There is a powerful story – almost a nightmare – embedded in the science of public health, explains Professor Esme Fuller-Thomson, who holds the Sandra Rotman Chair in Social Work at U of T’s Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work.

“You’re by a stream, and bodies keep drifting by,” she says, quoting a classic public health parable. “You rush in to try to rescue them.” You do what you can, she adds, to save lives.

“But nobody’s questioning who’s throwing the bodies in upstream.”

Fuller-Thomson is an exception. Seeking not just the immediate causes of human illness, but the causes of those causes, her research has helped pioneer a new frontier in the emerging science of social epidemiology, revealing startling and often disturbing insights into the deep determinants of many common diseases.

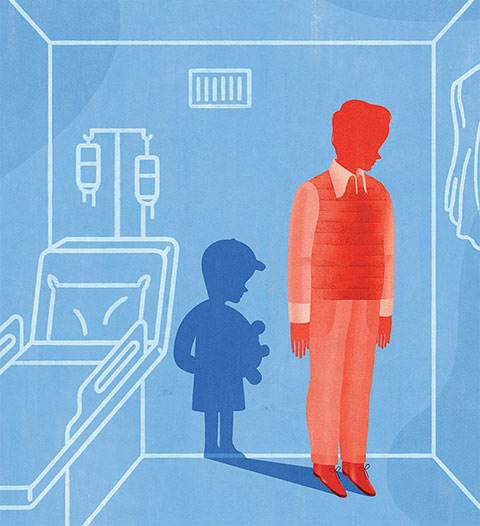

Fuller-Thomson, who is also the director of the Institute for Life Course and Aging, has published 28 articles examining the link between childhood maltreatment and many adult health problems, including cancer and heart disease. Her conclusion is simple: Child abuse is harming lives to an extent never previously imagined. Even abuse survivors who develop none of the debilitating habits that often grow in response to childhood trauma still run a significantly higher risk of these diseases than adults who suffered no such trauma in childhood.

Combined with emerging scientific insight into the biological processes that can turn past trauma into future illness, Fuller Thomson’s research holds profound consequences for social policy – both in the broadest sense of public education and the urgent need to ensure that all young victims of abuse receive treatment to help dispel the ominous shadows that darken their future lives.

A third-generation social worker whose grandmother trained in the east end of London in 1919, Fuller-Thomson began her career far downstream from the terrain she now explores, working at a free women’s health clinic in a blue-collar neighbourhood of Montreal in the 1980s.

“As a social worker, you almost never get clients who want to see you,” says Fuller-Thomson, now a busy mother of four children, prolific researcher, teacher and member of no fewer than six book clubs. “But this clinic had a long wait-list and anyone who wanted to talk about any issue could come in and see a social worker.”

And come they did, seeking advice to deal with a vast and daunting array of conditions typical of hard lives lived at the bottom of the heap. “Many, many of them had serious health issues – morbid obesity, heart disease, diabetes,” Fuller-Thomson recalls. “I could just see there was this huge cumulative disadvantage of physical health, mental health and early adversity.”

At the time, discussion of what researchers now call “the social determinants of health” was just beginning, prompted by the famous Whitehall Study of British civil servants in the late 1960s and 1970s, which showed that low social status drastically shortened lives. Fuller-Thomson discovered that reality – and her vocation – head-on in Montreal.

One striking fact stood out amid the multi-faceted hardships she helped to mitigate as a neophyte social worker: Although the people who visited the clinic were dealing with a wide variety of problems, many – about 60 per cent of them, she estimates – were incest survivors. “That was when people were just beginning to talk about incest for the first time,” Fuller-Thomson says. “It was considered too shameful to discuss it before. I don’t think I knew what the word meant till I was 20.”

That early experience gave her a crucial insight into a reality still clouded by taboos, one continually reinforced by her subsequent research: that all forms of child abuse – sexual, physical and emotional – remain rampant in our society. “The prevalence of child abuse is much higher than people think,” she says. “If you’re walking around with polio, people see that. But these are internal scars.”

Victims “protect themselves,” she adds. “If you look around any room, the chances are fairly high that there are both sexual and physical abuse survivors there. They’re among your friends, your colleagues, the people in the coffee shop, but you wouldn’t have any sense of that. There are child-abuse survivors in every income level, of every ethnicity, in every age group and in every region of the country.”

The evidence is not only hidden, it’s sometimes dismissed once uncovered. Even today, Canada remains one of the only developed countries that permits the corporal punishment of children. Section 43 of the Criminal Code, dating from the Victorian era, is often used successfully to acquit caregivers and others facing criminal charges in documented cases of abuse. The burden of shame among survivors is made heavier by such permissions, explicit or otherwise.

Fuller-Thomson’s early experience in Montreal did little, however, to suggest just how formative early abuse had been in the disordered lives of the clients she tried to help. “It was just too messy,” she recalls. “I didn’t see any pattern there except that people who’ve had a hard childhood often have a fairly hard adulthood, too.”

The young social worker’s understanding of the issue changed in 1998 with the publication of a landmark study led by Dr. Vincent J. Felitti of the Kaiser Permanente Health Maintenance Organization. Felitti and his colleagues surveyed 17,421 patients covered by Kaiser for signs of what they called “adverse childhood experiences,” including a history of physical and sexual abuse, domestic violence, or parents who were mentally ill, addicted or incarcerated. They then correlated those experiences with their patients’ known health histories.

The results were startling: Those who had experienced childhood trauma were markedly less healthy as adults than those who had not – and the more types of adverse experiences they’d had, the worse their health. Those with four or more types were almost two-and-a-half times more likely to have contracted a sexually transmitted disease, almost four times more likely to have developed chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and 12 times more likely to have attempted suicide.

Even if they developed none of the bad behaviours known to hasten heart disease, adult survivors of child abuse were still 45 per cent more likely to suffer from heart disease than non-abused peers

Studying this emerging research while on sabbatical with her family in France a decade ago, Fuller-Thomson was intrigued. The Felitti study provided an incomplete but seminal answer to the question that had driven her career since Montreal: Who gets to be healthy, and why? She decided to dig in and find out. “I was fascinated by the hypothesis, but I wasn’t completely convinced until I could jump in and look for myself,” she says. “I thought the pathway that would really explain these associations is that children who had horrible childhoods would self-medicate. They try to make themselves feel better by smoking, by overeating, by excessive drinking – and it’s those things that are going to put them at risk.”

Fuller-Thomson threw herself into the research, using two surveys of American and Canadian populations large enough to support the statistical winnowing necessary to better separate cause from coincidence – about 25,000 people altogether. She started with heart disease, one of the leading causes of premature death in North America, and found a strong association between child abuse and heart disease later in life – just as Felitti had before her. The association remained, even after she took into account the differences in the respondents’ age and sex.

“Then I said, ‘Wait a second, when I put in your smoking and your drinking, inactivity and obesity, I bet that direct association is going to go away.’ In other words, it’s going to be totally accounted for by the fact that those kids who were abused developed unhealthy behaviours.”

But she was wrong. “It didn’t change very much at all when I controlled for those variables,” she says. “The direct connection wasn’t attenuated.”

Even if they developed none of the bad behaviours known to hasten heart disease, adult survivors of child abuse were still 45 per cent more likely to suffer from heart disease than non-abused peers.

Using the same large datasets, Fuller-Thomson turned her attention to other physical diseases, and the same pattern emerged. Most disturbingly, she discovered that abuse survivors were 49 per cent more likely than others to contract cancer. And when she controlled for more than a dozen lifestyle factors known to promote cancer – smoking, drinking, inactivity, obesity – the number hardly budged, dropping by just a few percentage points. “I put in 15 other risk factors for cancer, but that direct association was incredibly robust,” Fuller-Thomson says.

To clarify what this means, she posits two middle-aged men: both non-smokers, moderate drinkers, non-obese and reasonably fit. If the only difference between them was that one had suffered physical or sexual abuse as a child, that man would be 45 per cent more likely than his peer to contract cancer.

This finding had a profound effect on Fuller-Thomson. “I had not at all thought there would be an association with cancer,” she says, describing her decision to investigate the potential link as “totally exploratory.”

Stress is thought to affect the speed at which cancer develops, she says, but not to cause it. “From what we know, the fact you have cancer or don’t have cancer shouldn’t be associated with stress. But our findings were perplexing, suggesting that those who had been abused during their childhood had higher odds of contracting cancer, regardless of whether they followed a healthy lifestyle.”

In subsequent studies, Fuller-Thomson discovered that adult survivors of childhood abuse also face greater risk of migraines, osteoarthritis, ulcerative colitis and a host of other physical disorders. In almost every case, the experience of childhood abuse was strongly associated with increased risk – even after taking into account the effects of behaviours known to imperil physical health.

Other results were equally intriguing. Previous research had shown a clear relationship between child abuse and irritable bowel syndrome, but when Fuller-Thomson controlled for depression she found that the association disappeared: People who had been abused yet didn’t succumb to depression had no greater risk of developing the syndrome.

The closely related disease of ulcerative colitis was another matter: Fuller-Thomson showed a robust link between it and early abuse, both physical and sexual. And yet early abuse had no effect on a person’s likelihood to develop another similar physical problem: Crohn’s disease.

Such distinctions strongly suggest that abuse may trigger a very specific set of physiological changes. Only recently, however, has the potential identity of these changes begun to emerge.

As a social scientist, Fuller-Thomson came to a point in her research that would have been familiar to Dr. John Snow, her Victorian predecessor. His famous map marking London cholera deaths identified contaminated water as the culprit, and simultaneously overthrew a long-prevailing theory that cholera and other diseases were transmitted by “miasma” – in the air. Although Snow proved conclusively that cholera was water-borne, decades passed before scientists finally accepted germ theory to explain the transmission of infectious diseases.

By what possible mechanism could childhood abuse be transmitted directly into adult disease? “That left me a bit befuddled,” Fuller-Thomson admits.

Having eliminated all the usual answers, she turned to the work of Dr. Clyde Hertzman at the University of British Columbia, at the time a world-leading researcher on the social determinants of health. Focusing on the long-term effects of child poverty, Hertzman had coined the term “biological embedding” to explain how bodies “remember” and revisit trauma throughout their lives. “What he was saying is that early experiences get under the skin, and they change the way we react to stress for the rest of our lives,” Fuller-Thomson says.

The explanation makes sense intuitively, she adds. “When you’re a child and you’re in a totally abusive environment, you have to be hyper-vigilant. Is Dad going to come home drunk? Do I have to watch out? The idea of being very alert all the time – having a quick fight or flight response – is hugely protective if you’re in that type of environment.”

But that conditioning extracts a price. “What it means is that your body will react to any subsequent adversity as though it’s a five-alarm fire. And eventually that wears things out and makes you more vulnerable.

“If you’re in a home environment where that’s the most scary place to be, you can never let your guard down,” Fuller-Thomson adds. “It totally makes sense that you might get sick, because there’s never a place you can go and not be vigilant about your personal safety.”

Early trauma may rewire the brain, opening circuits that help survival in the short term but ultimately harm the body they are designed to protect

The effort to understand how chronic anxiety in childhood might result in physical disease decades later led Fuller-Thomson to examine research in the emerging field of epigenetics, which examines how external factors, especially stress, can produce heritable changes in gene expression without changing genes themselves.

Fuller-Thomson points to the research of Dr. Michael Meaney at McGill University, who examined the role of mothering in rats. Meaney’s work showed not only that rat pups raised by nurturing mothers grew up to be much calmer adults than rat pups raised by less nurturing mothers, but also that their mothers’ attention produced physical changes in the pups’ brains. Licking – the rodent equivalent of cuddling – triggers an epigenetic “switch” that activates a dormant gene that helps decrease the concentration of stress hormones in the body.

“We’re bringing in pieces of evidence from everywhere we can possibly find them, and until further notice that’s the best possible hypothesis,” Fuller-Thomson says. “My interpretation is that early adversity may change the way childhood abuse survivors react to the stress of future adversity, and this is what may be putting them at risk of these health outcomes.” In effect, early trauma may rewire the brain, opening circuits that help survival in the short term but ultimately harm the body they are designed to protect.

The role of epigenetics in disease is as novel and controversial today as germ theory was in John Snow’s London – but local authorities didn’t wait years for confirmation from Louis Pasteur before disabling the notorious Broad Street pump that was the source of the contaminated water. Similarly, Fuller-Thomson is concentrating today not on the basic science but rather on the policy implications of a hidden public health crisis. Her personal goal is to help ensure that all victims of child abuse receive therapy to help them slay the hidden traumas that threaten to darken their future.

Currently, Children’s Aid Societies focus mostly on protecting children from further harm, according to Fuller-Thomson. “So either they remove the child, or they remove the perpetrator, or they do something to keep the child safe,” she says. “And if the child looks like she is functioning – she is making it to school most days, she is not slicing her wrists – that’s it. They’ve done their job to make that child safe from immediate harm, and they go on to the next urgent case. I think this response is inadequate. We have to offer abuse survivors more.”

The good news is that effective treatment is available for the asking. “I’m open to all kinds of therapies, but the evidence is very, very strong for cognitive behavioural therapy [CBT],” Fuller-Thomson says.

Trauma-focused CBT is a relatively short, intensive program that has proven effective for children suffering from the hidden but long-living effects of trauma. Taking place over 12 or 16 weeks, the therapy focuses on correcting the subliminally dysfunctional thoughts that often flow from trauma – especially the propensity of victims to blame themselves for it. “It’s a very simple technique but very powerful for anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder,” Fuller-Thomson says.

“Most children take on some blame for physical or sexual abuse,” she adds. “They may be told by the abuser they’re being punished for bad behaviour, that they deserve this bad treatment. Trauma-focused CBT helps the children grab those thoughts and assess their validity based on other experiences in life.”

The therapy aims to disrupt the intensifying cycles of fear, shame and guilt that so burden young victims of abuse, substituting a more realistic, positive narrative. “At a minimum, we want to give them the skills to know that they don’t deserve abuse,” Fuller-Thomson says. “It gives them the skills to be resilient.”

In light of what she has learned about the dangers of abuse, the researcher has now turned activist, determined to reform what she considers to be an inadequate institutional response to the hidden plague of child abuse. “I even have a date – it’s going to be May 14, 2025,” she says, to mark the 10th anniversary of a talk she gave on the subject. “I want to make sure that, by then, every child in Canada with substantiated abuse gets therapy, whether or not they’re showing symptoms.”

Meanwhile the quest to uncover the social determinants of health continues to beckon. After uncovering the potential source of such grievous harms, Fuller-Thomson has turned her attention to “protective” behaviours and relationships, seeking to understand why some people thrive and others falter. The “burning question” she first confronted as a novice social worker decades ago has lost none of its heat.

“Who gets to be healthy and who doesn’t?” she asks, summarizing what has become her life’s work. Her research so far proposes startling new answers and suggests promising social reforms that could improve the quality of life and well-being of abuse survivors. Marriage and companionship are hugely important in developing what she calls “complete mental health.”

Unconditional love, religion or spirituality and mentorship – “any little bubble of cushioning in a tough world” can help, she says. This summer she received funding to look at how survivors of physical and sexual abuse have achieved and maintained complete mental health. “There are so many people doing well,” she says. “Not a majority, but a substantial minority are thriving.”

With every new study, the search for answers moves steadily upstream, quietly challenging our deepest-seated demons – and helping to rescue their victims one by one.

No Responses to “ The Hidden Epidemic ”

In this interesting article on adverse childhood experience, there is mention of section 43 of the Criminal Code that gives parents and caregivers a defense against assault when corporal punishment is used against children.

To date 50 nations have banned the use of corporal punishment of children. To our shame, Canada is not among them.

Among the 94 calls to action by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, number six is the repeal of section 43. Prime Minister Trudeau has promised to implement all 94. He could start by repealing section 43, bringing Canada in line with countries around the world that recognize the harm done by the use of corporal punishment.

Ruth Miller

BA 1960 UC, MEd 1981

Toronto

Is there a way to join the lobby for change locally and beyond? Please provide a template for change.