The Limits of AI

As artificial intelligence advances, humans need to pay closer attention to what it can and can’t do Read More

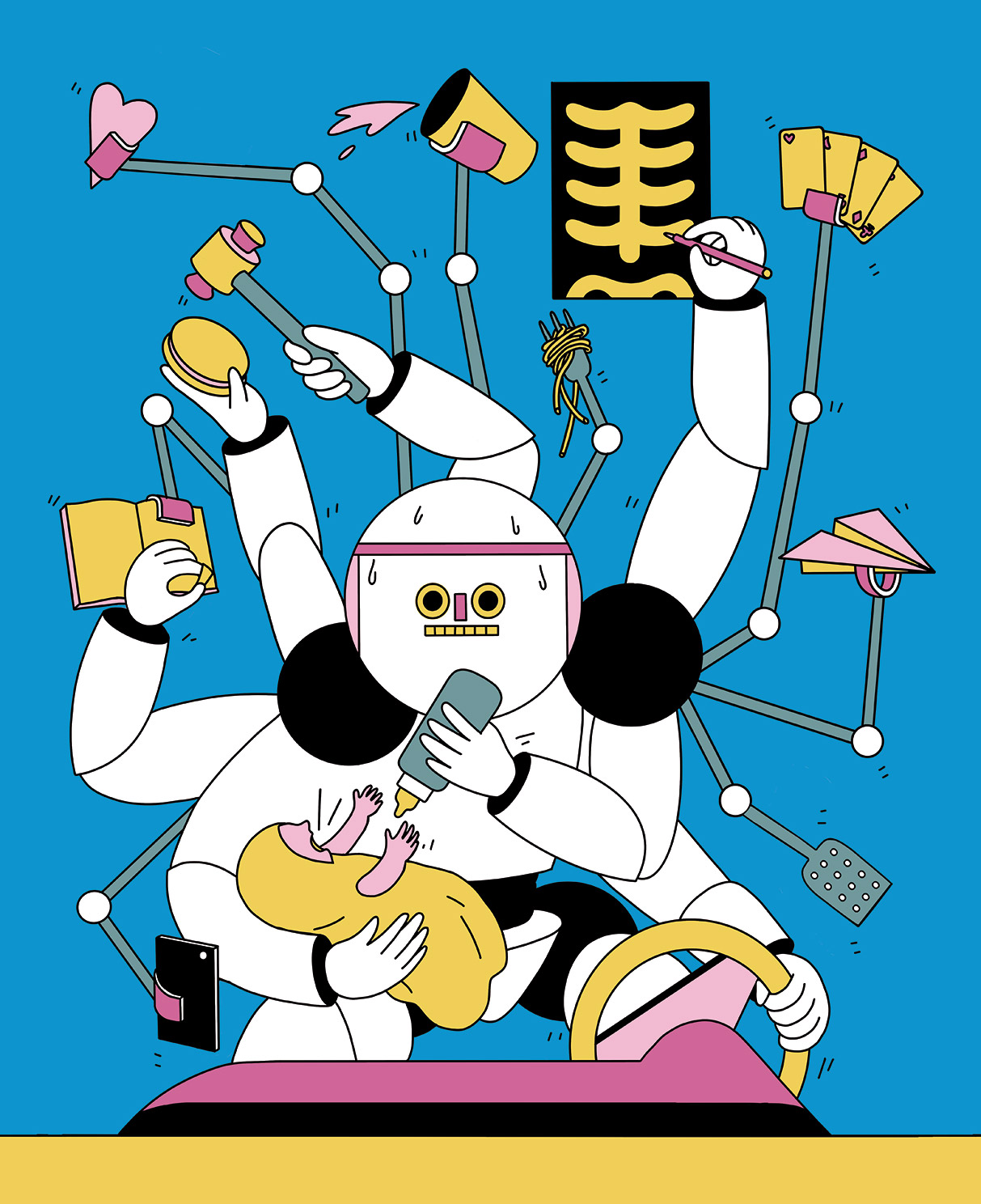

Artificial intelligence (AI) continues to make deep inroads into all aspects of society – from reading X-rays to driving cars. But is our ability to assess the limits of AI keeping up? Are there areas where we should not deploy AI to assist us?

These are the kinds of questions that interest Brian Cantwell Smith, the new Reid Hoffman Chair in Artificial Intelligence and the Human at U of T’s Faculty of Information, whose goal will be to shed light on how AI is affecting humanity. The chair was created in 2018 through a $2.45-million gift from Reid Hoffman, co-founder and former chairman of LinkedIn.

Smith spoke with us recently about where AI is headed. Hoffman annotated the interview with his own perspective.

Is it fair to say that it’s not just the public who have misconceptions about AI, but scientists and experts as well?

I think all of us need a deeper appreciation of the stuff and substance of human thinking and intelligence. I want to bring attention to the gravity and the stakes of the development of AI and to the incredible accomplishment humans have wrought, over millennia, in developing our ability to be intelligent in the ways that we are.

I’m not thinking of something so specific as putting a man on the moon, but, for example, what it means to be a fair and honest judge in a court of law, or to inspire children through education to stand witness to what matters in the world, or to convey the message through great literature that life is worthwhile to the extent that one commits to something larger than oneself.

These accomplishments remain a long, long way in front of anything the technical branches of AI have even taken stock of and envisioned, let alone accomplished.

People seem alarmed when they talk about AI. Is this justified?

I think there are two parts to the general alarm people are feeling. One is that AI is going to be bad – it’s going to enslave us, it’s going to divert all our resources, we’re going to lose control. This is a late-night horror movie kind of worry.

The other is that AI’s going to best us in all sorts of ways, take all of our jobs and replace everything that’s special about us. This doesn’t require AI to be evil or bad, but it is still a threat in that it challenges our uniqueness. I don’t think that second worry is entirely empty.

Could you elaborate on this second worry – that AI will become better than us at many tasks?

My overall concern has to do with whether we are up to understanding, realistically and without alarm, what these systems are genuinely capable of, on the one hand, and what they are not authentically capable of, on the other – even if they can superficially simulate it. I am concerned about whether we will be able to determine those things – and orchestrate our lives, our governments, our societies and our ethics in ways that accommodate these developments appropriately.

This leads to a bunch of specific worries. One is that we will overestimate the capacity of AI, outsourcing to machines tasks that actually require much deeper human judgment than machines are capable of. Another is that we will tragically reduce our understanding of what a task is or requires (such as teaching children or providing medical guidance) to something that machines can do. Rather than asking whether machines can meet an appropriate bar, we will lower the bar, redefining the task to be something they can do. A third and related worry, which troubles me a lot, is that people will start acting like machines. I feel as if we can already see this happening. Students, for example, often ask how many references they need to get an A on a paper. Faculty going up for tenure are worried about how many citations they’ve received. We can’t quantify importance. If we reduce human intelligence to counts – to a measure of how many questions you get right – we’re lost.

What do you think is missing from discussions about AI?

We’re seeing extreme views in both directions – doomsayers and triumphalists. Either it’s all going to be terrible or it’s all going to be wonderful. Very rarely do such wholesale proclamations prove to be the deepest and most enduring views. 1

I’m particularly concerned that many of the people who have the deepest understanding of what matters about people and the human condition have only a shallow understanding of artificial intelligence and its power. And vice versa: Those who have a deep understanding of the technology often have a shallow understanding of the human condition. What we need is a deep comprehension of both. It’s as if we are at (0,1) and (1,0) on a graph, when we need to be at (1,1).2

Ideally, how would you like the discussion to proceed?

We need to set aside the whole “people versus machines” dialectic, and figure out what skills particular tasks require and what combinations of people and machines can best provide those skills. Calculate pi to a million decimals? Clearly a machine. Teach ethics to schoolchildren? Obviously a person. Read an X-ray? Tricky. It may soon be that the best strategy will be for an AI to do the initial classification and pattern recognition on the image, but for a seasoned physician to interpret its consequences for a lived life and recommend a compassionate treatment strategy. As machines start to be able to do certain things better, we should include more of them appropriately in the mix.3

Let’s leave to the machines what they can do best, set those things behind us and raise the standard on the parts that require people – the parts that require humanity, depth, justice and generosity. 4

No Responses to “ The Limits of AI ”

The best examples of artificial intelligence today are only examples of complex automation. There is no intelligence in those systems -- not even in the software that plays Jeopardy. Today, we don't know how consciousness functions in the brain. In the future, when there is an adequate theory of where intelligence originates in the brain and how it functions then there might be some dim hope of implementing an actual artificial intelligence system.

More than 30 years ago, when I started a firm that required "people skills" such as compassion, integrity and value-based vision, many people came to me and described what technology could do for the company. Some ideas were appropriate and helpful. Back then, I thought of it as "high touch vs high tech." AI has its place and we need it to advance our work and our lives. But we also need "high touch." Losing sight of the value of people has harmful everyday effects, and they concern me.

Thank you for this article. It gave an overview of the pros and cons of artificial intelligence and answered questions about AI very well.

There is a concern about AI replacing jobs in every field from teaching to medicine, finance, the military, mining and the service sector. What will happen to people who make pizza for a living if an AI can make 50 pizzas an hour? What will happen to disabled and older workers who may find it difficult to learn how to use AI in their jobs? Measures of success at work should not be just quantitative, but should include values, purpose and culture.

While not detracting from the other comments on this article, I simply point out the lack of an acknowledged philosophic approach to this issue. To my mind, initially a sound philosophic understanding of what it means to be human -- from the perspectives of Western and Eastern cultures -- is required.