Program: SDGs@UofT

Launched: 2023

Mission: To bring together the entire university and external partners to create a global powerhouse of knowledge and action on the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals

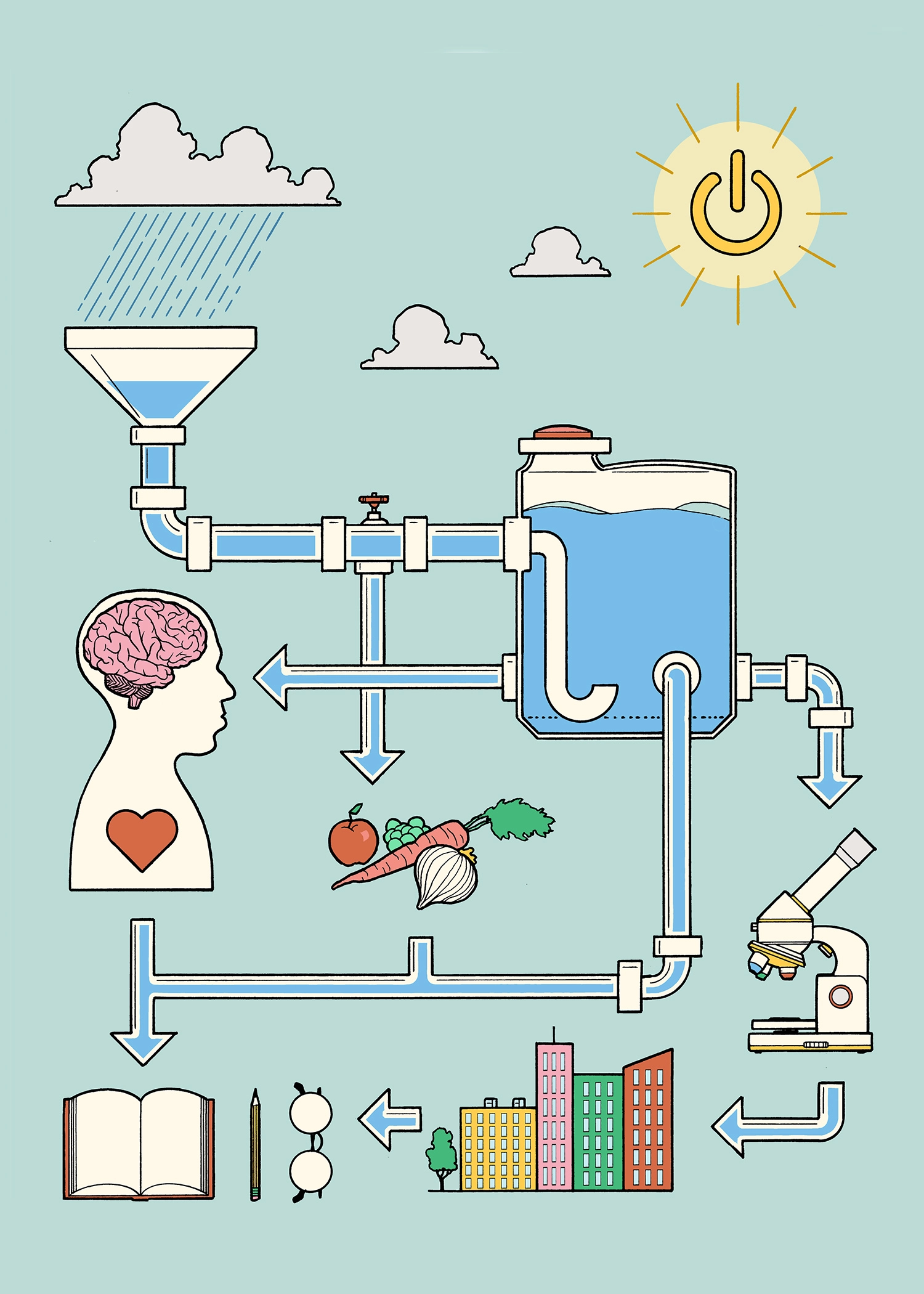

Early in her academic career, Amy Bilton, a mechanical engineering professor at U of T, worked on an innovative way to remove salt from well water in the Yucatan region of Mexico. The technology made the water fresh enough to drink. But in many projects, she observed, the equipment eventually fell into disrepair because the local community was unable to maintain it after the engineers left. For Bilton, whose parents worried about the water levels in the well on their own farm, it was a lesson in the limitations of one discipline solving complex problems.

Today, Bilton includes a sociologist and urban planner on her team to help understand how people use the salt-removal systems that engineers install. The social scientists survey local residents to learn about barriers to using the equipment – a lack of technical know-how, for example, or safety fears that could be addressed with information and trust-building.

“You can develop the best technology in the world, but who cares if people don’t want to use it?” notes Bilton, who directs U of T’s Water and Energy Research Lab. “Engineers are great at developing technology, but social scientists make sure we’re building something that works for the local community. It’s a totally different skill set.”

Recently, the team installed rainwater-collection systems in Guadalajara, Mexico, and learned through follow-up surveys that local uptake was good. This summer, sociologist Yu Chen, a research associate at U of T’s Centre for Global Engineering, and Nidhi Subramanyam, an assistant professor of geography and planning, returned with a follow-up survey to learn why the technology is working for this community when similar projects around the world fall flat. In particular, they are interested in knowing how people have adapted the designs to their own particular needs.

Bilton and her colleagues belong to a growing group of researchers who see water – too little and too much – as deeply tied to other global challenges, such as food insecurity or climate change. They also recognize that these problems tend to have the greatest impact on the world’s lowest-income regions. According to the United Nations, 2.2 billion people around the world lacked access to safe drinking water in 2022 – most of these in the Global South. Almost half the world’s population lives without safely managed sanitation. Bilton’s team estimates that in Guadalajara, poor people typically spend as much as 10 per cent of their income on water.

This is why Bilton has teamed up with a surprisingly diverse group of researchers at U of T who are all working to advance or study the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals – including number six: access to clean water and sanitation for all. The goals are a kind of blueprint for peace and prosperity around the world, and the newly formed “SDGs@UofT” serves as a nexus for the entire university community to access each other’s expertise and ideas. The group is based at U of T Scarborough but engages faculty from all three campuses. Researchers include a Shakespeare scholar and a media studies professor, along with engineers, physicians and social scientists.

“All of the sustainable development goals are equally important, and they are designed to be tackled together because we need to stop pitting food against water, or the environment against development,” says Nicoda Foster, the initiative’s associate director. “Instead, we need to develop solutions that work on many levels. I believe every single faculty and staff member, student and alum at U of T has a role to play if we are to have any hope of meeting our targets.”

Engineers are great at developing technology, but social scientists make sure we’re building something that works for the local community. It’s a different skill set.”

Foster has a personal connection to the development goals she helps to advance. As a child visiting her grandmother in rural Jamaica, she took her turn waiting in line with a bucket at the community’s only water pipe. That experience propelled her into a career as a public health researcher with a strong interest in equity, and then to the sustainable development goals.

But Foster has no illusions about the challenges involved, particularly after the COVID pandemic. All UN member states have agreed to meet the 17 goals by 2030 – but few experts believe it will happen. To achieve the water goal, for example, the UN estimates that the pace of annual progress would have to accelerate by 600 per cent. Foster believes that tapping into the expertise of university researchers around the world will help.

Erica Di Ruggiero, an associate professor at U of T’s Dalla Lana School of Public Health, serves as the initiative’s inaugural research director. She is passionate about connecting researchers from the humanities with the earth, health and social sciences to tackle not just one or two, but four or five of the UN goals at once. This work is guided by a growing realization that the world’s wickedest problems, such as climate change, hunger and poverty, didn’t arise in a vacuum and won’t be solved in isolation. They understand that solving these problems means tackling the deep inequities that seed them.

“The problems we’re addressing aren’t necessarily new, but they need new solutions in the current global political and economic architecture,” says Di Ruggiero, an expert in global health and health policy. “We can’t go back to the same well for the same kinds of solutions for complex problems that are not just technical, but social and economic.”

Another affiliate, Carmen Logie, a professor at U of T’s Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work, has observed the ripple effect of water insecurity. She has seen the way it can exacerbate community and household violence, gender inequity, infectious diseases – and sometimes end the dream of education. Logie, whose research focuses on HIV, is currently studying ways to prevent sexually transmitted infections and unplanned pregnancy among teens in Uganda’s Bidi Bidi refugee settlement, and in another Kenyan refugee settlement stricken by drought.

In the camps, there’s never enough water. Efforts to find it put people in danger. In one of the bleaker scenarios, a menstruating girl who wishes to attend school the next day might leave her zone of the camp after dark to look for water to wash herself or her uniform. She is then at increased risk for sexual assault, with its ensuing mental health effects and infection risks. If she becomes pregnant, her chance of schooling is likely over, says Logie.

This example alone shows the connection between water insecurity and at least half a dozen other UN goals. And it’s the reason a social work researcher like Logie is so focused on water.

“Young people talk about the concept of suffering and how water is life,” she says. “Sanitation is part of this. When we ask young people in refugee camps what they want, sometimes it’s as simple as a $5 lock on a latrine to give them privacy. But then, how do you stop snakes from dropping into those latrines so people aren’t afraid to use them? That requires a totally different expertise.”

Last year, Logie attended the UN’s World Water Week in Stockholm, Sweden. The conference was full of engineers working on technical solutions to water shortages, and they were surprised to see a social work researcher.

“It left me wondering how we get these different disciplines to talk to each other,” she recalls. “How can we get even just the people researching water and health goals to work together? If we know there is going to be a drought or flooding, how can we ensure that people living with HIV can maintain access to their medications and avoid missing life-saving doses?”

Recently, Logie took a welcome step in that direction by joining U of T’s Sustainable Development Goals initiative. She hopes to meet climate change experts or people working on ways to manage menstruation that don’t require water.

For Foster, Di Ruggiero and the other researchers, the UN’s goals are not sacrosanct – certainly not immune from criticism of priorities. But they are a way to organize the world around the biggest challenges to peace and prosperity, equity and justice. And they help show that these challenges are connected to each other and to everyone. The clock is ticking, and the stakes are high.

“When I think about these goals, I see my past,” says Foster. “I also see the present because there are so many other children lining up at water pipes right now with their little buckets. And I see the vision for the future, because this should not be.”

No Responses to “ A Blueprint for Global Prosperity ”

Jeffrey Sachs, the director of the Center for Sustainable Development at Columbia University and president of the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network, is a well-meaning economist/diplomat and one of the world's best geopolitical analysts. He understands power and how the U.S., in particular, works. Yet, I find his initiatives contradictory and overly optimistic, as evidenced by his period as an advisor in Russia (on the transition to a market economy), Bolivia (on combatting hyperinflation) and Africa (on alleviating poverty). The UN's sustainable development goals are another example of this. How can one reconcile capitalist growth with many of the UN's goals?