When Words Won’t Cooperate

Psychology professor Morgan Barense aims to crack the mystery of non-speaking autism

Isaiah Grewal was in speech classes by the time he was two. He wasn’t saying the words other kids his age were saying, or responding normally when people spoke to him. When publicly funded speech classes didn’t work, his parents got him into special, private classes. Still, he did not speak.

Isaiah was eventually diagnosed with autism. He turned five, he turned 10, and still he was not speaking.

His parents couldn’t tell from his reactions whether he understood what they were saying. He didn’t nod or mirror them. He’d utter sounds, sometimes loudly, but they didn’t seem to be purposeful.

But every once in a while, something strange would happen, like when he’d use foam letters or fridge magnets to spell things out — words like “contents” and “bonus material” that he’d seen when watching a Baby Einstein DVD. “I just felt there was more cognitive ability in him than was being tapped,” his mother, Melody, says.

But how could she know? She and Isaiah’s father, Christian, felt like they’d tried everything. But then, at age 13, Isaiah started working with a communications therapist who taught the family how to use letter boards. These are large boards with the 26 letters of the alphabet printed on them – large enough that even a person with poor motor control can learn, with enormous effort, to point and spell.

It was challenging. Isaiah didn’t have much control over his arms or hands. It took hundreds of hours of training and practice. But eventually, he began telling his parents what he was thinking. One of the first things he spelled out to them was about food, and specifically about restaurant food: “I want to eat off a menu like a normal teen.”

They were stunned. Their son’s diet had been limited to things like fries and nuggets and chocolate. New foods had always upset him, so they’d stopped pushing him to try. But now, using the letter board, Isaiah told them that he’d been upset because he’d wanted to eat the new foods, but he didn’t have the motor control to do it. The same muscles that made it impossible for him to speak, he told them, made it impossible for him to eat those things.

But he wanted to eat them, he insisted, and he wanted them to help him train to do it. Using the letter board, he gave them advice on how. Push it into my mouth again. Chop it into squares. Say chew, chew, chew in a rhythm. For his 18th birthday, Isaiah celebrated at a fancy restaurant, and ordered lobster mac and cheese, from the menu.

About a third of people born with autism are non-speakers, says Morgan Barense, a neuroscientist in the department of psychology at the University of Toronto. People assume, she says, that if a person can’t speak, they must be intellectually impaired.

Barense believes that many autistic people who don’t speak may be hindered not by problems of intellect but motor control. She thinks they may have a condition called apraxia, which is the inability of the body to carry out the motor commands of the brain, a problem sometimes seen after injuries like stroke or head trauma. “Speech is the finest of the fine motor skills,” says Barense. “Think about how you have to move your tongue and your lips in order to execute a sentence. It’s exquisitely controlled.”

People with apraxia, she says, understand what people want of them, want to do it, are physically capable of doing it, but cannot make themselves do it; for whatever reason, their motor systems can’t execute the signals from their brains.

Some non-speakers who have been able to describe what’s going on inside say it’s like being stuck in the body of a drunk toddler, says Barense. They don’t know why they’re suddenly vocalizing Mickey Mouse or talking about Thomas the Tank Engine or running around frantically. They don’t want to be doing these things, they say, but their bodies are like runaway trains.

This was the case with Isaiah, now 22. Once he was able to communicate using the letter board, and later a keyboard, he started describing his inner life. He liked classical music and jazz, he revealed, but not rock or pop. He wanted his shoes to be red.

In an in-person interview I had with Isaiah, I asked what autism felt like to him. Via keyboard, he answered, “Like swimming underwater 24-7 because everything feels hard to control.” I asked what he and his friends talk about when they get together online. “We mostly trash talk,” he responded. Then, later, after I’d stopped laughing, he said, “We just like to hang out in the same space and eat pizza.”

Isaiah has an undergraduate certificate in professional communications from the Harvard Extension School and currently holds a graduate fellowship through Stony Brook University in New York. But other people like him, who haven’t had the benefit of receiving training in how to spell out their thoughts, are being deprived of communication, education and human connection, says Barense: “They’re missing out on that because we are conflating a lack of speech with a lack of intelligence.”

Currently, there are no reliable ways to estimate comprehension, language ability and intellect that don’t require motor output. Vocal speech, sign language, handwriting, typing, pointing — they all involve complex movements that some people simply may not have available to them, says Barense. So, she wants to use neuroimaging to better understand the minds and brains of non-speaking people.

Neuroscientists are well aware that different tasks are handled by different brain regions. With language, one region is believed to specialize in speech production while another is responsible for speech comprehension. Primary motor control is handled elsewhere.

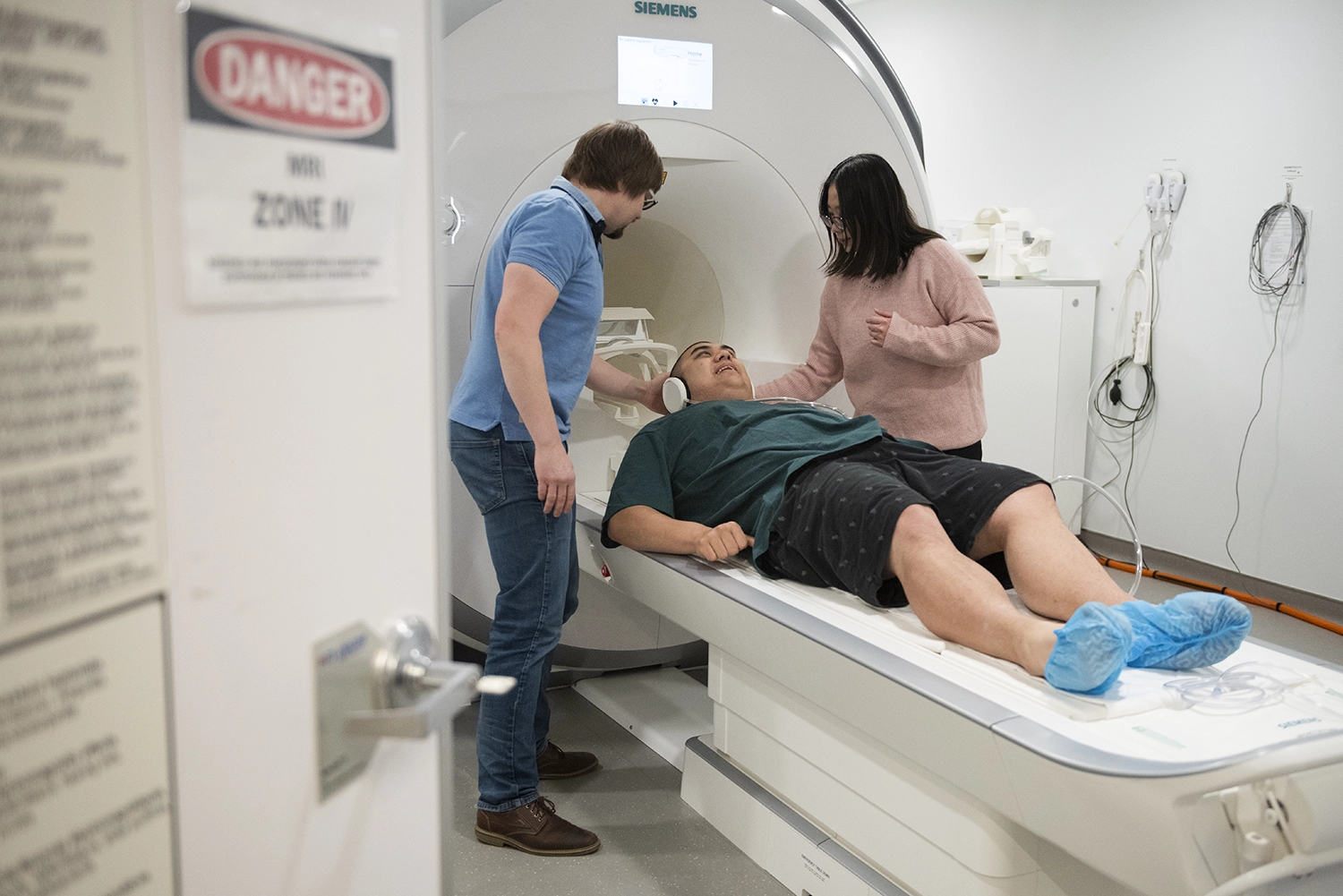

But until now, no one has peered inside the brain of a non-speaking autistic person while they are engaged in cognitively demanding tasks. Barense has so far completed a baseline magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the structure of Isaiah’s brain. Next will come scans of the brain in the process of completing intellectual tasks (known as “functional” MRI, or fMRI).

One of the challenges is that MRI scanning requires a subject to be still. And many autistic people have a lot of uncontrolled movements. Isaiah was able to be still for the 40 minutes of the scan only because of his years of motor training, says Barense. But that may not be so doable for others she’d like to study, so she has applied for a grant to find ways for software to adjust for a subject’s movements.

Barense plans to start with a basic question: what does language look like in someone who is able to understand but can’t speak? How is language represented in their brains? “In these non-speakers who have gained access to fluent communication,” says Barense, “I have a strong prediction that we will find evidence of intact comprehension. I just don’t see how it could be otherwise.” It is completely plausible for one system to not work, she says, while the others are all completely fine.

Using fMRI, she and her team will look for complex patterns of brain activity that reflect high-level comprehension but do not require motor output. For instance, as a person listens to a complicated story, the researchers can track the signal in their brain as that story is unfolding. When there’s a twist in the plot, or a disruption of the narrative, they can see how the brain signal changes in response.

Barense feels it’s important to really listen to what non-speakers are telling us about their experiences and to allow them to inform the science. She had been planning to use movie clips to test this response to plot change, for instance, but Isaiah pointed out that straight audio would work better: when he’s really interested in something, he told her, he closes his eyes.

Barense is also collaborating with a team from Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. Together they will use a recently developed neuroimaging technique to study motor activity in the brains of non-speaking autistic people, including Isaiah. This technique, known as high-density diffuse optical tomography, collects data through sensors on a wearable cap in an unconstrained environment. So, researchers will be able to ask subjects to complete specific motor tasks — tapping a finger, using a spoon, or saying a word aloud — while they watch how the brain is working. Neuroscientists already know what neurotypical brains look like doing these things, but what do brains like Isaiah’s look like?

Down the road, her work could lead to changes in how we educate non-speakers or to new ways of communicating. But for now, she’s focused on simply trying to understand brain organization in this important but poorly understood group. “I think that’s the beauty of basic science,” she says. “You do things, and you don’t know where it’s going to go. I don’t know what we’re going to find, but I know that we need to find it.”

To Isaiah, the work feels urgent. He describes finally getting through to his parents as “freedom from prison.” And the most important thing he wanted people to know while he was trapped in that prison? “That I’m in here.”

Talk Therapy

Isaiah Grewal wrote the poem below for a high school English assignment. He says he wanted to convey that non-speaking people have been wrongfully judged for their inability to speak.

It’s time to talk.

Argh.

Sighhh.

I want my mouth to say what I am thinking,

But it rarely does.

The time teacher told me to read the toddler book

When I was ten

Was no fun.

“The elephant is big,” I said in my head

As my eyes read

And my soul dreaded

What would then always happen next:

“Isaiah, read!” teacher said with a smile.

“Isaiah, read!” my maverick mouth repeated

Over the silence of my mind screaming THE ELEPHANT IS BIG!

Each time this happened, smiley teacher would think she was helping me by explaining more.

The next thirty minutes of her showing me various pictures of other big animals, I spent dreaming of my next trip to Disney.

I didn’t want a master class in pronouncing “ele” that lasted another thirty minutes after the first thirty minutes of the big animal pictures.

I knew if I didn’t speak at least one of the words out loud, I would have to endure this hour repeated again next week.

So I tried to channel all my energy into my throat.

And make my tongue turn or twist to get the words right.

Breath in,

Hold breath and open mouth,

Tongue between teeth,

Breath push out

“the”

Breath in,

Hold breath and open mouth,

Tongue between teeth and roll up,

Breath push out

“ele”

Breath in,

Hold breath and open mouth,

Lips tight together and teeth on lower lip,

Breath push out

“phant”

Breath in,

Hold breath and open mouth,

Teeth slightly apart and tongue against lower teeth,

Breath push out and buzz

“is”

Breath in,

Hold breath and open mouth,

Lips together then apart and tongue flick fast,

Breath push out hard

“big.”

“Good job, Isaiah! High five!” smiley teacher said.

She sat closer to me and turned the page of the toddler book,

“Next week we’ll learn how to read this page,” she said as she pointed.

THE MOUSE IS SMALL! I screamed in my head

Watching the book close in her hands strangling my hopes

As she packed her things to go.

Argh.

Sighhh.

No Responses to “ When Words Won’t Cooperate ”

I'm so happy to see increased understanding of the non-speaking Autistic community! Thank you to Prof. Barense, writer Alison Motluk and, of course, Isaiah Grewal for their commitment to bettering the lives of Autistics!

Please get this article out to The Globe and Mail, Reader’s Digest and other media. All parents of non-speakers know this and the world needs to know, too.

Our grandson, age 7, lives in Toronto, is on the autism spectrum and is primarily non-verbal. With lots of speech therapy, he can say things like, "Thank you, Gramma," although he needs to be prompted to say it. He clearly understands language and can sing the words to all the songs he learns in school, but take away the music and he struggles to speak. Can you help me understand why this is? Motor control doesn't seem to be a problem for him.

Prof. Morgan Barense responds:

@Susan Wallace

Music is one of the best prompts for the motor system. Often the issue is with motor initiation, and putting words to a steady beat can help overcome that hurdle. I am not a clinician, so with that caveat, I would recommend trying neurologic music therapy. (Coincidentally, Michael Thaut, one of the founders of neurologic music therapy, is a professor of music at U of T, with cross-appointments in rehabilitation science and neuroscience.)

Absolutely amazing work. Very moving story. Thank you!

What a powerful story! My husband's son is a 50-year-old non-verbal autistic man. I so want him to speak and be free.

A wonderful narrative that shows what professional help and persistence can produce. What a great moment in the story when Isaiah says he broke the bonds of prison. This provides light for many people who have been diagnosed as non-verbal autistic. Thank you!

This is a fascinating article! My 35-year-old son, who is blind and has autism, is also a non-speaker. His receptive language is good but we feel his quality of life would be so much better if he could tell us more. This study is encouraging.

For those who may be interested, clinical trials for autism/apraxia are occurring at Duke University, under the guidance of Dr. Joanne Kurtzberg, an international expert in pediatric hematology and oncology, pediatric blood and marrow transplantation, cord blood banking and transplantation, and regenerative medicine.

Incredible work! I'm looking forward to more collaboration with school boards to understand student needs and to intervene to support growth. To Prof. Barense and the team: I am in awe of your collective work and what programming changes this research can bring to support student achievement.

My son also spells with Isaiah's therapist; it brought stability to his mental well-being and the agency he was desperately seeking as a teenager. But the method the therapist uses isn't widely accepted -- partly because of resistance within the speech therapy professional organizations, where the belief is that prompts (used to guide the child) interfere with independent thought. Yet children get prompts all the time from their parents growing up. Like training wheels, prompts are a natural way of learning until the child is able to manage independently.

Thank you to Isaiah, a beautiful young man; to his incredible mom for finding this under-the-radar method; to Prof. Barense for her research and for having the compassion to see beyond stereotypes; and to Alison Motluk for a well-researched and inspiring article!

Powerful and incredibly moving. Thank you for this article.

Very solid piece. I'm so glad the writer, Alison Motluk, got to speak with Isaiah Grewal. There's so much yet to learn about how brains work (and almost-work).

My 35-year-old son is also non-verbal and struggles with comprehension. He uses a picture-based iPod for communication but as a young boy seemed to indicate that he would like to talk. He lacks confidence in his communication, which made typing without assistance almost impossible. I would love for him to be able to communicate his thoughts and feelings.

This is the most interesting and amazing story I have read in University of Toronto Magazine. I am in tears. Thank you for this article. Incredible work!

Wonderful article! Thank you to Prof. Barense, writer Alison Motluk and, of course, Isaiah Grewal for giving us this insight. I wish Isaiah all the best for his future. I have a nine-year-old autistic girl. She was non-verbal till she was three-and-a-half, would only communicate through sounds and hand gestures. After numerous sessions of speech therapy and constant encouragement at home, she is able to speak now. Her words are still all over the place, but we are all working hard. Music and art have been a big help for calming her. There are a lot of resources for autism, but I am saddened as a parent that the wait-times to access these resources is causing kids on the spectrum to lose valuable time.

Thank you to Prof. Morgan Barense and Isaiah Grewal for sharing this story and for the great work that is being developed for non-speaking people on the autism spectrum. Very moving!

Thank you for the incredible work, Isaiah, Dr. Barense and her research team, and writer Alison Motluk! As a family member of Autistic cousins, this greatly help me to understand them better. Isaiah's poem also sums up the study as well.

Have you seen this work by Adam Wolfond? It’s also important to understand the way that language is part of autistic proprioception. It entails how autistic perception is so saturated in the teeming welter of the world, and how neurotypical perception - that is also taught - cuts the field; the separation between body and world doesn’t exist for many autistic people and we also need to value that! Congrats to Isaiah for participating in this study. Here is the link of the most recent video/sound installation by Wolfond that recently closed at Koffler Arts: https://youtu.be/Uk7w8JJnxNg?si=odyVf6l-hezZEn6_

This is so so wonderful. My son is 21 and uses a letter board. How do we get professionals to understand?

It’s wonderful to see new research validating the pioneering work of Dr. Anne Donnellan, Martha Leary, David Hill, and others — published decades ago — highlighting that autism is fundamentally a movement disorder rather than a cognitive deficit.

Isaiah’s story is a testament to the reality that many non-speaking autistic individuals are highly intelligent but struggle with motor control, not comprehension. This reinforces the urgent need for more widespread access to alternative communication methods and a shift in how we educate and support non-speaking, neurodivergent individuals.

It is wonderful to see Isaiah Grewal front and centre in this. His voice and the voice of so many Non-Speakers and multi-modal communicators is where the focus must be. Isaiah, thank you for continuing to pave the way. It brought me sincerest Autistic joy to see your name come across my feed again!

I have shared Listen, a short film about the importance of listening to Non-Speakers, with staff and colleagues so many times. I know how meaningful the film was and is, right across the world and how much of an impact you and fellow non-speakers are having on shifting how the world sees and understands Autistic ways of being!

Love, respect and solidarity to Isaiah, to the writer, Alison Motluk, and to professor Morgan Barense for this important work. I shall be watching very closely as I too am researching the gaps in school assessment practices and processes, which continue to underestimate Non-Speakers.

Kudos to Prof. Morgan Barense for her research into helping Isaiah Grewal and others like him find their voice. For him to be able to communicate is a wonderful accomplishment. It was moving to read about.

I would suggest the professor also look into disassociation. My son is fully open on letterboard and can type on an iPhone and iPad. He must contend with another distinct, more infantile personality who has its own preferences and retains majority motor control. Via typing, his executive is able to speak on their behalf. Typing helps integrate the mind bit by bit, but we are also looking into low-dose naltrexone and Riluzole to address the disassociation. I know it’s early days and this may seem tangential, but my son and I believe many other kids share this underconnectivity. I’ve read research of another team showing intense prefrontal cortex activity surrounded by dark everywhere else. My son responds to the supplementation we use to address his underconnectivity. It would be good if this could be investigated as well.

Very interesting! I am special ed. high school teacher. The article mentions that one-third of children with autism are non-verbal; at our school it's much higher than that. I've been exploring Gestalt Language processing and your article complements ideas I've been having for a while.

We tend to dismiss verbal communication and focus on receptive language. I've been using keyboarding for a few years now and seeing some anecdotal improvement in concentration and keyboard skills. The keyboard is text to voice, so the student hears what they're typing. By the time the students are in high school the opportunity for the intense training the article mentions has been missed. But other options can be practiced at home.

I want to thank Alison Motluck for this wonderful story! It brought tears of happiness to my eyes for the future of the non-speaking Autistics community and my granddaughter. To finally prove that they are bright individuals trapped by a motor dysfunction that can be treated by practicing motor control techniques through spelling and typing independently and being able to express themselves. My gratitude to Professor Barense for her outstanding work and dedication to this community!

Thank you for pursuing this important research and finally allowing the voices of non-speakers to influence the methodology, which has been flawed for decades. We need more scientists to challenge popular beliefs and change the conversation around non-speakers.

My son was 18 days old when he was diagnosed with congenital heart disease and had to undergo open heart surgeries. By age two, he was not speaking and I started to get worried. In pre-kindergarten, he was diagnosed with Autism. We put him in speech therapy and behaviour programs. When he was in Grade 8, COVID shut everything down. Virtual classes were not suitable for him, so he started home schooling. There have been many ups and downs but my perspective is to consistently try my best.

My son is now 18. I came to the U of T website to get information for him and was so glad to see the story of this young man who is discovering his strengths. I can feel how his parents are happy to see his progress. Keep it up!