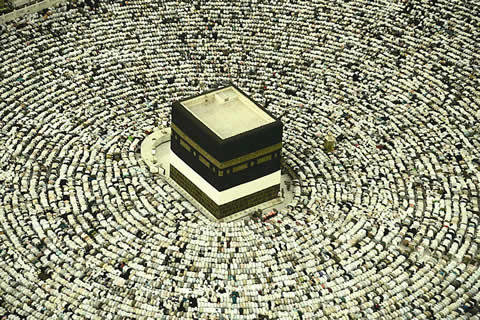

When most people think of Mecca, they summon up images of thousands of Muslims making a once-in-a-lifetime pilgrimage, or “haj,” to the centre of the Grand Mosque in the Saudi Arabian city of 1.5 million.

But for Amer Shalaby, a professor of civil engineering, Mecca poses a uniquely inspiring transportation riddle. During the annual pilgrimage period, and also after evening prayers during Ramadan, as many as three million faithful will converge on Mecca’s sprawling mosque precinct, the holiest place in the Islamic world. In terms of crowd control, logistics and transportation, there’s simply nothing comparable. “I myself haven’t ever seen anything like it.”

Over the past three years, however, Shalaby, an expert in transportation modeling, has been involved in an extensive effort by the Saudi government and the municipality of Mecca to develop a transportation master plan for the region. With the world’s Muslim population growing quickly, local authorities have realized they need to prepare for an even more crowded and concentrated future.

While on sabbatical in Qatar, Shalaby advised a group evaluating a handful of proposals to create a transit network capable of carrying crowds seen only in Tokyo or Hong Kong. With literally tens of thousands of tour buses converging on an area about the size of Toronto’s downtown core, the challenges are extreme: Besides parking and the provision of basic amenities (food, water and washroom facilities), local officials have to be prepared for both high temperatures and extreme weather, such as dust storms and flash floods. (That’s because Haj and Ramadan follow the lunar calendar, and occur at varying times of the year).

Then there’s the city’s aquifer, which plays a spiritually important role in the Old Testament story of how Mecca came to be such a sacred site. When the project management team recommended a network of eight ultra-high capacity subways in a radial configuration converging on the Mosque district, the planners had to route the tunnels well away from the aquifer, which supplies Mecca’s drinking water. “This was something you couldn’t really tamper with,” says Shalaby, noting that each subway line must be able to carry at least 75,000 passengers an hour. (By comparison, the TTC’s Yonge line has an average peak ridership of 27,000 passengers an hour.)

Shalaby’s work has led to a research contract between U of T and Mecca authorities, as well as a $100,000 donation for a scholarship for the study of “large event management” from Riyadh-based private equity investor Mazen Hassounah, who obtained his graduate engineering and planning degrees from U of T.

While the Haj crowds are in a class by themselves, Shalaby notes that Mecca Mayor Osama Al-Bar wants the city to become something of a lab for developing and testing transportation strategies for international sporting events, such as Toronto’s 2015 PanAm Games. “There was a lot really to be learned there.”

Recent Posts

People Worry That AI Will Replace Workers. But It Could Make Some More Productive

These scholars say artificial intelligence could help reduce income inequality

A Sentinel for Global Health

AI is promising a better – and faster – way to monitor the world for emerging medical threats

The Age of Deception

AI is generating a disinformation arms race. The window to stop it may be closing