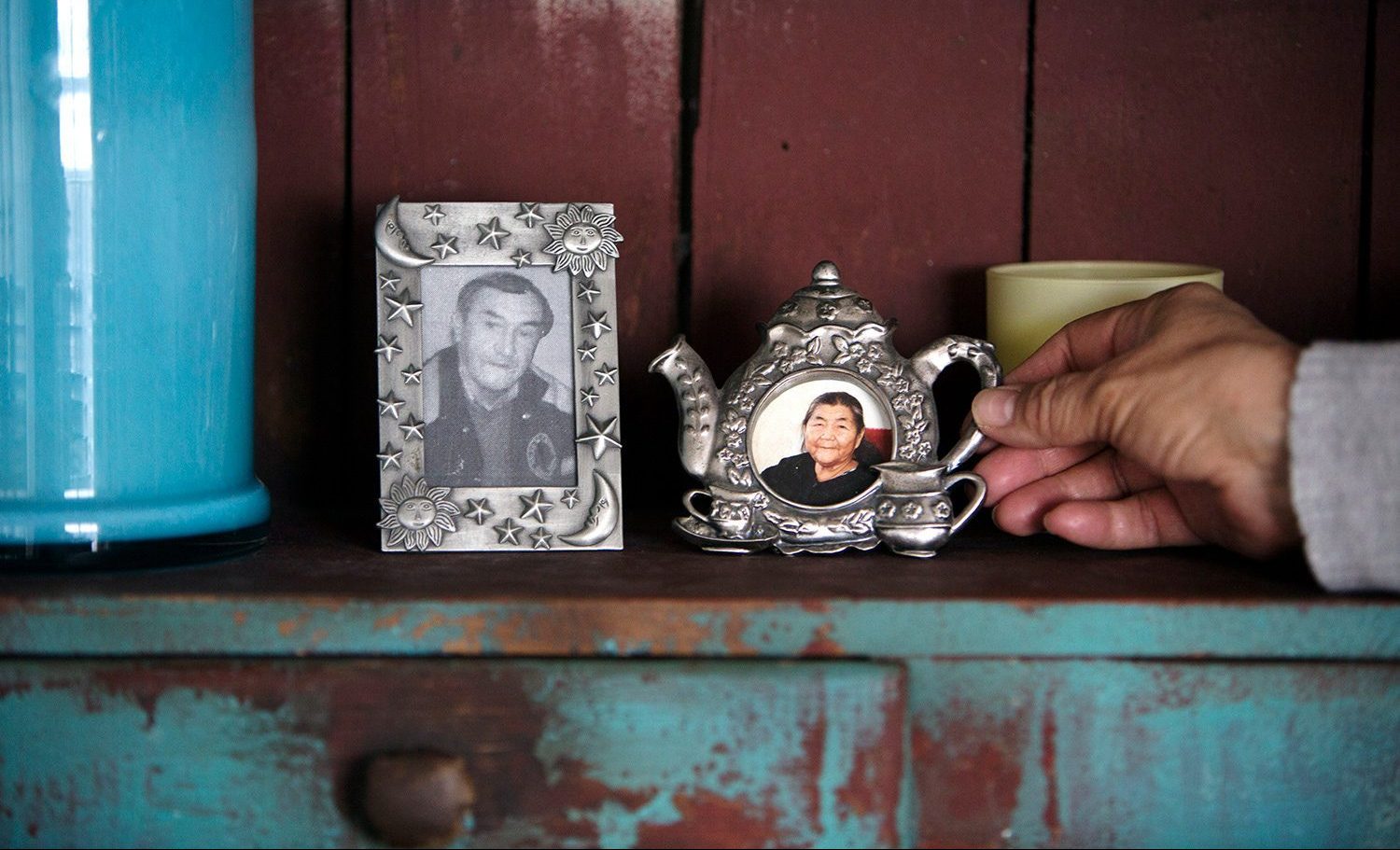

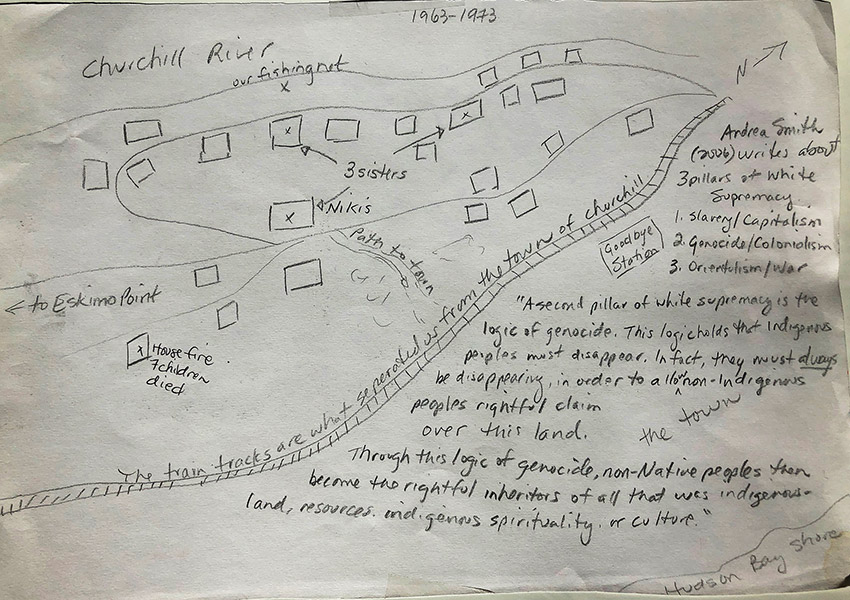

Brenda Wastasecoot is the youngest of 11 children born to Maria and Harold Wastasecoot in the Flats, an Indigenous village near Churchill, Manitoba. She did not attend a residential school, but she witnessed the changes in her siblings, who all did, when they returned home every summer. Her stories from the past show, with art and memory maps, what happened in a Cree girl’s home in the 1960s when Canada’s Indian education policies intentionally fractured Indigenous families and communities. This article is adapted from her U of T doctoral thesis.

Only two of my siblings have told me bits and pieces of what their life was like at residential school. The school officials would not allow my sister to attend my late brother Horace’s funeral. She cried about this once. She said they told her, “You didn’t know him well enough.” They had attended the Mackay School in Dauphin, Manitoba. My brother Walter told me he often felt he had to protect our younger brother, Frank. The weight of this responsibility for his baby brother affected him right up to the day of Frank’s death three years ago, and still does.

Early in my career, I taught a course at Assiniboine Community College in Brandon, Manitoba. The Brandon Indian Residential School, located on the north hill of the city, had been torn down; it rested in a pile of rubble. I went to these ruins on several occasions – once with a group of students from the course. At that time, I took a small piece of concrete and did a sharing circle with them as a way to open up this part of our shared past as Indigenous and non-Indigenous people and to begin voicing our thoughts and feelings about the history of residential schools. At the end of that course, the students and I returned to the site, where they placed offerings for the spirits of the children buried there: homemade bread, jam and a wooden plaque engraved with words of love. Each of the students spoke as they presented their gift as a way to honour those children left there, whose spirits still linger near that place. We said a prayer together and walked away.

There are not enough words to express the emotions felt when all of your sisters and brothers are survivors of these institutions. There are no words – only bits and pieces of pain. I went to the ruins with a purpose. In looking back at my history and trying to understand what happened to my family, I walked and climbed the massive pile of rubble with hopes of finding some answers to my question: How does this connect to my own story?

On one visit to the leftover heap of the Brandon school, I found a steel door. It called to me, “Try opening this door!” I photographed it. My daughter and I tried to lift it. It was too heavy. I had hoped we could stand it up so I could see how tall it was. Would it tower over a child’s head? Could a small hand open this steel door?

Once back to the house I showed the photos to my niece and her husband. They both said, “Let’s go get it!” My niece, who is an artist, wanted to see what she could do with it as an installation piece. The feeling of excitement overtook us; we got into the truck and sped to the old residential school site. The sky began to darken; clouds started to gather and move in the direction of the steel door. We had to hurry to avoid the storm. As we got closer to the site, the wind gained momentum, as if it too wanted to lift the door for us, and open its hidden secrets. To the rest of Canada, it may be a piece of rubble – a piece of history thrown away and forgotten – but to us, it was a way in.

The thought of whether it would still be there did come to me, but then I wondered, who would take it? Who would be interested in a door that was more than 120 years old? Only an artist would want it – an artist who would never forget the suffering of generations of her people. I climbed back up the heap of history and led my niece and her husband to the door. We all stood around it for a moment, looking at it as if it would start speaking right there on the spot, telling us what so many children have gone to their graves not saying. But no, it would not speak so readily. It would need to be studied for many years to come by scholars like me.

We each grabbed a corner trying to lift it from its place; it would not be taken easily. My niece’s husband grabbed the door handle and raised it up a few inches, enough to drag it toward the vehicle. I took a hold of the other side of the door handle. My niece pulled it along. Just then I could feel the raindrops hit my face, my hands; tears began to roll down from the sky. We got the steel door and all together lifted it into the back of the truck, securing it down for the drive back into town.

Why was this door so important to me? I talk about the finding of this steel door because it illustrates how my family continues to struggle with the past. It shows how I have tried to grasp their residential school experience so that I could begin to understand what happened to my brothers and sisters.

When I began looking back at this time in my past, I received a dream about a white man sneaking children out of my house. In the dream, I am a child, standing in a darkened room, in a house from long ago. In the darkened room, I can see there are people passed out on the floor. As I try to reach the door to get out, one man on the floor tries to grab my leg. Quickly I jump back, out of his reach. I try to escape again, and the same thing happens. I become overwhelmed with fear and feeling vulnerable and unsure how to get around him. I imagine the inevitable will happen once again – rape, that is. Then a white man appears and he is holding a small child in one arm. I think she is his daughter. Very quickly, he steps across all the bodies with such excellent footing and precise timing that he is able to traverse safely to the door without waking anyone. I am aware that the people on the floor are hurt and would not be there otherwise, so with a sense of compassion, but also a feeling of dread, I try my best again to get across to the door safely, but again the drunken man tries to grab me. I ask the white man to take me on one of his feet, and he does while holding the other child. On his foot, I am able to get across to the door and then out of the house. That is how I escaped this situation.

As I often do, I wonder what message is in this dream. I wonder for the years that follow. Then it finally comes to me; the dream is about the white man stealing the children from those who have become incapacitated. My parents became incapacitated by alcohol. This became their strategy of escaping an impossible situation. It could have been why they were not at the train station when my siblings were leaving for residential school; they were in the bar again. With Canada’s laws in place to uphold the assimilation policies, parents were powerless to rescue their children.

The nightmare also alludes to my feeling overwhelmed and trapped. As an Indigenous scholar, I often feel like I have no supporting arguments. I need the assistance of the more learned or advanced researchers of this vast industrial complex called Education. Scholar Kathleen Absolon very cleverly provides this “leg to stand on” in her petals of methodology. She writes: “Enacting re-search that is of Indigenous ways means that Indigenous re-searchers work to advance Indigenous perspectives, world-views and methods in all areas of education, searching and scholarship.” This is why I have chosen to do autoethnography; I want to add my Indigenous perspective, so that others who may follow can have a “companion” as they write their life story.

An Elder thought this dream was about how I had to navigate through trauma. Traversing trauma is about finding a clear path out, placing your feet carefully to not create more damage, but to free oneself from the wreckage. As a child, I did not understand the difficult situation my siblings were placed in. I think about my siblings and how they had to leave me there in a community devastated by alcoholism and violence. I realize now that it was never their choice to leave me there. Families were torn apart. My brothers and sisters had to leave their baby sister, their parents, their cousins, aunts and uncles. To this day, we have not spoken about this time. If I could, I would tell them that it was not their fault. They did what they had to do under those conditions. I do not blame them for what happened to me, nor do I blame my parents. This is something that Canada did to us.

The white man has stepped everywhere across this land without seeing the people and how they have been injured or incapacitated by his exploits. They have also taken our children and removed them from their communities for generations until they are no longer connected to their family and community. In the dream, I ask him if I can step on only one of his feet. What does this say about me? How have I used the white man’s systems for my own survival? I would have to say I used the systems of education but only on one of his feet. With this foothold I am not completely taken by his ideas of “civilization” or “progress” and have only used education as a tool for my survival as an Indigenous woman, as an Ininu Iskwew. I have freed myself and continue to walk in the path of my ancestors who have survived many hardships. I am walking out of that house of tragic events.

I bring in this dream of “trying to reach the door” because this is where it all began in our history together. We were supposed to be travelling along in our own canoe and boat, without interfering with each other’s lives. But the white man could not keep to himself, he had to have more: more land, more gold, more fur – more of everything that existed here on Turtle Island. He learned that by taking and removing our children we could not sustain our future. By attacking the very centre and heart of our people, our social fabric would weaken and fray – our lives shattered by this removal of our purposes in life. We lost our direction. This is what happened to my family. My parents, who loved their children, lost control of them. They were forced into submission by laws enacted by Canada to prevent their cohesion and closeness as a family. With Canada’s interference in their lives as parents, they were left with a “wait and see” approach to parenting. Where would their youngest and last child go to school? They didn’t know, they could only hope they could keep me with them at home.

No Responses to “ Finding A Way In ”

Thanks for sharing your story, Brenda Wastasecoot.

Tears, and I love you.

Thank you for sharing your story, Brenda Wastasecoot. It is so important to share and encourage empathy.

Once again, thank you for sharing your story, Brenda.

From an old moonias, thank you for sharing your story. It will help us all heal. Ekosi.

Thanks for your story, Brenda! I used to feel so sad when your siblings left. I was glad you were with us. Yes, it was a difficult life.

Thank you for sharing. I love this.

Thanks for sharing.

Thank you for sharing.

Beautiful writing. Thank you, Brenda.

Thank you so much, Brenda, for your powerful writing and truth-telling. I hope this piece is widely read.

I am so sorry for the loss sustained by your family and other Indigenous families whose lives were uprooted so heartlessly through the process of so-called assimilation and conformity. I pray you find strength in the resilience you and other survivors have displayed and use that resilience to carve out a brighter and more celebratory future.

Thank you for sharing your experience and wisdom. Our hearts open thanks to your strength. To learn more each day about the lies of the federal government, tears flow. I pray for the improvement of the living conditions of loved ones. The land is not a possession, just part of the whole. The ignorance of this natural law is the source of such pain and is man's own creation.

Thank you for sharing your story.

Thank you for sharing your story. It is very interesting. I am writing my mother's story. She spent over 15 years at Brandon Residential School, from 1923. So proud that you took the door. I have not been to the site as my mom was taken from Ontario. I hope to go this spring. I understand the intergenerational traumas. I am still doing research on the school and have not found much info on its early years.