This spring, as the world watched Egypt’s old guard capitulate to revolutionaries after weeks of social unrest, Iraq’s young democracy came under fire from its own disgruntled citizens. Fanned by the popular anger seizing much of North Africa and the Arab world, raucous uprisings swept through Iraq’s cities. Samer Muscati (JD 2002), a researcher for the Middle East division of Human Rights Watch and a freelance photographer, found himself amidst the tumult in the northern city of Sulamaniyah, where, for more than a month, university students and others took to the streets daily, occasionally clashing with police and armed goons.

Unlike their restive neighbours in Egypt, Yemen and Bahrain, Iraqis weren’t demanding regime change; they simply wanted basic public services such as electricity and water, and an end to rampant local corruption. Still, the state’s response had been swift and brutal. Some protesters had been rounded up, beaten and jailed. A collection of tents, erected to shelter demonstrators in the city’s central square, had been torched. Several youth showed Muscati fresh wounds that had been inflicted by masked thugs as security forces stood idly by. “I met with two photographers who’d had their hands broken, another journalist who’d had his ribs cracked,” Muscati recalls. “And these guys were just taking pictures.” Earlier, he’d seen footage from Baghdad of security forces with batons beating journalists, smashing their cameras, and taking their memory cards. Even in Iraq’s post–Saddam Hussein era, Muscati says, “Freedom of expression has been under attack for a while.”

Muscati is still in Sulamaniyah, where it is close to midnight when I reach him on Skype. He’s tired, and his voice betrays the kind of emotional exhaustion that comes with looking for truths in the dense fog of war. He spent the day meeting with victims and witnesses of the violent protest, but says this marks only the beginning of his inquiries into the abuses. In the coming days, he hopes to sit down with the city’s head of security to demand, in his quiet way, some modicum of accountability: Were investigations being launched into the brutality? “It’s not enough to just report on the problems,” says Muscati, whose work for Human Rights Watch makes him a kind of professional witness to human suffering. “We need to make sure that change occurs as well.”

Muscati, 38, is the last of his family in Iraq, a persistent leaf on a barren tree. Since the early 1970s, and then against a backdrop of invasions and civil wars, waves of Muscati’s cousins, aunts and grandparents have sought refuge abroad. “They fled during the Iran-Iraq War, during the First Gulf War, during the sanctions, after the 2003 war and the last ones fled after the sectarian violence in 2006,” he says. “My parents understand why I’m here, but it’s difficult for them. They say, ‘We came to Canada to give you a better future. Why the hell are you going back?’”

Though free from the tyrant’s grip, Iraqi citizens who find themselves on the wrong side of the law − and even those who don’t − have reason to fear the authorities. Torture was endemic in Iraq’s shadowy legal system under Saddam, who maintained control by keeping political dissidents locked up in barbaric conditions or simply “disappearing” them. It’s now eight years since Saddam was forced from power, but injustice has a long half-life. Torture − as both an interrogation technique and instrument of mass terror − was so much a part of Iraq’s misrule of law that it has proved difficult to eradicate.

Last year, Muscati and Human Rights Watch uncovered a disturbing scene that could have been lifted straight from Baathist Iraq: a secret prison, operating far beyond the Ministry of Justice’s reach, where special forces reporting directly to the prime minister’s office systematically tortured terrorist suspects to gain false confessions. Rumours of the prison had been swirling among the families of the disappeared for several months. In early 2010, Muscati and a colleague, following a lead from a Los Angeles Times story, spent hours arguing with guards for access to 300 men being held at the Al Rusafa Detention Centre (they had been moved there from the secret prison). Finally, the guards stripped Muscati and his colleague of their recorders and cameras, and told them they had three hours to speak with 42 of the men. During the interviews, as one prisoner after another showed Muscati the scars left by his interrogators, it became clear that the abuses had been as routine as they were brutal. “Security officials whipped detainees with heavy cables, pulled out fingernails and toenails, burned them with acid and cigarettes, and smashed their teeth,” Muscati later wrote in his report, which captured national attention in Iraq.

Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki quickly denied any knowledge of the secret prison, but an internal memo from the American Embassy showed that the security forces running the site were taking their orders from his office. Worse, the memo reported, the commandos, who regularly work alongside U.S. special forces, were “involved in detaining prominent political figures as well as other Iraqis who have little apparent connection to terrorism or insurgent activities.”

When American tanks rolled into Baghdad in 2003 and toppled a giant statue of Saddam in Firdos Square, the liberators were said to be tilling the soil for a liberal democracy. But widespread looting, a feckless Coalition Provisional Authority and sectarian civil war soon eroded any hopes of an Iraqi Spring. Muscati offered me this assessment: “This is a place where violence is festering. The concern is, how do you deal with it in a way that doesn’t create new terrorists, alienate a large part of the population or trample on people’s human rights?” It’s an ugly truth that the security gains in Iraq since late 2006, when some 2,800 Iraqi civilians were being killed each month, have come at the cost of democratic principles. The consequence of al-Maliki’s security trump card, Muscati says, “is less space for journalists to operate, less opportunity for protesters to dissent and harsh methods for those accused of terrorism.”

As one voice of concern among Baghdad’s many nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), Muscati is asking Iraqi ministers to elevate human rights – the paving stones of a durable democracy – to a place alongside counterterrorism. He finds allies when and where he can. “The government may not be perfect, but it’s responsive,” he points out − and this makes Iraq different from other Arab states. Since his discovery at Al Rusafa, Muscati has found unambiguous evidence of torture in two more prisons, known − without apparent irony − as Camp Honor and Camp Justice. Each prison holds hundreds of men swept up in broad counterterrorism raids that are now commonplace in Sunni neighbourhoods. The minister of justice and the minister of human rights were both willing to speak with Muscati when the new abuses came to light, and, in March, a parliamentary investigative committee forced the closure of Camp Honor. “We are making progress,” says Muscati. “It’s not all negative. It’s just difficult − there’s so much more that needs to be done.” The prime minister continues to stonewall reporters on human rights. And no one expects indictments against the torturers to be handed down soon, if ever. In the face of such obstacles, Muscati possesses a kind of Herculean persistence; he has worked closely enough with the prime minister’s office in Baghdad to recognize how internecine Iraqi politics can be. “Al-Maliki has one of the most difficult jobs in the world,” Muscati says. He’s inheriting a new institution, surrounded by religious leaders, political interests and regional neighbours who all have a vested interest in meddling. “It’s a terrible predicament to be in.” Though the security situation is improving, Muscati wonders how long Iraqis will tolerate a government that allows its citizens to be brutalized. Where lies the tenuous line between adolescent democracy and infant police state?

Muscati’s heritage is Iraqi, but he grew up in “sleepy Ottawa,” the eldest son of two ambitious young scientists who left Baghdad in the 1970s to pursue graduate school in the West. After pit stops in Iran, Germany and England, both his father (an electrical engineer) and his mother (a chemist) received their PhDs in Canada. “I joke with my brother” − also a lawyer − “that we’re the least educated people in our family,” Muscati says.

The boys – watched most days by their grandmother, who spoke no English – were bilingual. Owing to parental edict, Iraqi Arabic was their Canadian home’s lingua franca. But if Muscati stuck out in high school, it had less to do with his language skills or skin colour than with his serious mien. “I was always kind of a nerd,” he says. “I was reading books about Gandhi and non-violence and pacifism when other kids were doing what kids are supposed to do.” He quit eating meat at 14, a commitment he still keeps today, and began “trying to think of peaceful revolution.”

While majoring in environmental studies at Carleton University, Muscati worked on the student newspaper and became the parliamentary bureau chief for the Canadian University Press’s news wire, covering Ottawa’s political scene. Once out of school, he interned with Reuters then jumped to the Globe and Mail, where he worked as an editor for three years. “To be honest with you − and I shouldn’t be saying this − the reason I became a journalist wasn’t because I had a love of writing or I wanted to be objective. I saw it as a great tool for promoting issues.” A mentor at the Globe pushed him to pursue his interest in law, telling him that editorial work could wait. He arrived at the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Law as a second-year transfer student interested in environmental policy. But a course in human-rights law left him deeply moved, so he turned his attention to that.

After earning his law degree, Muscati went to work as a finance lawyer for a big firm in Boston. “It was the worst year of my life,” he says. “It was horrible.” Telling himself that he was merely renting − not selling − his soul to the corporate world, he spent his days negotiating lending terms between banks and their commercial clients. In retrospect, he says, it provided him with a useful set of white-collar tools, such as “how to deal with difficult people.” With his eye on a master’s in international human-rights law at the London School of Economics and Political Science, he “tried to lead a very impoverished lifestyle” and quickly paid off his loans.

Muscati had long resolved to pursue legal work in Iraq but the dream remained an impossible one while Saddam was in power. The 2003 invasion opened the door to development, humanitarian and rights groups, and, in January 2006, after two years of hopscotching the globe with his master’s now in hand, Muscati arrived in Baghdad. As part of a private consultancy firm, contracted by the U.K.’s Department for International Development, Muscati and his colleagues helped build Iraq’s first Cabinet Office from scratch. Sectarian violence in the country was approaching a tenor pitch, and inhabitants of heavily fortified Baghdad lived under a siege mentality. Working out of the British Embassy, Muscati, clad in ballistics vest and helmet, travelled with bodyguards in an armoured vehicle and never left the Green Zone. Home was a concrete bunker. Getting from the compound to the airport – a distance of a few miles – required a helicopter. “Mortars were coming in daily,” he says. “The security situation was horrible. Every few months, one of the people we were working with would be kidnapped or killed.” Slowly, his team trained 16 new bureaucrats − the foundation of a new democracy. Then one of the security guards blew himself up, maiming the deputy prime minister and killing a number of staff. When the Human Rights Watch position came open in Toronto in 2009, Muscati happily gave up his itinerancy and moved home.

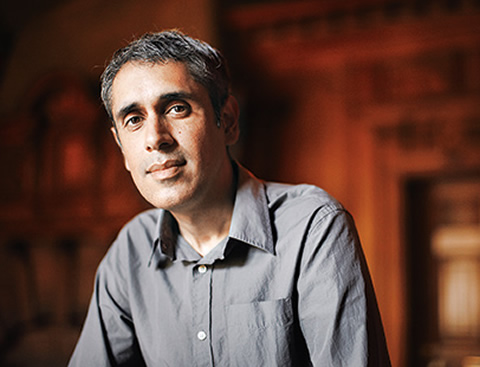

On the ground in Iraq, Muscati’s linguistic arsenal, olive complexion and reporter’s instincts allow him to move easily around the country. His hair has gone silver early, perhaps from day-trading in human sorrow, but the look lends him a worldweary authority. He’s as skinny as a carrot, with a strong nose and eyebrows that do enough worrying for two. His soft-spoken demeanour, bordering on shyness, may be his best weapon. “He likes to win people over with his humour,” says his partner, Sandra Ka Hon Chu (LLB 2002). “And he usually does.”

Muscati – who tells me he sees more of Iraq from spending a single day in the Red Zone than from living for months in the Green Zone – travels with only a satellite tracer, which registers his location every quarter-hour, for security. “It’s just me and my muscles,” he jokes. When a family in a far-flung province opens its door to find Muscati standing outside, notebook in hand, they often look up and down the street for his armed guards. “They’re always delighted. It shows that we do care and have come all this way − and are risking something − because we want to help. It gives us some street cred.” (Other NGOs often ask their Iraqi sources to make the trip to the Green Zone, “which is a horrible process for local Iraqis to go through, with all the checkpoints,” says Muscati.) Most Iraqis are familiar with Human Rights Watch, which spent the Baathist years reporting on the regime’s laundry list of crimes, and Muscati is often deluged with testimony and information. He may do as many as 20 interviews a day, or as few as three; because of Baghdad’s maze of checkpoints, he says, it takes an hour just to get across town. Free from the capital, though, a month-long reporting trip will take him to at least a half-dozen cities. The carte blanche to travel is integral to deep investigative work, but it’s a source of constant anxiety back home. Every time the media report a bomb blast, his cellphone inevitably rings. “Of course, Iraq is a very big country,” he says.

Life on the road can be solitary, and a little bleak. Muscati spends six months of the year in Iraq and the United Arab Emirates, and the other half at home in Toronto, where Human Rights Watch keeps a regional office. Working with an Iraqi “fixer,” a street-smart guide who knows the lay of the land, Muscati spends hours in hospitals, homes and ministry buildings, doing the exhaustive shoe-leather reporting that the news media has all but forsaken in Iraq. To formally report rights violations, he needs hard evidence: firsthand testimony, photos, police reports, medical records. He needs to interview victims or their grieving families – but he also needs to seek comment from the alleged perpetrators. And any paper he writes goes through weeks of vetting – by specialists, regionalists, in-house lawyers – before it’s published. “All we have as an organization is our credibility,” he says.

Human Rights Watch, whose mission is equal parts fact-finding and advocacy, has built its reputation on being apolitical and single-minded in its concern for the basic and inalienable rights a democracy promises its citizens. The group’s ability to press illiberal governments on concrete policies – on female genital mutilation in Kurdistan, for example, or migrant domestic labour rights in the United Arab Emirates – depends on simultaneously enfranchising and criticizing them. Playing ally to some ministries and gadfly to others requires a certain delicacy. “Sometimes these meetings are tense,” Muscati says of the advocacy work. “It’s difficult to have an outside group coming in and telling you how to do your job.” While the politics of the job can be challenging, the emotional toll can be especially draining. “People talk about the risks and dangers, but that’s not as difficult to manage as the sadness,” says Muscati. “That’s what really gets to you. Given that there’s been two decades of strife, conflict, turmoil and sanctions, every family has been traumatized.” The miles he’s travelled since leaving Boston and its plush corporate digs have clearly affected Muscati. “My idealism has been tarnished somewhat since I left law school, after working in Iraq and Rwanda and East Timor and seeing what humanity is capable of. I’ve lost a lot of my innocence.”

And so it is that Muscati’s job has become his life’s work. The nine-to-five has become a courtship with human malevolence and human goodness. But he can’t quit it. On an investigative trip to northern Iraq this spring, he found much of the region mired in desperate, frustrated anger: after bloody national elections in March 2010, bickering ministers put on a political sideshow that lasted more than eight months as they tried to form a government. “Iraqis are pessimistic, and they have a right to be,” he says. American forces and advisers are beginning their final withdrawal, even as many of the political and social institutions they’ve spent eight years trying to seed have failed to take root and mature. The electricity still constantly fails, corruption pervades the government and essential goods are in chronic short supply. But Muscati’s sense of possibility, of the good that may yet come, is unflagging. “To do this job, you have to be an optimist,” he says. “Otherwise, at some point, you have to stop.”

Kevin Charles Redmon is a freelance journalist and was a 2008 Middlebury Fellow in Environmental Journalism.

Recent Posts

People Worry That AI Will Replace Workers. But It Could Make Some More Productive

These scholars say artificial intelligence could help reduce income inequality

A Sentinel for Global Health

AI is promising a better – and faster – way to monitor the world for emerging medical threats

The Age of Deception

AI is generating a disinformation arms race. The window to stop it may be closing

One Response to “ The Watchman ”

Too bad Samer Muscati's reputation as a human rights researcher and activist is severely undermined when he let's himself be interviewed by that left-wing rag of a media organization known as Democracy Now.