Tom Chau helps the silent speak. Working with an almost-telepathic technology known as a brain-computer interface, Chau and his lab help people with no speech and limited or no control of their limbs articulate simple words such as “yes” and “no” using only their thoughts. Eventually, people may communicate more complex answers just by thinking them.

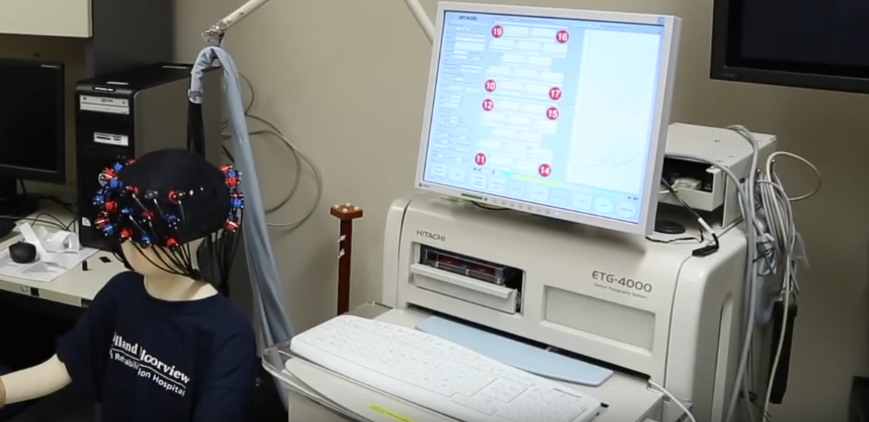

For now, the technology requires the subject to wear a cap covered with wires and electrodes (or with light sensors and emitters) hooked up to a computer. When the person speaks a word such as “yes” silently in their head, the computer recognizes certain brain patterns associated with it. One form of the brain-computer interface can even tell if you’re singing a song to yourself – and if it evokes a positive or negative emotion.

Chau, a professor at U of T’s Institute of Biomaterials and Biomedical Engineering, has been studying brain-computer interfaces for more than a decade and has helped make them more intuitive for users. A key discovery enabled clients to communicate by changing oxygenation levels in their brain.

In one experiment, subjects were given a map of the prefrontal cortex region of the brain and taught to change its colour from red to blue and vice versa, where blue signified less oxygen and red indicated more. The map served to guide users in their quest to modify their brain activity and achieve the desired colour. “By the end of the training, these people were able to play a simple video game with their minds,” says Chau, who is also vice-president, research, and a senior scientist at Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital.

Even a brain that’s not thinking of a song or a specific word is a very active place. So one of Chau’s biggest challenges was to distinguish the signals of a “brain at rest” from one that was trying to send a message. It took several years, but his team was able to create a kind of “profile” of the resting brain. Now they can tell when their subjects are simply tuned out. “That was a big breakthrough,” says Chau.

Another challenge is that each person’s brain patterns are distinct – my “yes” is not the same as your “yes” – so the machines have to be trained to understand individuals, and this can be a laborious process. Chau is looking at ways to simplify it by having clients listen to a stream of words, all with distinctly different sounds; he then uses the machine to create what is essentially a personal dictionary of the brain’s reactions. (Listening to a word activates the same part of the brain as silently saying it.)

Chau’s research has focused on applications for children, but the technology could help a variety of people – including individuals with multiple sclerosis or who have suffered a stroke or spinal cord injury.

At the moment, the technology exists only in the lab. But corporations are keen to use brain-computer interfaces in gaming, driving and entertainment, and Chau thinks it’s just a matter of time before his version goes mobile. “I think the day when we’ll be sending kids home with their own headsets is not that far away. I’d say within the decade, maybe sooner.”

Recent Posts

People Worry That AI Will Replace Workers. But It Could Make Some More Productive

These scholars say artificial intelligence could help reduce income inequality

A Sentinel for Global Health

AI is promising a better – and faster – way to monitor the world for emerging medical threats

The Age of Deception

AI is generating a disinformation arms race. The window to stop it may be closing