiritual connections between these great cultures. As he observes, “This is a long and complicated story that’s not represented by our current political environment.”

No Responses to “ Islam and the Bible ”

The introduction to the Arabic transliteration of Maimonides, "The Guide for Perplexed" by the famous Turkish professor Hussein Atay, said that Jewish Studies could help Muslims understand Islam. At first, I found this difficult to grasp. But after two years at Hebrew College in Boston studying for a master's degree in Jewish Studies, I came to understand Prof. Atay's opinion. There are many Koranic terms and concepts that Muslim interpreters couldn't explain because they are Hebrew.