In autumn 2016, a man holding an adolescent girl in his arms arrived at the Canadian Centre for Refugee and Immigrant Health Care, a free walk-in clinic in Scarborough, Ontario. The clinic hadn’t opened yet, but the man was kicking at the door, desperate to get in. The girl was his 12-year-old daughter, “Miriam.” She had been losing weight rapidly, and was now confused and having trouble breathing. Her dad had put off seeking help, believing she had the flu and would get better. In addition, he had no money for fees. Then he heard about this place. It was free.

The clinic’s medical director, Paul Caulford (BSc 1972, MSc 1975, MD 1978), happened to be there already and saw them right away. He diagnosed the girl with Type 1 diabetes. Her blood sugar was dangerously high and Miriam was entering a coma. She had to go to hospital, Caulford told them, or she would die. A staff member drove the family to a Toronto hospital, where Miriam was admitted and treated. About five days later, she walked out stable and safe – and with a bill for more than $20,000.

The family were refugees who had fled Ethiopia, but they’d made a classic mistake: they had not claimed their refugee status at Toronto’s Pearson Airport, where they entered the country. If they had, they would have been entitled to something called the Interim Federal Health Program, which provides health care similar to OHIP. It would have covered doctors, hospitals and diabetes supplies. But because they had made their claim a few days after arrival, at an office of Immigration, Refugee and Citizenship Canada, they were entirely uninsured. Refugee health care wouldn’t kick in until their claim was processed at a meeting scheduled for at least a month. Miriam would almost certainly have been dead by then.

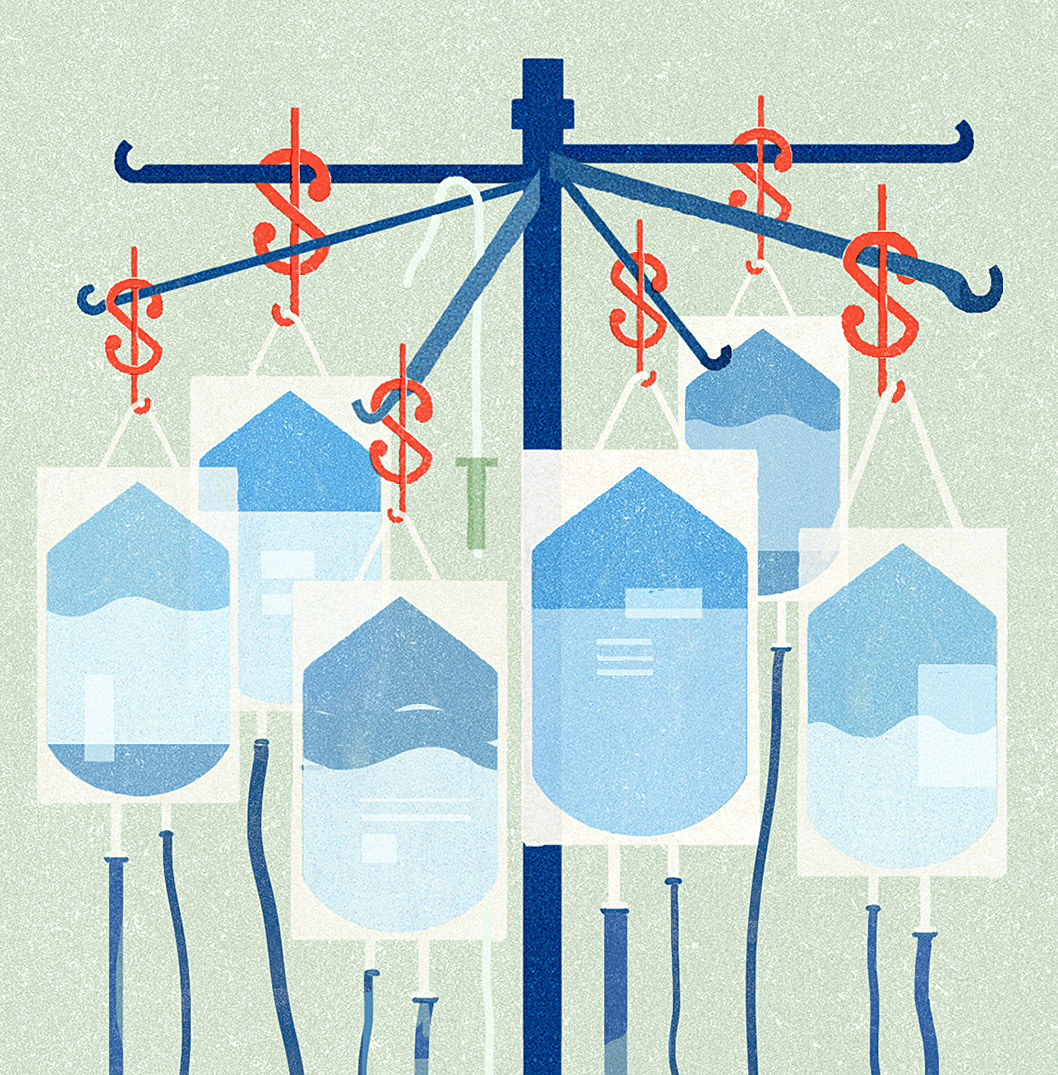

Such are the unlucky people among us whose precarious immigration status leaves them without the protection of basic health coverage. Refugees who don’t know the system. Failed claimants who lose health care while they appeal. Temporary foreign workers between jobs. Students who overstay their visas. People who sneak into the country for a better life and end up living underground.

Just because they don’t have status doesn’t mean they don’t get sick, says Caulford. “They break bones, they get pneumonia, they get appendicitis,” he says. “They can never afford the bill.” Caulford has seen the number of people seeking help at his clinic go up eightfold in the 20 years since it opened.

Many of Toronto’s doctors think that health care should be provided to all people who reside here, says Meb Rashid, a professor in U of T’s Faculty of Medicine and a family doctor at Women’s College Hospital’s Crossroads Clinic, which offers care to newly arrived refugees. “Many would argue, and I would be one,” he says, “that health care should not be connected to immigration status.”

I think we need to use the frame of human rights when we’re talking about health – health care as a human right.

That is a key purpose behind Toronto’s designation as a Sanctuary City: that all people get access to municipal services regardless of immigration status. The problem is that the city only has control over what the city delivers, and in the realm of health, that isn’t a lot, says Dr. Ritika Goel, who is part of the family health team at St. Michael’s Hospital and a lecturer in U of T’s Faculty of Medicine. Toronto Public Health administers vaccines and runs groups for new parents, among other things, but the heavy lifting of health care is done by the province. “Sanctuary City doesn’t substantially improve people’s access to health care,” says Goel, who also provides shelter-based health care through Inner City Health Associates in Toronto.

Patients who go to an Ontario hospital without coverage will most likely be billed, she says. Many hospitals demand cash or a credit card up front. Some hospitals follow up with collection agencies. “So it’s not a symbolic bill,” says Goel. “It’s a real bill.”

In instances where the patient isn’t in need of emergency care and doesn’t have the money, they can be turned away. Caulford had a young patient who broke his arm when he fell out of a tree at school. Sanctuary City meant the boy could attend school like any other kid, says Caulford, but fixing the arm was another matter. Expensive treatments like surgery or cancer care are even more difficult to access, says Goel. She knows of two people who had cancer, were unable to afford treatment and died.

“I think we need to use the frame of human rights when we’re talking about health – health care as a human right,” says Goel. She is not the only one to think so. The United Nations Human Rights Committee recently chastised Canada for its record, citing the specific case of Nell Toussaint. Toussaint came to Canada from Grenada as a visitor, but stayed and worked low-wage jobs for years. Some of her employers deducted federal and provincial taxes, CPP and employment insurance premiums. But because she was without status, she was not entitled to health care. She could not afford to pay for it, so she went without. As a result of untreated Type 2 diabetes, her mobility, vision and speech were compromised.

But it’s not only philosophical, it’s pragmatic, says Dr. Anna Banerji, associate professor of pediatrics at U of T’s Dalla Lana School of Public Health and chair of the North American Refugee Health Conference. Many of these people will eventually become Canadian citizens. If a person gets sick while uninsured and suffers permanent injury, we’ll pick up the tab in the long run anyway – and that might be steeper. Or we might create new problems. Banerji recalls the case of a child who had typhoid fever. She was treated, but the bill came to more than $30,000. The dad, who was a skilled worker, fell into deep depression. “There’s no reason for this,” she says.

Goel supports a campaign called “OHIP For All,” which argues for health care for all residents, regardless of immigration status. Ahead of last year’s provincial election, the NDP topped that – and for the first time in Canada made a call for a full Sanctuary Province. But there’s little to be proud of when you compare what Canada does for people with precarious status to what other high-income countries do. “Overall, the situation is better in many other places,” says Goel. In the European Union, it is standard to provide emergency care without charge to people of precarious status, she says, and many countries offer much more. And although Canadians don’t like to hear it, there are places in the U.S. that are doing a better job of caring for the truly precarious, says Goel. Because many U.S. citizens face major health-care challenges, there are workaround systems and these can often be used to support people with precarious immigration status, she says.

“Among high income countries, I’d say Canada is quite unusual in that we tend not to even talk about this population,” says Goel. “We pretend they don’t exist.”

Improving Access to Health Care

Prof. Anna Banerji of pediatrics says it would help to open more clinics that accept patients even without an OHIP card or other coverage. Clinics such as the Canadian Centre for Refugee and Immigrant Health Care in Scarborough allow patients to be seen regardless of status before their health deteriorates, she says.

“When charged high bills they can’t afford, [undocumented patients] go underground and some of these health conditions get worse, so it’s not very cost-effective in the long run,” she says.

Prof. Carles Muntaner of U of T’s Dalla Lana School of Public Health says migrants’ access to health care is an issue inseparable from their employment status.

Certain European countries, such as the Netherlands and Denmark, do a better job of caring for migrant workers because they offer more generous unemployment benefits.

And basing access to health care on one’s immigration status or ability to pay can be a slippery slope to privatization, he says.

This is one of a five-part series entitled “In Search of Safe Refuge,” covering issues of health care, employment, detainment, shelter and education for refugees and migrants in Canada.

Recent Posts

People Worry That AI Will Replace Workers. But It Could Make Some More Productive

These scholars say artificial intelligence could help reduce income inequality

A Sentinel for Global Health

AI is promising a better – and faster – way to monitor the world for emerging medical threats

The Age of Deception

AI is generating a disinformation arms race. The window to stop it may be closing

One Response to “ In Sickness and in Health ”

Thank you so much for this important article!