Two University of Toronto engineering graduates have found that creating stronger computer security can be as simple as listening to your heart.

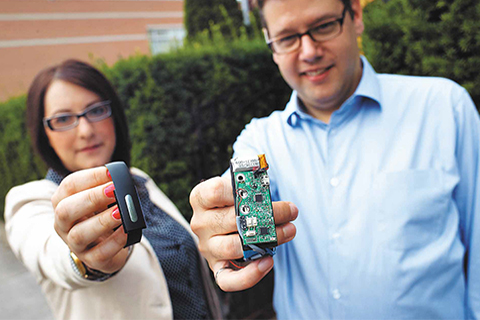

Foteini Agrafioti and Karl Martin have invented the Nymi wristband – the world’s first wearable security device that detects a person’s unique cardiac rhythm to authenticate their identity and allow access to their digital devices. They say the wristband is more convenient and secure than passwords, keys and swipe cards. They also believe it is superior to other biometric solutions, such as fingerprint, iris and face recognition, which require careful body positioning for an accurate scan, and which can be easier to imitate than the peaks and valleys of one’s cardiac signal. Since its launch this past fall, their technology has generated significant buzz among security companies, tech developers and investors.

Activating the Nymi requires touching its electrocardiogram sensor so it can identify your cardiac rhythm, which varies in each person according to factors such as the heart muscle’s size and its location in the thorax. The technology works even when your heartbeat fluctuates from exercise or stress, and it can learn a new heart rhythm after a heart attack or other cardiac event. Agrafioti (MASc 2008, PhD 2010) says that it is extremely difficult to spoof the system with a fake heartbeat.

Once authenticated, the system communicates via Bluetooth to the Nymi software app operating on a designated device. While wearing the wristband, you can seamlessly unlock and use your smartphone, tablet or computer; removing the wristband automatically locks linked devices. Future versions may unlock cars or homes, facilitate online banking, track fitness activity and control smart home appliances.

The algorithm for the wristband’s HeartID software evolved from Agrafioti’s doctoral research in electrical and computer engineering. Martin (BASc 2001, MASc 2003, PhD 2011) was exploring how to enhance the privacy of biometric data. Their complementary research interests led them to become business partners in spring 2011, when they co-founded Bionym.

Bionym is a good example of a U of T startup that benefited from the university’s flourishing entrepreneurial ecosystem. The company’s first office was at U of T’s Banting and Best Centre for Innovation and Entrepreneurship. The university’s Innovations and Partnerships Office assisted with filing a patent, advised on commercialization options and helped write grant applications. The company secured about $300,000 in government grants, which it used to hire staff and continue research.

In fall 2012, Rotman School of Management’s Creative Destruction Lab, a year-long business accelerator program for startups, offered Bionym a spot. The program provided connections to business faculty, MBA students and successful entrepreneurs, and free legal and accounting services, among other things. Bionym also got help attracting $1.4 million in seed money, which it used to rent an office in downtown Toronto, hire more staff, purchase equipment, develop a prototype and create a website.

Working in Bionym’s favour are two fastgrowing markets: wearable technology and biometrics, the latter of which got a boost after Apple included a fingerprint sensor in its latest iPhone. Since September, Bionym has sold about 7,000 units of the $79 Nymi (with an early 2014 shipping date). It has also attracted much interest from software developers with application ideas, and from companies – including every major smartphone manufacturer – about licensing or integrating the technology.

“We need to prove our identities every day to the world,” says Agrafioti, now Bionym’s chief technology officer. “This is a way to do that efficiently and securely.”

Recent Posts

People Worry That AI Will Replace Workers. But It Could Make Some More Productive

These scholars say artificial intelligence could help reduce income inequality

A Sentinel for Global Health

AI is promising a better – and faster – way to monitor the world for emerging medical threats

The Age of Deception

AI is generating a disinformation arms race. The window to stop it may be closing